Who's to blame for poisoning of Flint's water?

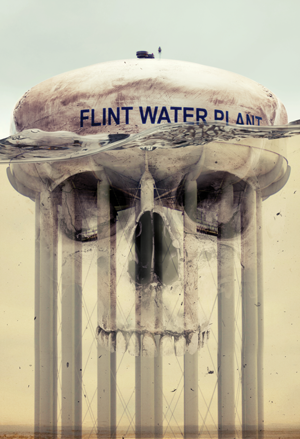

Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster

For LeeAnne Walters, the first sign of trouble came in the summer of 2014, when her 4-year-old son Gavin developed rashes after coming into contact with the water.

In July, Gavin and his twin, Garrett, both suffered scaly patches of skin that peeled after bathing. Several months later, Walters noticed her hair was falling out in large clumps that collected on her pillow and in the shower. Even her eyelashes were falling out.

By that time, the water coming out of her faucet was a dark rust color.

That November, tests of the water in her Flint, Michigan, home revealed that the concentration of lead was 104 parts per billion. The level at which the Environmental Protection Agency recommends updating pipes or adding anti-corrosives is 15 ppb, but some experts say that no level of lead is safe to ingest.

Her family immediately stopped drinking the water. Nonetheless, tests conducted on Gavin four months later revealed a blood-lead level of 6.5 micrograms per deciliter. Anything above 5 micrograms indicates lead poisoning.

“Anger doesn’t begin to cover it,” the mother of four says of her feelings about the situation. “I want the people who allowed this to happen to be held accountable.”

Walters, like numerous other Flint residents, is suing as a result of the disaster. But whether and when anyone will be held accountable is a lingering question for her and thousands of others affected. With lawsuits and criminal prosecutions being added to court dockets, there’s plenty of finger-pointing.

THE COST OF SAVING MONEY

Flint’s now infamous water problems stem from an ill-fated attempt to save money by disconnecting from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, which had provided the city with water from Lake Huron for decades.

Faced with budget deficits, Flint was ordered into receivership in 2011 by Gov. Rick Snyder. The move enabled him to appoint a series of emergency managers to run the troubled city, which had seen its population shrink to 100,000, from double that figure in the 1960s. Today, 41 percent of the city’s residents live below the poverty line in the struggling city, which is 57 percent black, 36 percent white and 4 percent Latino, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

One of those emergency managers, Darnell Earley, was in charge of the city in April 2014, when officials made the disastrous decision to switch water sources from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The move was supposed to be an interim measure through 2016, when a new pipeline would let the city connect with the Karegnondi Water Authority, which drew its water from Lake Huron.

Government officials repeatedly assured Flint residents that the water was safe. In fact, however, the Flint River was so corrosive it ate away at the pipes in the city, causing lead to leach into the water supply, poisoning the city’s residents—including 9,000 children younger than 6. While lead can be toxic to anyone, its effects on young children are particularly devastating. The well-documented array of symptoms caused by lead poisoning in children includes damage to the nervous system, bones, kidneys and hearing, as well as speech and language impairments.

Later, during state legislative hearings on the crisis, it emerged that Flint’s water hadn’t been treated with chemicals that would have made it less corrosive to pipes, a fix that would have cost only $150 a day. But before anti-corrosion chemicals could be added, the city needed to upgrade its equipment, which would have cost an estimated $8 million.

Read more: Lead Litigation Beyond Flint

The Flint Water Crisis: A Timeline

Beyond Lead

In addition to dangerous lead levels, the Flint River also may have had more pollution than Lake Huron: Soon after the switch, E. coli bacteria were found, prompting advisories to boil the water. Officials boosted the chlorine levels to control the bacteria, but a byproduct of chlorine is trihalomethanes—which can pose independent health risks, especially in people with compromised immune systems.

