Foreclosure firm goes statistical to improve speed and quality

Matt Hunoval: “I can see the lightbulb moment where the client or potential client says, ‘Oh my God, here’s a lawyer who actually gets it.’ ” Photo by Randy Piland.

Matt Hunoval felt bored to his marrow as a big-firm associate in the nation’s No. 2 banking capital, Charlotte, N.C.—doing due diligence, preparing ancillary documents and performing other drudge work for billion-dollar M&A deals. So despite making more money than he figured a fifth-year associate is worth, he left in 2009 to do what seemed even more perfunctory—handling flat-fee residential foreclosures by himself.

He had certainly honed the skills for exacting tasks at his old employer, Moore & Van Allen, and now pored over every line of the documents in his new field: affidavit of default, substitution of trustee, trustee’s deed, deed of trust and notice of hearing. The work excited him.

But Hunoval’s story is a bit richer than the simple irony of walking away from comfortable monotony to take a chance on even greater tedium with decidedly less glamour. And he doesn’t shy away from criticism of his chosen practice and the checkered history of foreclosures.

The industry is ridding itself of the scandalous, robo-signing foreclosure mills that faked documents to prop up questionable mortgages, though court battles continue over whether many of the tens of millions of mortgages bundled and securitized for sale to investors during the housing boom-and-bubble still have questionable chains of ownership.

But for Hunoval there is the legitimate and necessary business of foreclosure that someone is going to do, and he wants to be known for the best way to make the process swift and true. If he does it well, he figures, some who might otherwise be foreclosed on because of an occasional mistake in the vortex of volume could be saved by his attention to detail.

“Even before you start to tell the story, the narrative is set and we’re the guy in the black hat riding in on a black horse,” says Hunoval, who gets referrals from half a dozen clients, including mortgage servicers, banks and small hedge funds. “But if we reduce error rates, it helps our clients, who don’t want to foreclose when it’s not merited. They want to service the loan. And that’s good for the debtor.”

For the first years, he had only one major client, a “whale” as he calls one of the top 10 mortgage servicers in the nation, in addition to some “bluefish” and “minnows.” More recently Hunoval landed two more whales.

Hunoval’s firm has grown quickly to 70 employees—nine of them carefully picked lawyers, some with particularly beneficial backgrounds and experience for the boss’s vision. Those numbers include a cushion for handling the new, big clients, and he estimates the staff could grow to 90 by the end of the year.

While he hasn’t gotten much notice in the legal profession, Hunoval’s approach is attracting the studied gaze of the business world for the programmatic, systematic efficiencies that, as he puts it, he’s building into his firm’s DNA from the lowliest clerk to his highest-paid lawyer.

Photo of Kevin Divine by Randy Piland.

FASTER, CLEANER

In January, for instance, Hunoval’s chief information officer, Kevin Divine, attended the noted PEX Week (short for Process Excellence) annual gathering in Orlando, Fla., to present a case study of the firm’s rapid achievements in running a foreclosure firm faster with fewer mistakes.

A nugget: In the firm’s first concentrated effort at new efficiencies that began in January 2013, it achieved an impressive 88 percent decrease in the number of days it takes from the time a North Carolina foreclosure referral arrives until it files the notice of hearing that begins the process in the courts. An average of 69 days was whittled to just eight.

Divine’s presentation was bracketed by speeches by the likes of DuPont, Google AdWords, Coca-Cola, ConocoPhillips, State Farm and Lilly Research Laboratories—entities with names far more recognizable than that of the Hunoval Law Firm. They all talked about change in the way their work is done.

“But this is not about change in how we practice law,” says Hunoval, 40. “It’s about law practice management, improving the business side—an idea that is changing how law firms can be run.”

Indeed, you’re more likely to hear him utter terms like low-end functionality and scalability rather than those like interlocutory or purchase agreement.

“To the extent we are ‘a mill,’ then we can use a very successful, widely adopted management tool from the manufacturing realm,” Hunoval says.

That tool would be LSS, for Lean Six Sigma.

The data- and metric-driven approach to process improvement first developed by Toyota took hold in the U.S. with Motorola’s adoption of Six Sigma for manufacturing in the early 1980s. It is best known for General Electric’s then-chairman Jack Welch embracing it as a main business strategy in 1995. (Divine earned his LSS black belt, a certification of expertise in the methodology, at GE in 2000, and he was on its eight-person team outsourced to run Xerox’s notoriously chaotic back-office invoicing, billing and collections in 2003, a significant factor in pulling Xerox out of a sinkhole of debt.)

