Genealogy sites give law enforcement a new DNA sleuthing tool, but the battle over privacy looms

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/Shutterstock

In 1996, Christopher Tapp confessed to the rape and murder of 18-year-old Angie Dodge in Idaho Falls, Idaho. He was convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison, but there was one problem: Tapp was innocent.

After he had already served a decade in jail, the Idaho Innocence Project at Boise State University took up Tapp’s case at the behest of a local public defender.

Greg Hampikian, executive director of the organization, said that it was clear from the beginning that aggressive police interrogation led to the false confession, but that was insufficient to secure Tapp’s freedom.

Hampikian thought that if the innocence project could get enough pieces of redundant evidence that showed someone else had committed the crime, “then we might be able to convince a judge of his innocence,” he says.

Hampikian, a biologist, reexamined a semen sample and pubic hair from the crime scene. The samples matched, but they didn’t match Tapp, a fact known at trial. During his false confession at the age of 20, Tapp said he moved a teddy bear during the commission of the crime. The stuffed animal was swabbed and tested—his DNA was nowhere to be found.

While evidence throwing doubt on his conviction grew, years clipped away as he languished in prison.

After a change in state law in 2012 allowing for retesting of DNA evidence, Hampikian retested samples from the crime scene and with those results used DNA databases and an ancestry website to piece together a family tree. One potential suspect, a filmmaker living in New Orleans, had been to Idaho in the 1990s and could be the perpetrator—so investigators thought. After obtaining a warrant for the filmmaker’s DNA, the lead became a dead end.

Then in 2018, CeCe Moore, chief genetic genealogist at Parabon NanoLabs, used the original sample from law enforcement to reverse-engineer the suspect’s family tree through the DNA sample, public records and news clippings. Through a process called genetic genealogy, she was able to narrow likely matches to a genetic couple with six male descendants who could be potential suspects. But, again, those people did not fit the profile of the killer.

“When we had pretty much ruled out the other six, I went back to the paper trail,” Moore says. “Sometimes there are people obscured by the record.”

She was right. There was another son in the genetic family tree, Brian Leigh Dripps Sr., who was raised by his mother and had taken a different family name and grown up apart from his biological father’s genealogical line. In 1996, he lived across the street from Dodge, the victim Tapp was convicted of raping and murdering. After his arrest, Dripps admitted to the murder.

In July 2019, Tapp—after being incarcerated for over 20 years—likely became the first person in the U.S. exonerated on account of forensic genealogy.

Tapp tells the Journal that through DNA and investigative work, everyone now knows what he’s known for the last 22½ years: That he’s innocent. “It was a humongous weight lifted off my shoulder,” he says. “It’s an amazing second chance.”

Exploring one’s ancestry is an American pastime. However, the unprecedented DNA data pool created by private genealogy websites provides a new opportunity to crowdsource leads in criminal investigations. This data has led to both an exoneration and a conviction this past summer—among dozens of other ongoing investigations and trials—and it is a technology and approach now in prime time. While law enforcement and the public largely welcome the new wave of forensic genealogy, others worry that privacy rights are being eroded by an investigative approach with little regulatory oversight.

Old tricks and new clues

Even if the recent onslaught of news coverage may indicate otherwise, DNA databases are not new. Since the U.S. DNA Identification Act of 1994, law enforcement agencies around the country have been collecting and searching the DNA of missing people, convicted felons and from crime scene evidence.

Some states also collect DNA from those arrested on felony and misdemeanor charges. These datasets are stored in the FBI-operated Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS. California has its own similar statewide system, which as of 2009 includes the DNA of those arrested on any felony charge.