Melissa Mays. Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

On top of those problems, Flint also saw an increase in Legionnaires’ disease, which sickened 91 people and claimed 12 lives after the city switched water supplies. This was an extraordinary number: Typically, between six and 13 cases per year are confirmed in Genesee County.

At General Motors’ Flint plant, the water was so corrosive it rusted engine parts. The car company was able to disconnect from the Flint River in December 2014 and hook up to the water used by nearby Flint Township.

Flint residents didn’t have this option. Families had no choice but to accept water from the Flint River until October 2015, when the city reconnected to Detroit Water and Sewerage. That move came several weeks after Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, director of the Michigan State University and Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative, reported that the percentage of children in Flint with above-average levels of lead in their blood had almost doubled since the city stopped using water from Lake Huron. In one Flint neighborhood with especially high amounts of lead in the water, the proportion of kids with lead poisoning had tripled from 5 percent to almost 16 percent.

Even after the city reconnected to Detroit Water and Sewerage, the crisis continued. In January 2015, the federal government declared a state of emergency, which remained in effect until this August. By then, lead levels in Flint’s water had fallen between 50 and 80 percent.

As of mid-2016, numerous lawsuits had been filed in federal and state courts against Michigan and Flint officials, including Gov. Snyder. Some have been brought as class actions, while others were brought on behalf of individual parents, such as Walters. Nonprofits, including the NAACP and the Natural Resources Defense Council, have also sued.

“It’s incredibly troubling to see how long the situation persisted, and to see how long government officials at every level were aware of the problem before any meaningful action was taken,” says Dimple Chaudhary, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council. The NRDC is asking for an injunction that could require the government to replace all the lead service lines in the city at no cost to Flint residents.

“There are still open questions about how damaged the pipes are and how the system will be able to implement corrosion control,” Chaudhary says.

SICKNESS AND IMMUNITY

Melissa Mays, lead plaintiff in several of the class actions, says many Flint residents have suffered the kinds of physical ailments that warrant compensation.

“Everybody I talk to is sick,” says Mays, who helped launch the activist group Coalition for Clean Water.

Trachelle Young. Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

Two years ago, Mays worked for five different radio stations as a music promoter and went to the gym at least four days a week. Now she suffers from debilitating arthritis, bone spurs and seizures, and she recently had polyps removed from her stomach.

Her three sons, ages 11, 12 and 17, have brittle bones; her middle child recently broke two bones in his wrist. Her husband now has dizzy spells so severe he’s missed work.

While there’s no real question that the water was contaminated, it’s not yet clear whether Flint residents will be able to prove their illnesses were caused by the water, as opposed to other factors. And even if they can, obtaining civil judgments against a state governor and other heads of agencies won’t be easy, given that Michigan confers immunity on its high-ranking officials for decisions made while carrying out their responsibilities.

Sovereign immunity, an established common law concept, protects government entities and their employees from civil lawsuits. Michigan codified that principle in its Governmental Tort Liability Act, which provides that the governor and heads of agencies are immune from liability for torts committed in the course of their duties.

By contrast, the statute allows for suits against lower-level officials who have acted with “gross negligence”—defined by Michigan’s immunity law as “conduct so reckless as to demonstrate a substantial lack of concern for whether an injury results.”

Some plaintiffs are attempting to defeat an immunity defense by contending that government officials violated the constitutional rights of Flint citizens. A federal civil rights law, 42 USC S 1983, provides for civil rights lawsuits against state actors regardless of immunity laws.

But the plaintiffs in Flint may face an uphill battle in a civil rights case, according to Peter Hsiao, an environmental lawyer with Morrison & Foerster in Los Angeles. “I think a court is going to look very critically at a claim that these actions amounted to a violation of civil rights,” he says.

The plaintiffs in Flint raise several different constitutional claims, including allegations that officials violated residents’ rights to due process of law by endangering their “fundamental liberty interest to bodily integrity,” as well as claims that officials engaged in racial discrimination.