Six Sigma concerns quality control for fewer defects or mistakes. Lean is a methodology for finding and eliminating wasted effort. In recent years the Lean aspect has regained its earlier luster as various service industries have adopted what first was a manufacturing practice for streamlining processes.

Hunoval’s clients are primarily large financial institutions that—like others in manufacturing, construction, engineering and pharmaceuticals—adopted some version of Six Sigma 20 or more years ago. It’s in their cultures.

“When they hear us speaking that same language,” Hunoval says, “I can see the lightbulb moment where the client or potential client says, “Oh my god, here’s a lawyer who actually gets it.”

Photo of Cara Clausen, director of legal operations, by Randy Piland.

HIGH ACHIEVER

Though Hunoval started out as a big-firm lawyer, he doesn’t come across like one. He does, though, have the bona fides: just in case Wake Forest University School of Law’s tie for No. 36 in the U.S. News rankings in 2003 wasn’t enough for an initial career boost, he went straight to the New York University School of Law for an LLM before entering practice. That diploma is, he says, “the most expensive piece of art on my wall.”

Hunoval was initially drawn to transactional work, which belied his roiling energy, presence and manner, more like those of a bare-knuckled litigator who doesn’t want to settle. Besides being blunt-spoken with often earthy phraseology, he’s 6-foot-2, beefy and cut like a linebacker, having played football in high school and then rugby until he was 32, when the physical recovery period between weekly matches itself grew to a week. He is given to three-piece suits and his trademark Lucchese cowboy boots, handmade in Texas.

The seemingly unavoidable swagger is muted. His aggressive agility in growing a business is not.

It appeared likely in the economic straits of 2009 that the spate of foreclosures would be a geyser without the on-and-off intervals. That was in the air when Hunoval got a call in March 2009 from a close friend he roomed with in their fraternity house at Davidson College, someone who worked for a nationwide mortgage servicing company. The friend was having problems with some law firms handling foreclosures in the Carolinas and asked whether Hunoval was interested in getting into that practice.

“He said, ‘Just get a paralegal who’s been in this for eight to 10 years and you’ll learn it quickly,’ ” recalls Hunoval, sitting in his office decorated with furniture as oddly fashioned as it is distinctive: two desks, a bookshelf and club chairs made of polished aluminum riveted together in a patchwork reminiscent of WWII fighter planes—scrapes, dings and all.

By that summer he and paralegal Cara Clausen (now the firm’s director of legal operations) got a dozen or so foreclosure referrals, and he applied his M&A-acquired attention to detail.

“We were making almost no mistakes, and I was personally looking at every line of every document we turned out, with some very favorable results for clients,” Hunoval says. “Once the mortgage servicer decides to foreclose, time is everything and mistakes devour time.”

Photo by Randy Piland

AN ALL-LEAN STAFF

As Hunoval grew his own business from scratch, it was perhaps the most significant in a series of bold moves when he had, as he puts it in business-speak, “25 W-2s” working for him and decided to have every one of them, from the lowliest clerk to his highest-paid lawyer, trained in LSS for process improvement.

He wanted to separate himself from the small pack of law firms handling foreclosures in North Carolina, with an eye to South Carolina and more. He’s still probably No. 4 in volume but believes his growth curve will continue, and the firm is diversifying into other kinds of work.

Hunoval had learned of LSS from a personal friend, Ted Theodoropoulos, whose company Acrowire helped develop the law firm’s IT system—and who also happens to be an LSS black belt who works with law firms on process improvement.

“With such a highly commoditized practice like default service, Lean Six Sigma seemed a perfect match—except to a lot of law firms,” says Theodoropoulos, who did process management for Bank of America before going out on his own. “Matt wasn’t tied up by having done things a certain way for so long that he couldn’t imagine a better way. He got it.”

Divine was with Acrowire and soon embedded in Hunoval’s offices, eventually becoming another of its W-2s.

Then Hunoval made another of his typical leaps. He approached professors at the Center for Lean Logistics and Engineered Systems at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and sold them on the idea of the legal profession as new territory for them. Lean training focuses on process efficiency more than the curing of defects addressed by Six Sigma.

“I appealed to their self-interest with a chance to change an entire industry that involves billions of dollars,” Hunoval says. Beginning in late 2012, Hunoval has sent six to seven staffers at a time to the school for Lean training based on real projects being developed for the firm.