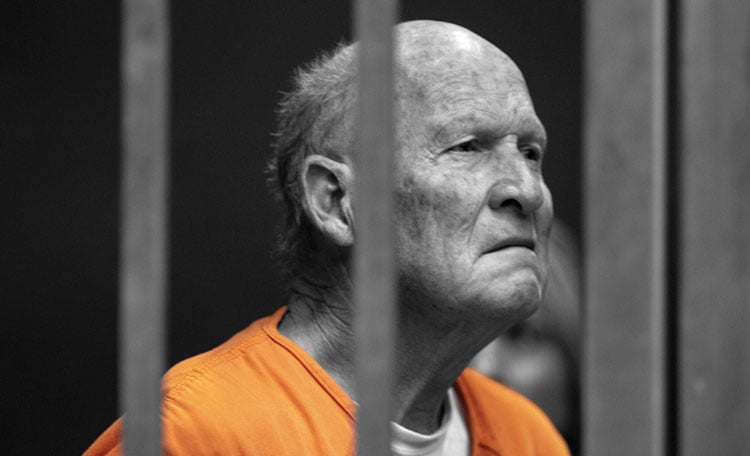

Joseph James DeAngelo appears in court in the “Golden State Killer” case. Photo by José Luis Villegas/The Sacramento Bee via AP, Pool

With these databases, law enforcement can run DNA against them to find matches or generate leads. With rare exceptions, CODIS was not developed to assist in the investigation of a family tree. Now, private companies have changed the game and expanded the data pool to include people with no criminal histories and looped in extended family members with no knowledge that they are in a perpetual genetic lineup.

These private databases have been around since at least 2000, which is when direct-to-consumer sales of the DNA tests began. Led by companies like 23andMe and Ancestry.com, the products let customers—through a mouth swab or spit—receive raw and analyzed data about their DNA. These companies collect more genetic markers than CODIS, including height, geographic ancestry or whether an individual carries a genetic disease or is a product of incest.

Once in possession of their DNA data, consumers can upload it to websites like GEDmatch and Family Tree DNA, which allow for people and law enforcement to search for missing relatives or suspects.

“You’re reverse-engineering a family tree,” says Leah Larkin, a genealogist and founder of The DNA Geek, which helps people find missing relatives. “It’s a lot like putting a puzzle together.”

Not just built on DNA, this technique includes public documents, news clippings, social media and other documents to re-create a family tree.

Through their growth in popularity over the last decade, DNA testing companies boasted 26 million users as of the end of 2018, according to the MIT Technology Review. Today, the databases are so robust that 60% of Americans with European ancestry are identifiable from DNA within these databases, according to research published in Science in 2018. That number is expected to jump to 90% in just a few years, researchers say.

This increased data pool has opened up a new avenue for law enforcement and genealogists to find fresh leads for investigations that long ago went cold, which also brought increased attention.

“Since the Golden State Killer case broke, it’s been an ongoing wildfire of media interest and public interest,” says Larkin, who does not take criminal genealogy cases for ethical reasons related to informed consent and government overreach. “Genetic genealogy was a sleepy little backwater hobby prior to that.”

Larkin is referencing the April 2018 arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo—the “Golden State Killer”—who was charged with eight counts of murder related to a prolific number of rapes, murders and burglaries committed in California between 1976 and 1986. With prosecutors seeking the death penalty, the trial is ongoing.

High-profile or not, forensic genealogy is used to develop leads to investigate a person and has so far not been used to generate probable cause warrants, which makes the technique hard to challenge in court.

A recent case

In a case from this past summer, Snohomish County prosecutors in Washington state brought charges against William Earl Talbott II for a cold-case double murder from 1987. Talbott was a suspect because of connections made from two relatives uploading their data to GEDmatch.

“There was a collection of potential hazards that came along with the evidence,” says Matt Baldock, a deputy prosecuting attorney and lead counsel on the Talbott case.

Having never prosecuted a case that started with a forensic genealogy lead, he was initially concerned that the approach could infringe on the public’s expectations around privacy and raise particular search-and-seizure and admissibility issues that could confound the case.

Talbott was added to the suspect list thanks to the work done by Moore at Parabon NanoLabs, which has been involved with over 50 similar investigations. Once she had reasonably narrowed down the possible suspects to Talbott, police followed him until he discarded a coffee cup from his truck. The cup was used to run a DNA test.

Public defender Rachel Forde (left) and William Earl Talbott II (center). Photo by Kevin Clark/The Herald via AP, Pool

Initially, the case was being heralded by an article in Wired as a novel legal fight that would “put genetic genealogy on trial.” Instead, the issue was resolved before the trial began, through a stipulation brought by the defense.

“Our position is that the genetic genealogy process and subsequent testing that they did was not relevant, because that was not used as evidence by law enforcement to arrest Mr. Talbott,” says Rachel Forde, one of two Snohomish County public defenders who worked Talbott’s case.