One of the civil rights claims that’s drawing attention centers on allegations that officials affirmatively created a situation that endangered residents of the city. That theory, known as “state-created danger,” dates to the 1989 Supreme Court case DeShaney v. Winnebago County, brought on behalf of a 4-year-old boy who suffered brain damage after being beaten by his father. The boy’s lawyers argued that child welfare authorities who were monitoring the home violated his civil rights by failing to protect him from his father.

The Supreme Court rejected that position but wrote in the opinion that government employees could violate people’s civil rights by affirmatively endangering them.

Subsequent decisions elaborated that government employees must act in a way that “shocks the conscience” before they’re liable for violating people’s rights by creating a danger.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs in Flint believe they can meet those standards. Michigan officials “made a deliberate decision not to use standard processing of the water to make it safe,” says Michael Pitt of Royal Oak, who represents plaintiffs in several of the lawsuits.

“Not only did they create the danger; they prolonged it,” he says. “Unfortunately, people died because they lied,” he adds, referring to residents struck by Legionnaires’ disease. “And maybe some people are going to die from the lead poisoning.”

Pitt notes that a federal judge refused to dismiss a recent lawsuit alleging that officials with the Philadelphia Housing Authority created an environmental hazard that endangered residents in that city.

In that matter, three families who resided in the Hill Creek Apartments say employees of the Philadelphia Housing Authority exposed tenants to asbestos. The employees allegedly discovered asbestos while fixing leaky pipes and crammed the substance into a wall instead of disposing of it.

Michael Pitt. Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

Lawyers for Michigan’s governor argue that the cases against him should be dismissed. Among other arguments, they say the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Cincinnati only recognizes the state-created danger concept when the state causes a risk of individuals being harmed by “third parties.”

Contaminated water, Snyder’s lawyers argue, is not a third party. However, plaintiffs countered in a brief filed in September that “It is illogical to claim that public officials cannot be held liable for creating a danger and injuring a plaintiff, whereas they may be held liable if they created or increased a risk of harm that was carried out by a private third party.”

OFFICIAL DIFFICULTIES

Proving that Michigan officials’ decisions amounted to a civil rights violation also could be difficult because doing so will require proof that the problems with Flint’s water were the result of misconduct that surpasses simple negligence.

“One of the problems with establishing a substantive constitutional violation is that you have to make the case that the conduct goes beyond a simple tort,” says Robert Allen Sedler, a law professor at Wayne State University. “That may be a heavy burden.”

Sheldon Nahmod, a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law, says the litigants likely will have to show that the government officials followed at least a “de facto” policy—meaning that they “were aware of the risk and continued in their course of conduct.”

Nahmod, author of the treatise Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Litigation: The Law of Section 1983, adds that there isn’t a great deal of precedent on the subject because environmental matters typically are dealt with in court through enforcement of environmental laws.

Proving a civil rights violation isn’t the only hurdle for the plaintiffs. Government officials also argue that a separate federal statute, the Safe Drinking Water Act, precludes all other causes of action. That law, originally passed in 1974, aims to comprehensively protect the country’s drinking water.

In April, U.S. District Judge John Corbett O’Meara agreed with that argument and dismissed a civil rights lawsuit brought on behalf of several Flint residents and a local business. That case, Boler v. Earley, was filed in January by prominent Baltimore attorney William H. Murphy, who recently struck a $6.4 million settlement for the family of Freddie Gray—a 25-year-old who died after suffering a spinal injury in police custody.

The suit, which names a host of official defendants including Darnell Earley (one of the former emergency managers of Flint), Gerald Ambrose (another former emergency manager of Flint), Dayne Walling (former mayor of Flint), the city of Flint, Gov. Snyder, the state of Michigan, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, contained allegations that Flint residents’ constitutional rights were violated.

