How can lawyers find flow?

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/ABA Journal

The pandemic has disrupted our work lives in many ways, but dare I say that some interventions have been positive?

Of course, working at home, juggling stressful job responsibilities with family life and adjusting to different technology all have, at times, left us feeling like we are drinking from a fire hose.

But let’s take a moment to survey the positive work moments we have experienced over the past nine months. Do you remember a stint of researching or writing in which the world seemed to disappear and you became happily lost in your project? Do you recall an instant in which you were exercising and a creative solution to a legal problem popped into your head? Do you recollect a period in which you enjoyed working in an unusual location or at an odd time of day and you hit a surprising new stride of productivity?

The pandemic prompts us to set aside business-as-usual practices and consider: What are the optimal working conditions that help us achieve the state that psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow”?

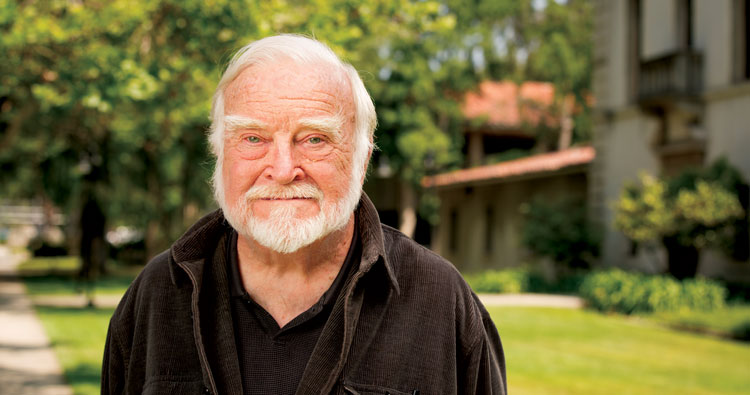

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defines flow as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter.” Photo courtesy of Claremmont Graduate University

Csikszentmihalyi defines flow as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter.” He says we can achieve flow when “our body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

Flow is not just for elite athletes, creative singer-songwriters or influential artists. We, as members of the legal profession, can also achieve flow. And it’s a triumphant feeling when we do.

How lawyers can find flow

Have you ever been knee-deep in drafting a contract or a brief and been so engrossed in the writing project that you forget what time it is? The pandemic temporarily disappears from your psyche, you hit a groove and the words tumble into the right order on the page. And when you emerge from the writing bubble, you feel like a gladiator. That’s flow.

We don’t need to wait for external forces such as a lightning bolt of inspiration, the invention of a vaccine or the arrival of a long weekend to facilitate flow in our lives. We simply need to understand what flow is and how it works. Then we start noticing situations in which we feel like we are in our “flow zone.” Ultimately, we can cultivate circumstances in which we enter a state of flow more often.

Csikszentmihalyi says flow requires a proper balance between challenge and skill. The project or task needs to be sufficiently difficult, prompting us to stretch our intellectual muscles to achieve its attendant goals, but it can’t be impossible or unrealistic. If we lack the concrete skills to execute the activity, we won’t achieve flow; high challenges met with insufficient skills foster anxiety. In contrast, if we have the skills but the project is too easy, we’ll cultivate boredom or apathy.

Csikszentmihalyi emphasizes that flow is possible when our brains and bodies have the freedom to invest full attention in achieving the task’s purpose, because we are not grappling with internal disorder or defending against threats.

To learn how to facilitate a flow state for ourselves and others, let’s ask ourselves: Do I feel internal disorder right now? Why? Am I sensing a threat? From whom or what? Is this challenge impossible or unrealistic, or is the end goal reachable? Do I have the skill set to execute this task?

Let’s consider this calibration, for example, when assigning projects to junior attorneys. They can achieve flow if the assignment is difficult but not impossible—substantively, logistically or deadline-wise—and they have had proper training to perform the task. Conversely, if we pile work onto junior lawyers that has unattainable end goals or deadlines or we expect them to magically complete the work without sufficient training or experience, a flow state is impossible.

