First Black federal judges carved a civil rights path

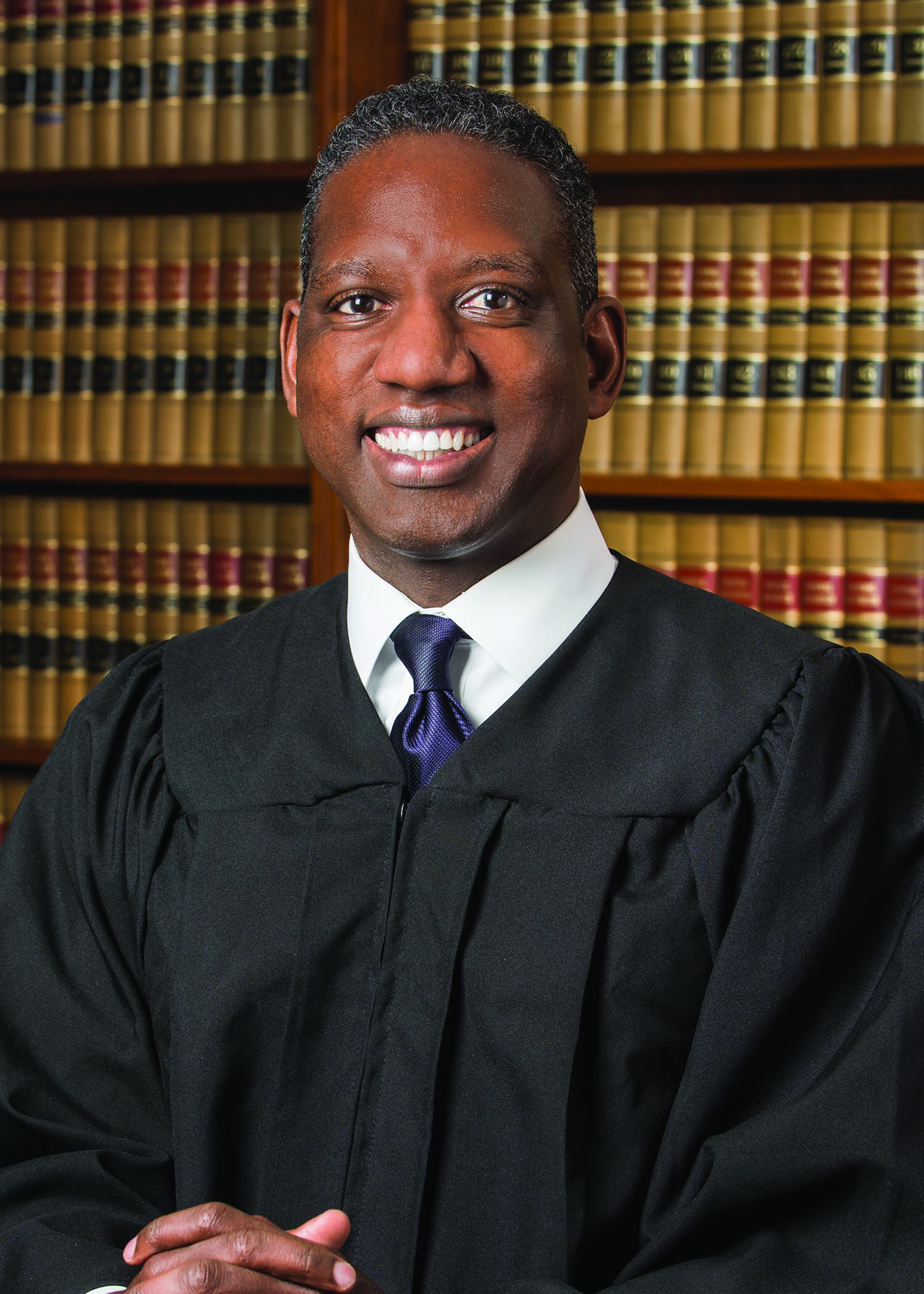

Judge Willie J. Epps Jr.

In 1950—just three years after Jackie Robinson smashed baseball’s color barrier—William Henry Hastie shattered the judicial glass ceiling, becoming the first Black judge appointed for life to a federal court of general jurisdiction.

Despite the wide-ranging celebration of Robinson integrating Major League Baseball, the mainstream press gave little notice of the ascent of Hastie and the next eight Black judges who followed him, all of whom endured a host of obstacles at the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement.

“They did not let barriers stop them from becoming federal judges when segregated schools, employers, restaurants, hotels, public bathrooms, water fountains and swimming pools prevailed,” says Willie J. Epps Jr., a magistrate judge in the Western District of Missouri.