In Forde’s view, her client’s privacy and constitutional rights were not violated. Her team received the forensic genealogy reports from Parabon NanoLabs during discovery, the police did not break the terms of service of GEDmatch when pursuing the lead or use the genealogy report as probable cause for a warrant, and her client’s DNA was legally obtained.

One of the victims was believed to have been raped. What Forde took issue with was the conclusion that Talbott’s DNA found on the pants of the female victim connected him to a crime.

“We have to overcome a bias that juries already have: that DNA is meaningful in a criminal context, even if it’s divorced from the crime,” she says, meaning the existence of a person’s DNA at a crime scene does not logically conclude that person is the perpetrator of a crime. In her client’s case, she believes there are noncriminal reasons why his DNA was found on the female victim, like consensual sex.

However, she says, “It’s going to probably take some very tragic false convictions in order for people to understand that.”

In July, Talbott was convicted and sentenced to two life terms to be served consecutively. Believing he is innocent, Forde says her office plans to appeal. Meanwhile, her colleagues are already preparing for a new case that used forensic genealogy.

New terms of service

Working through the legal landscape of these tools is not just happening in court. GEDmatch and Family Tree DNA, the companies that allow for law enforcement searches, have been updating their terms of service in response to increased scrutiny.

GEDmatch, which was used in the Golden State Killer and Talbott cases, recently clarified under what circumstances it would permit law enforcement to search its database. According to an old version of its terms of service, law enforcement could use its database for investigating a violent crime. However, “violent crime” means different offenses in different states.

After receiving pushback for helping law enforcement in Utah investigate an assault, which some felt was not a “violent crime,” the company redefined its terms.

“There was a big backlash by a few people claiming that since the woman lived, this did not meet the existing [terms of service], and we were on a ‘slippery slope’ to letting [law enforcement] use GEDmatch for nonviolent crimes,” Curtis Rogers, a partner at GEDmatch, said in an email. “This case gave us the chance to both create the opt-in process and at the same time to revise our definition of ‘violent crimes’ to more accurately meet the FBI definition,” which includes murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery and aggravated assault.

The company also opted everyone who previously uploaded their data out of law enforcement matching with this update, requiring all new and old users to affirmatively opt-in to such searches.

Family Tree DNA, which got in trouble with its customers for secretly working with the FBI in early 2019, now only permits law enforcement to use the service for homicide, sexual assault or abduction cases, according to its law enforcement guide. Its privacy statement does not include abduction cases. The company did not respond to questions sent by the ABA Journal to clarify this and other issues.

By contrast, 23andMe and Ancestry.com have not opened their customers’ information to law enforcement without a warrant or subpoena. 23andMe’s Transparency Report shows it has received six government requests for data since 2015. Ancestry’s Transparency Report indicates it received 67 legal requests for user data over the same time, all related to credit card misuse or identity theft. The company reports that it did not receive any legal requests for health or genetic information.

These limitations may be moot, according to some, because law enforcement can create a typical user account and upload DNA from a crime scene, circumventing the terms of service.

More at stake

Regardless, most of the companies themselves maintain a unilateral power to change their contract language, which could affect the privacy of an individual’s genetic and health data, a worry of Jessica Roberts, professor at the University of Houston Law Center.

Adding to her concern, these companies that collect and analyze millions of Americans’ DNA are not health care providers, which means the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the leading federal law protecting health data, does not apply.

The fact that most consumers do not pore over the “clickwrap” terms of service for every app and website means that people might not know what their DNA is being used for. This, coupled with corporate America’s penchant for forced arbitration, leaves most consumers with limited legal recourse, she says.

Photo by SSPL/Getty Images

For the privacy-conscious, GEDmatch’s terms of service lays out a clear choice: “In the end, if you require absolute privacy and security, you agree that you will not provide your personal information, raw data or genealogy data to GEDmatch.”

As terms of service are updated and appellate courts await these cases, some advocates worry that this new approach infringes on not only the privacy of the user, but the user’s extended family.

“I think there’s certainly privacy interests and troubling privacy implications of this investigative technique,” says Vera Eidelman, a staff attorney at the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project. “And I think a lot of that stems from the fact that DNA is deeply personal, deeply sensitive. It is unique to each of us.”