If we are responsible for delegating work to others in our organization, are we setting up those employees for success? If not, can we provide better training? Is it possible for us to enhance productivity, motivation and happiness for individuals and within institutions by reorganizing and restructuring work lives to foster flow? It’s worth a try.

I most often achieve flow when tackling a writing project. I remember many episodes in my law firm life in which I would finally look up from my computer after hours of crafting a complicated brief. I’d feel dizzy and disoriented yet gratified and almost euphoric. Grumpy law firm partners and snippy opposing counsel temporarily ceased to exist. The challenge-skill balance enabled flow. The tricky task of articulating logical and persuasive arguments inspired rather than intimidated me. I had developed sufficient writing chops to rise to the challenge if my deadline was reasonable and the task did not feel impossible or unrealistic. Most often, this flow state occurred at odd hours as I sat in comfortable sweatpants on my couch at home, surrounded by printouts of cases and client fact documents.

As an introvert, my concentration is easily derailed by the normal office soundtrack of phones ringing, colleagues chatting and doors opening; I rarely hit my peak flow state at my office desk. Over the past year, the opportunity to set up my work-at-home life during the pandemic has fostered rather than thwarted flow.

Tools for success

Csikszentmihalyi’s advised balance between challenge and skill reminds me of another approach to well-being called self-determination theory, developed by psychologists Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan. Deci and Ryan say human motivation derives from three psychological needs:

- Autonomy: having a sense of control over our lives and being able to act in a way that dovetails with our individual interests, values and beliefs.

- Competence: feeling capable of handling daily interactions, experiences, tasks and responsibilities.

- Relatedness: connecting with other people.

In assessing how we can motivate ourselves and others—especially as the pandemic trudges on—we should consider whether and how we are cultivating autonomy, a sense of competence and relatedness.

When I was a law firm associate, it wasn’t the workload that fueled my anxiety; in fact, I loved the substantive work. It was the complete absence of autonomy. I never knew if the senior partner was going to saunter into my office with another assignment one minute before I finally planned to go home for the night, or if he would decide—on a Friday evening—that a memorandum needed to be written by Monday or if he would assign me a new case on the eve of a long-awaited vacation planned with other people who depended on me. My life was controlled—or at least I believed it was—by the whims of the partners, opposing counsel or clients. Gripped with self-doubt, I also grappled with the fear that I lacked the competence to handle unfamiliar arenas. A “never show fear, never show weakness” ethos often stands in the way of lawyers’ ability to ask for guidance or additional training.

As we hopefully inch toward emerging from this pandemic, let’s consider how we can enhance motivational autonomy. We will not sacrifice rigor, high standards or billable hours by affording employees a sense of control over their lives in a world that feels completely out of control.

If an individual is more likely to achieve a flow state by working from home, let’s figure out a way to make that happen. If an employee needs to feel able to step away from email and electronic notifications on a reasonable basis, let’s make that happen. Further, as we hire new attorneys and staff members (who already are living and existing in a protracted state of unease), let’s provide adequate training on new tasks to build a sense of competence. As we edge across the finish line of a traumatic year and start a fresh one, let’s generate a sense of relatedness and belonging.

We’ve all done the work to become legal professionals. We’ve sheltered in place, adjusted our daily interactions, adapted to new technology and endured grief, loss and staggering bewilderment over the past year. We are in this together. Let’s reach out and make sure all members of our profession know they deserve to be here. Now more than ever. Let’s nurture individual and collective flow states and define this next year by good health, hope for the future and awe at what we survived and achieved together.

This story was originally published in the Dec/Jan 2020-21 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Finding Your ‘Flow’: From drinking from a fire hose to achieving our peak state.”

Heidi K. Brown is a professor of law and director of legal writing at Brooklyn Law School. She is the author of The Introverted Lawyer: A Seven-Step Journey Toward Authentically Empowered Advocacy (ABA 2017) and Untangling Fear in Lawyering: A Four-Step Journey Toward Powerful Advocacy (ABA 2019).