They attend UNCC for full days of class each Friday for five weeks, earning green belt certifications. Typically, a green belt has gained a practical understanding of the methods for analyzing processes and using certain tools to improve them; black belts can fully design, implement and supervise projects in which those skills are applied, as well as teach and mentor.

By the end of 2013 a third of the staff had completed the program, and a full 70 percent is expected to by the end of 2014. The first project addressed the overly long process for a notice of hearing and achieved the impressive 88 percent timeline improvement.

Ertunga Ozelkan: “It helps that he’s doing this as a startup, when his firm is young.” Photo by Randy Piland.

“It helps that he’s doing this as a startup, when his firm is young,” says Ertunga Ozelkan, associate director of the Lean logistics center, who co-authored a scholarly paper on the firm’s efforts presented in September in Atlanta at the Institute of Industrial Engineers’ annual Engineering Lean & Six Sigma Conference. It won second place in competition among 50 entries.

But it’s not that Lean or LSS can’t be adopted in a long-established law firm.

For example, Seyfarth Shaw, with more than 800 lawyers, began developing in 2008 what became its SeyfarthLean program, after clients started asking for alternative fee arrangements. For what is called continuous improvement, the firm’s SeyfarthLean team regularly cycles through each department looking for ways to improve work processes: better, faster, cheaper.

The 65-lawyer, full-service Barley Snyder firm with offices in central Pennsylvania also began targeting efficiency in the mid-2000s, eventually embracing Lean Six Sigma. But LSS still is one of those business management programs whose mention (except to the cognoscenti) tends to elicit a kind of skeptical laughter reserved for catchphrase gimmicks.

“I’d have the same knee-jerk reaction that this is hocus-pocus BS,” says Hunoval. “But the results just blew me away. There is a little hokiness to it, but the damn thing works. So I like the skepticism. Strategically it means we can be out in front for a bit before it catches on among law firms.”

Christi Hunoval: “We’re working to overcome the mindset that a foreclosure firm can’t also handle litigation, that they need to kick the cases over to a litigation firm.” Photo by Randy Piland.

MARRIED TO THE FIRM

While Hunoval’s own office is devoid of any sense of a woman’s touch, there is one in the firm’s leadership. His wife, Christi, left her litigation practice in the Charlotte office of South Carolina’s biggest firm, Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough, in the summer of 2012 to join her husband’s venture. The two met when they were associates in Nelson Mullins’ Columbia, S.C., office, before he moved on to other firms in Charlotte.

Christi Hunoval, a South Carolina native, is a steel magnolia “with major litigation chops,” as her husband puts it. She runs the litigation department with two other lawyers and some paralegals, accounting for 7 percent of revenues last year, which Matt expects to increase by half next year. Last May, former Nelson Mullins colleague Brian Calub, who clerked for a U.S. bankruptcy court judge, came to the firm as its managing litigation attorney.

“We’re working to overcome the mindset that a foreclosure firm can’t also handle litigation, that they need to kick the cases over to a litigation firm,” Christi says. “It’s frustrating to see cases yanked when we already had the institutional knowledge working the default and thought we could have done them better.”

A lot of the litigation is started by debtors representing themselves, often using templates found online or obtained from lawyers for complaints and other filings, though bankruptcy and other consumer-oriented lawyers bring cases, too.

Christi Hunoval is now the firm’s managing member, with Matt designated as founder. That arrangement led to theirs being certified last April as a woman-owned business enterprise by the National Women Business Owners Corp.

Matt Hunoval, though always in a hurry while also trying to heed advice from the firm’s finance director, has carefully been putting together a team of lawyers with what he sees as added value for the firm itself, more than just lawyering. (He hasn’t overspent on growth. His only debt is the mortgage on the firm’s building, and he carries a $300,000 line of credit.)

For example, in March last year Hunoval hired Les Blankenship to run the South Carolina default practice. Blankenship had litigated matters for mortgage servicers in the Charleston, S.C., office of the Finkel Law Firm, which has a broad practice but does the lion’s share of the state’s default work.

One year earlier, Hunoval hired Cameron Scott, who spent 4 years as an assistant clerk in the Superior Court of Mecklenburg County presiding over tens of thousands of foreclosure cases, a largely administrative role but a good one for developing networks and a big-picture view of the practice statewide. It helps, Hunoval adds, that Scott knows the clerks in all 100 North Carolina counties and taught some of their continuing education courses.

What the staff has achieved has already drawn high praise.