Raising the idea of “networked privacy,” Eidelman explains that not only does someone give up their privacy by using a product like GEDmatch, they also give up the privacy of their genetic relatives.

While she isn’t sure there are clear constitutional claims raised by forensic genealogy, “the implications are quite concerning,” she says.

Even with these concerns, the general public and genealogists seem relatively comfortable with law enforcement’s use of this technique in some circumstances.

“We were tracking the news, and privacy was usually called out in the media reports that were coming out about [the Golden State Killer’s] arrest,” says Christi Guerrini, an assistant professor at Baylor College of Medicine and a lawyer, “but when I read reader comments, it seemed that a number of people were quite happy to trade their privacy interests in exchange for what they consider to be a safer community.”

In a survey conducted by Guerrini and her colleagues, published by scientific journal PLOS Biology, 91% of respondents supported law enforcement’s use of this data to investigate violent crimes. Seventy-five percent of those surveyed were even comfortable with police creating fake accounts to use genealogical websites to investigate violent crimes. However, support cut in half to 46% if the databases are used to chase nonviolent offenses. The survey polled 1,587 people on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing website, in May 2018.

In a separate 2018 survey of 640 members of the genealogy community, self-published by Maurice Gleeson, a genealogist in Ireland, 85% of respondents were “‘reasonably comfortable’ with the use of their DNA results by law enforcement agencies (for catching serial rapists and killers).” Similar to Guerrini’s survey, fewer respondents—47%—were supportive of law enforcement using these databases for investigations of nonviolent crimes.

Even with public support of this approach, GEDmatch is not seeing a flood of users opt-in to law enforcement searches after it changed its terms of service earlier this year.

“Initially when we implemented the opt-in system, the number of people on our site with whom [law enforcement] could compare dropped to zero,” Rogers says.

The website also opted everyone who uploaded their data before May 18, 2019, out of law enforcement matching, which left some feeling bereaved, at least temporarily.

“That data is lost; it’s like burning libraries,” says Moore at Parabon NanoLabs.

Since Oct. 1, about 170,000 users have opted-in to GEDmatch’s law enforcement matching.

Still, Moore and others are worried that actions from companies and government regulators could continue to limit the reach of forensic genealogy.

A legislative future

Maryland and Washington, D.C., have already reined in the practice of “genealogical searches” of law enforcement databases like CODIS. Maryland’s law, which was passed in 2008, did not foresee privately held DNA databases.

“The policy in the state of Maryland is pretty clear: We shouldn’t be doing this,” says Maryland House Delegate Charles Sydnor III.

To close the loophole, he proposed a bill during the last legislative session that would have effectively banned the practice of using private databases for forensic genealogy to connect someone with a crime. The bill did not make it out of committee.

While soliciting feedback from experts in biology, law and policing, he anticipates bringing a version of the bill back for the 2020 legislative session.

Without regulation in this space, like adding these companies to the list of covered entities under HIPAA, Moore, also active in a genealogy trade group, says she’s in favor of an industry certification for genealogists working on criminal investigations. But it has been a hard sell to her colleagues.

As forensic genealogy gains more attention and use, she says it’s important for people to have a sensitivity to the ethics and confidentiality required to dig into someone’s family tree for a criminal investigation.

A certification could include previous experience in unknown parentage, the act of finding family of an adopted child, which is good training for criminal investigation applications, she says.

Larkin, a genealogist focused on unknown parentage, also believes that training and certification are necessary to provide oversight of a technique that can lead to an individual’s loss of liberty and privacy. However, this lack of industry standards isn’t likely to hold back the growth of this burgeoning industry and its use by law enforcement.

“I don’t think this is going away,” Larkin says. “I think this is the new normal, and I don’t think that law enforcement is going to give up the power of this tool.”

This article ran in the Winter 2019-2020 issue of the ABA Journal with the headline “Blood Ties: Family-tree genealogy sites arm law enforcement with a new branch of DNA sleuthing, but the battle over privacy looms.”

Correction

Print and initial web versions of “Blood Ties,” Winter 2019-2020 issue, should have made clear that Parabon NanoLabs did not identify a filmmaker as a potential suspect in a rape and murder case. And a process Parabon Nanolabs used should have been referred to as genetic genealogy.The Journal regrets the errors.