O’Meara ruled that the Safe Drinking Water Act precluded the plaintiffs from pursuing civil rights claims. “The crux of each of plaintiffs’ constitutional claims is that they have been deprived of ‘safe and potable water,’ ” O’Meara wrote. “Plaintiffs’ allegations are addressed by regulations that have been promulgated by the EPA under the SDWA.”

Dimple Chaudhary. Photograph by David Hills.

He relied on a 1992 decision, Mattoon v. City of Pittsfield, by the 1st Circuit at Boston, which also found that the Safe Drinking Water Act precludes civil rights lawsuits resulting from water contaminations.

“Comprehensive federal statutory schemes, such as the SDWA, preclude rights of action under Section 1983 for alleged deprivations of constitutional rights in the field occupied by the federal statutory scheme,” the appeals court wrote in Mattoon, which stemmed from a lawsuit on behalf of 68 Berkshire County, Massachusetts, residents who alleged they came down with giardiasis, commonly known as “beaver fever,” after drinking contaminated water.

The Michigan plaintiffs are appealing O’Meara’s decision.

Other Remedies

Even if officials like Snyder are immune from damages lawsuits, the plaintiffs have other possible avenues of recourse. Some, such as Walters, are pursuing lawsuits against outside firms, including the Houston-based engineering firm Lockwood, Andrews & Newnam Inc. and Chicago-based Veolia North America, which reviewed the water distribution system. Both of those companies are also facing civil lawsuits by state Attorney General Bill Schuette.

Melville, New York, attorney Hunter Shkolnik, who is representing plaintiffs in one of the class actions, says he hopes Congress will create a fund to compensate Flint residents. He says his firm has hired lobbyists on Capitol Hill.

“We’re working the halls,” he says. “We’re getting very good traction there.”

Even if high-ranking officials are never held liable in civil court, criminal charges are possible. The attorney general recently indicted three low-level officials—Mike Glasgow, Stephen Busch and Mike Prysby—on charges including conspiracy to tamper with evidence. The complaint contains allegations that officials manipulated test results by telling residents to “pre-flush” the taps before gathering water samples that were tested for lead.

Glasgow, the laboratory and water quality supervisor, pleaded no contest to willful neglect of duty, a misdemeanor, in early May. He said he will cooperate with an ongoing investigation that could result in charges against other officials.

In July, Schuette charged six additional state employees with misconduct and willful neglect in office. Schuette hasn’t yet said who else he is investigating. But some residents hope the probe reaches the very highest levels of government.

“The emergency manager, to me, was simply the method of the madness. The madness was the governor,” says Trachelle Young, a former chief legal officer for Flint who now represents some of the plaintiffs suing over the water contaminations.

Young was one of the first lawyers to sue over the switch to the Flint River, in April 2015. She represented a coalition of community members who sought an emergency injunction that would have required the city to switch back to the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. In June 2015, U.S. District Judge Stephen J. Murphy III in Michigan denied the request, writing that the plaintiffs’ legal theories weren’t yet developed.

Like others in Flint, Young is hoping to see more government officials involved in the water contaminations charged with crimes. As for the civil suits, Young says damages could be broad-ranging—from paying to replace pipes to medical monitoring to compensation for decreased property values.

Even though the lead levels in water overall had decreased by late summer, some say plenty of work still needs to be done.

“People still can’t drink their unfiltered tap water,” says the NRDC’s Chaudhary. “That’s really serious.”

And pockets of Flint still show unacceptably high levels of lead. “There are still hot spots,” Walters says. “There are a lot of things that need to be done. The longer it goes on, the worse the damage is.”

“The remedy’s going to be difficult,” Young says. “We’ve got people who will never trust water again.”

Read more: Lead Litigation Beyond Flint

Sidebar

The Flint Water Crisis: A Timeline

Lawyer and journalist Wendy N. Davis lives in New York City.

This article originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Who’s to Blame? Residents of Flint, Michigan, hope lawsuits and criminal prosecutions will hold decision-makers accountable for the poisoning of their water supply.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.