“What Matt Hunoval has accomplished is pretty staggering,” says LSS consultant David Skinner, a principal of Gimbal Law Practice Management Advisors, based in Montreal. Though he hasn’t worked with the firm, Skinner reads reports of its LSS progress, corresponds with Hunoval and believes others in the practice area will be forced to take notice.

Most importantly, Hunoval wants his staff “to buy into it. I want it in the DNA of this firm.” That way they can have pride of ownership in their own jobs by getting clear knowledge of how their work and that of the others fits together. They don’t just fasten widgets on products they don’t understand.

“We have regular meetings to discuss what everyone is doing in the process,” says Kim Langdon, a paralegal with the firm who specializes in South Carolina defaults. “It makes us aware of what everybody does, why people do certain things, and why you need to do it in the time frame. And there is some cross-training for scalability. If things get backed up in one area, someone can come over and help out.”

Blankenship soon noticed that too many South Carolina draft complaints contained errors or lacked documents. And that’s how Langdon’s job came to be changed. She used to do the document prep for drafting complaints. Now someone below the level of a paralegal handles the time-consuming gathering of documents, freeing up Langdon to concentrate on the complaints, and also to follow up on process servers later, which had been someone else’s task.

In January, the firm was one of five finalists for the Best Process Improvement Project at the 15th annual PEX awards, along with Capital One and Pitney Bowes—the winner. Hunoval’s entry was about changing how work is done.

“We keep working the bubbles out,” says Hunoval, describing the LSS process of continuous improvement. When you create a process map and find several problems, first attack the one that might account for 80 percent of the trouble; then start over and deal with the next one that rises to that level.

One of the most noticeable things for a visitor touring the building from department to department is the quiet, unhurried atmosphere. It is not a sweatshop. But everyone is always aware of targets, goals and needs. It becomes, Langdon says, “like a game in which you try to beat your own best time.”

Large flat-screen monitors mounted on walls in common areas, such as above photocopy machines, display color-coded spreadsheets detailing the past month’s workflow and totals in various tasks. At the bottom of the screens, graphics that look like streaming stock quotes carry status updates on case files, from intake to courthouse, showing where they are in each stage of the process and making it easy to spot problems that could slow or even halt their work.

“You can keep a constant check on your progress, and I can maybe adjust what I’m doing that day to work on complaints more rather than on amendments to those already filed, because it’s crucial to get that first complaint out,” Langdon says. She started at the firm in August 2012, before LSS came into play. “The difference has been like night and day.”

Photo of Matt Hunoval by Randy Piland.

LIMITED ENTRY

There are six entrances to the Hunoval firm but no lobby and no receptionist. All doors are locked. You don’t come to the offices unless you’re expected.

The nondescript, 22,000-square-foot office building is tucked into an industrial corridor along I-77 in the southern area of Charlotte, 5 miles from the South Carolina border. (Hunoval’s business gauge: 70 percent of the key population of the Carolinas is within a 1-hour and 45-minute drive.)

Hunoval moved there a little more than a year after launching his business in a 300-square-foot, open-cube space. That first office shared amenities and a frat-house atmosphere with six or seven other 20- and 30-something tenants—young entrepreneurs, including a Web developer and a purveyor of splash-screen ads for urinals—along with a refrigerator typically stocked with beer, Mountain Dew and mustard.

Hunoval leased 1,600 square feet in the current location in September 2010. He had started out handling 10 to 15 foreclosure files monthly, and in less than six months it grew to about 100. When he was offered an opportunity to expand into South Carolina, it was time to get bigger space. Now the count is about 500 monthly, with significant growth expected from the two new “whales,” if Hunoval’s LSS approach suits them.

Hunoval bought the building outright in October 2012. All entrances to his offices have video-recording security cameras, with keycard access only, part of an extensive and expensive array—he estimates $400,000—of security measures and documentation to ensure compliance with rules and regulations concerning private information in foreclosure files.

Hunoval now uses 75 percent of the building, with only an airline flight-attendants union and a cleaning service as his remaining tenants.

That security infrastructure might soon give Hunoval some advantage in a fast-growing sideline to his foreclosure business—real estate closings. It’s more work on the same dirt if he can do the foreclosure and then handle the sale. And he has a unique approach that appeals to real estate agents and lenders looking for convenience: virtual closings.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued new regulations in January requiring certain building and data security measures for financial institutions and, in turn, those institutions will develop approved lists of law firms that can provide such security for records involved in closings.