In “The Jackie Robinsons of the Federal Judiciary,” published in the University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class, Epps recounts the strengths, struggles and legacies of these nine historic trailblazers.

What do these judicial pioneers have in common?

They were fortunate to be on the presidential radar screen—or at least on the radar screen of an influential U.S. senator. And quite simply, these firsts were giants in terms of their educational backgrounds, work experiences and political activity. They stand among the most accomplished and consequential legal figures of the 20th century—some litigating and winning the most important civil rights cases in our nation’s history.

Did they know each other?

Five pursued civil rights litigation prior to judicial appointments, with many influenced by Charles Hamilton Houston, the legendary Howard Law dean and trial lawyer. Hastie was Houston’s law partner, helping create the groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education. The pair worked closely with Thurgood Marshall, Spottswood Robinson and Constance Baker Motley at the [NAACP] Legal Defense Fund on landmark civil rights cases. Later, Robinson served on the federal trial and appellate courts in Washington, D.C.; Motley became the first Black woman on the federal bench; and Marshall the first Black Supreme Court justice.

Each faced adversity. How did that impact their careers?

Leon Higginbotham Jr., for instance, attended segregated public schools in New Jersey, but his mother fought for him to integrate Ewing Park High School in Trenton. He graduated at 16. Then he enrolled at Purdue University, where Black students were forced to live in an unheated barracks-style attic. One morning, he went to the university president’s office, requesting that the Black students live in dormitories. The president said the law did not require Purdue to let Black students sleep in dorms, and if Higginbotham didn’t like it, he could leave. Higginbotham transferred to Antioch College. The Purdue interaction inspired him to become a lawyer.

World War II ended just years before Hastie’s appointment to the 3rd Circuit. Did service impact the confirmations?

Several of the first Black federal judges served. I get the sense that patriotic military service helped veteran judges get confirmed. However, there were notable exceptions. Hastie never served in uniform but as a civilian aide to the secretary of war. In that top-level post, he helped chisel away at a segregationist system that would crumble within years after Hastie famously resigned the job in protest over the military’s continued segregation. Civil rights leaders thought Marshall, in his 30s, might be drafted. Hastie wrote a letter to the draft board on Marshall’s behalf asking them to consider the potential damage to the NAACP and race relations if Marshall were drafted. The appeal worked.

How did having a political background come into play?

Seven of the first nine had been involved in politics. For instance, Hastie served in President [Franklin Delano] Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet” and campaigned extensively for Harry Truman. James Parsons campaigned for a state trial judgeship and other Democratic candidates in Illinois the year before becoming a federal trial judge. And when President [John F.] Kennedy appointed Higginbotham to the Federal Trade Commission, he was the first Black appointed to any federal agency.

Did working on civil rights litigation help or hurt their appointments?

Hastie’s association with the NAACP LDF and National Lawyers Guild allowed some senators to falsely accuse him of being an enemy of democracy. His nomination was held up nine months and involved three separate Senate committee hearings. In contrast, Parsons, the second Black federal judge, had an easy two-week confirmation without a dissenting vote in the Senate. He had not litigated civil rights cases.

Talk about Marshall’s confirmation—one of the most contentious in Supreme Court history.

In June 1967, President [Lyndon B.] Johnson nominated Marshall to the Supreme Court, stating it was “the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place.” Still, Marshall’s hearing was delayed over a month. Then Sen. James Eastland (D-Miss.) reignited his claims that Marshall was a communist prejudiced against white Southerners. The opposition claimed Marshall would be too sympathetic to criminal defendants, unlikely to exercise judicial restraint and lacking in basic constitutional knowledge. Despite a six-hour minifilibuster, Marshall was confirmed by the Senate in August 1967, 69-11.

Motley faced additional barriers being a woman. What made her rise above?

Intellect, drive and determination. Motley was the first Black woman admitted to Columbia Law School, then practiced at LDF as a talented staff attorney on important civil rights cases. She worked to integrate countless Southern universities in the aftermath of Brown. She was the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court, winning nine of 10 cases. I only met Judge Motley once, so it is hard to compare her to my law school classmate Ketanji Brown Jackson. I do know they share a birthday and will always be known as brilliant and trailblazers.

Has there been progress?

Even in 1967, the number of Black federal judges could almost be counted on two hands. Today, Blacks occupy judgeships at every federal level, and a Black man and a Black woman serve on the Supreme Court. Our pioneers need to be celebrated and recognized, not just in sports, but in law and politics.

This story was originally published in the August-September 2023 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Called Up to the Major League: First Black federal judges carved a civil rights path.”

Character Witness explores legal and societal issues through the lens of attorneys in the trenches who are, inter alia, on a mission to defend liberty and pursue justice.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.