'Queen of Pro Bono' Esther Lardent passes away after 40-year career

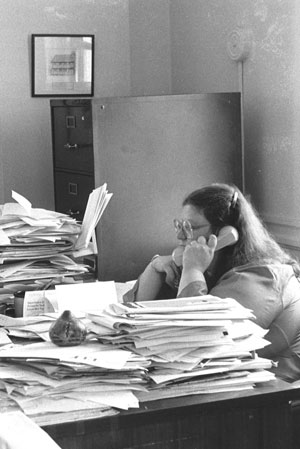

Esther Lardent at her desk. Photographs courtesy of Pro Bono Institute.

For more than four decades, Lardent wore so many hats in the ABA—often several at a time, from staff member to consultant to committee chair, even a stint on the Board of Governors—that it sometimes got confusing, even problematic. She was widely known simply by her first name.

A couple of inches taller than 5 feet, and for much of her life well over 300 pounds, Lardent was professionally and by personality larger than life. Praised by justices and judges who pushed pro bono efforts, called a genius by big-firm managing partners, she regularly danced with abandon at parties, often barefoot, always with a smile framed by an expression like that of a very happy child.

That was remarkable given Lardent’s background. She was born in a displaced-persons camp in Lienz, Austria, to parents who met there after being liberated from death and work camps at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, after losing their spouses and families in the Holocaust. Lardent believed that she was born on April 23, 1947, according to the transcript of her oral history taken by the Women Trailblazers in the Law Project of the ABA’s Senior Lawyers Division.

They lived in the camp and then traipsed through Europe and Israel during Lardent’s first four years, searching in vain for her half-sister, who had entered Auschwitz as an 8-year-old and probably died there, and for her father’s family. Then, with little money and speaking no English, the Fersters came to the United States through Ellis Island and settled in Springfield, Massachusetts.

A brilliant student, Lardent received a full scholarship to Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, under a program for the disadvantaged. She then went to the University of Chicago Law School, where she received her JD in 1971.

Lardent often said her work on legal services projects was “my way of paying back for all that this country has done for me and my parents.”

INSTIGATING A CULTURAL SHIFT

She gave back many times over. Through her efforts, according to statistics from the Pro Bono Institute, which Lardent founded, law firms have contributed 60 million pro bono hours over the past 20 years. She created the Pro Bono Challenge, signed by 137 firms that dedicate 3 to 5 percent of their total billable hours to pro bono work in a kind of tithing that now averages 4.2 million hours annually. A similar challenge to corporate law departments begun 10 years ago now has 145 signatories, for which about 7,000 in-house lawyers perform pro bono legal services each year.

“Pro bono is now an integral part of what lawyers in firms and corporate law departments do,” James Jones, the principal at Legal Management Resources in Reston, Virginia, and chair of the board of the Pro Bono Institute, told a gathering of about 150 people on a June workday in Washington, D.C., to celebrate Lardent’s life. “And that represents a very significant cultural shift.”

Until Lardent brought emphasis, organization and structure to pro bono legal services, few firms took more than an occasional, ad hoc approach to such work. She launched one of the first organized pro bono efforts in the late 1970s as executive director of the Boston Bar Association’s Volunteer Lawyer Project. She then became chief consultant to the ABA’s Post-Conviction Death Penalty Representation Project, getting mostly big-firm lawyers to take on death row inmates’ state and federal appeals.

Lardent decided to expand such efforts to encompass access to justice in general for those who can’t afford it. She developed the ABA’s Law Firm Pro Bono Project in the early 1990s, going to the big firms for help.

“Esther’s secret was to get people to do something they like, and they’d end up doing more and more of it,” says Robert C. Sheehan, who was executive partner of New York City’s Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom when he came into Lardent’s fold in the 1990s, co-chairing the Pro Bono Institute’s law firm advisory committee. He now is of counsel at Skadden Arps.

ACTS OF GENIUS

But there was more to Lardent’s recipe. She developed pledges, benchmarks and awards. Law firms would know details of each other’s pro bono work, as Lardent spread the gospel of doing well by doing good. Pro bono, she would explain, is an asset—not a drain. It is a draw for top talent, good for morale and provides training as well as a kind of public relations that couldn’t be bought.

“Esther recognized the importance of competition and recognition in motivating people,” says James Sandman, president of the Legal Services Corp., who first worked with her when he was managing partner of Arnold & Porter in Washington, D.C., a position also held by Jones. Sandman notes that Lardent drew up the connection that let pro bono performed by in-house lawyers be credited as part of overall corporate social responsibility efforts, then got the law firms and corporate law departments to motivate each other to do more.

“It was genius,” Sandman says. “It had never occurred to anybody to do those things.”

Lardent was known for her ability to see ahead when problems arose and to devise the right strategy for a fix, and a number of ABA presidents during the 1990s and 2000s wanted her in the room during such times.

When Lardent joined the Board of Governors in 1996 for a three-year term, there was some pushback concerning possible conflicts because of her grant-paid consulting role on pro bono matters. Her solution: She created the Pro Bono Institute as an independent nonprofit, taking the Law Firm Pro Bono Project and its Ford Foundation grant with her, though continuing to pursue new roles at the ABA, such as chair of the Commission on Immigration, which she helped create, and as a member of the House of Delegates.

“Esther was a doer, an accomplisher, and when she saw a need, she charged right into it,” says Robert E. Hirshon, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School in Ann Arbor who served as 2001-02 ABA president. “You might have disagreed with some of her approaches, but you could never disagree with her level of commitment.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Passing of Royalty: Esther Lardent, a key figure in the pro bono legal services movement, died April 4.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.