“I think it’s going to force onesy and twosy guys who do occasional closings to take early retirement or go do something else,” Hunoval says. “And of those left standing, we’ll see who is willing or able to make the new, required investment in infrastructure. Some of our competitors are run by longtime patriarchs with the force of personality and maybe little incentive to make the investments or change their cultures. Five years from now, we could be in a very good position.”

The closing business began as a hedge. Foreclosures have declined in the past year to pre-economic collapse levels, and closings are in some ways the other face of that coin: When one side is up, the other likely is down. Hunoval’s John Langston is pioneering the virtual closings, in which he and another lawyer can attend via television screen through an Internet connection, typically in the offices of real estate agents. They do about 150 closings monthly, 30 or so virtual. Until last summer, roughly 90 percent of them were lender-owned properties. Now, two-thirds of the business is ordinary closings.

“I see this as our real future, frankly,” says Hunoval. North Carolina and South Carolina are among a number of states that require lawyer involvement in closings. But the practice is balkanized, with one firm typically dominating a particular area of a city or county. “I want us to be the first firm with a truly statewide reach. I’m betting the farm this will literally transform how closing practice is done in the Carolinas.” He has been in talks recently with a large realty company that does more than 2,300 closings a year and might want to embed the firm’s virtual capabilities in its own office.

Hunoval has expanded with a toehold office in Virginia and is looking to Maryland next. Thus far he has grown by “green fielding,” or building his own, but Maryland might mean acquiring another firm.

And, of course, introducing it to LSS.

“It’s a question of how you inspire your people, how you get more out of them than they think they have,” Hunoval says. “I’ve got to communicate a vision and I’ve got to get everyone to buy into it.

“I’ve drunk the Kool-Aid.”

Sidebar

Mapping the Process

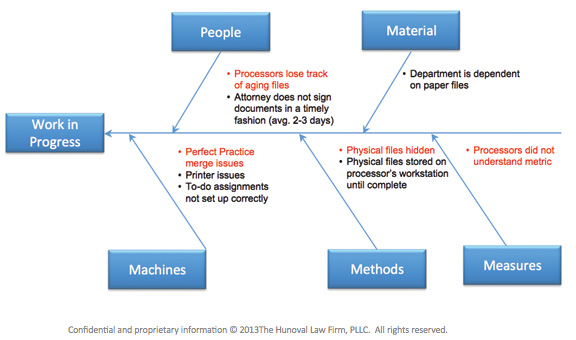

Often the biggest early gain to be made with Lean Six Sigma is also the simplest: a recognition that out of sight means out of mind. And it is common for the biggest and ripest of low-hanging fruit to be hidden from sight until each step in completing a task is dissected in what is called “process mapping.”

Outlining the problem of long delays, CIO Kevin Divine of the Hunoval Law Firm asked supervisors and staff in the firm’s North Carolina default department how long they thought it took from file intake to sending out a notice of hearing to launch the foreclosure process. Anecdotally, they saw it as 14 to 20 days. But the crunched numbers tallied 69.

“They were dumbfounded and somewhat defensive,” Divine says.

He met with the department manager and the two staffers: one who handles the substitute trustee aspect and the other who puts together the completed notice-of-hearing package.

They brainstormed in front of a flat screen displaying a dashboard, much like one on a car, except the gauges and measures concern target numbers and actual numbers for various stages in the process, with readouts color-coded green for good, red for bad and white for OK.

Ultimately, a big part of the cure would be to take files out of drawers and put them in plain sight on desks, and eventually to have cleared desks at the end of each day. But that answer came only after the team went through a procedure beginning with an LSS fishbone diagram (above). It details causes and effects throughout the various steps of a work in progress.

The Hunoval team mapped out the involvement of various people, machines, methods and measures. They analyzed each person’s actions in the process; specific involvement of computers (the “machines” in this case); every method, such as filing; and how progress is measured in the process from beginning to end.

The team reviews the dashboard monthly to see whether they are getting closer to target dates in various areas and to address problems.

Sometimes these areas, such as people and methods, can overlap; thus the realization that putting necessary files back in file cabinets at the end of the day and mixing them in with files that were not needed at the time was a problem.

“They were putting the needle back in the haystack every day,” Divine says.

Besides the forehead-slapping realization of forgotten files, the team found documents weren’t signed by attorneys in timely fashion; there was a reliance on paper files rather than scanning them into a database; to-do lists were set up improperly; and title searches remained incomplete.

This article originally appeared in the March 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Lean & Clean: Foreclosure firm goes statistical to improve speed and quality.”