Drug crimes prosecutions could be taking a back seat as the DOJ focuses on unlawful entry

Photo by Jaime Rodriguez Sr./U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions positioned himself as a hardliner against crime during his 21 months in office. He called for more use of the death penalty, revoked a Department of Justice policy intended to avoid mandatory minimum sentences and revoked another against prosecuting marijuana businesses that are compliant with their states’ legal marijuana laws.

And perhaps most famously, in April 2018, Sessions instituted the “zero tolerance” policy for immigrants who cross the border without authorization, requiring federal prosecution for every offender caught. That policy got widespread attention last year after the Trump administration began citing it as a reason for separating immigrant children from their parents, a practice that was officially ended in June 2018 after widespread outrage.

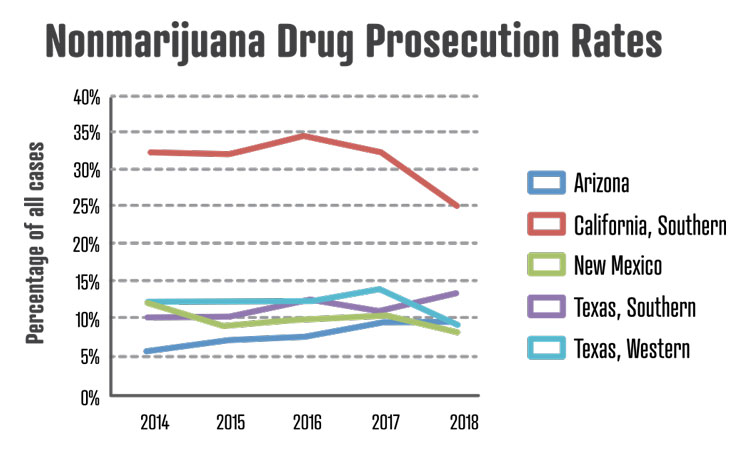

But less noticed was the effect zero tolerance may have had on other kinds of prosecutions. Statistics compiled by the ABA Journal suggest that as misdemeanor unlawful entry prosecutions rose between 2017 and 2018 in the five federal districts along the southwest border, federal prosecutions for nonmarijuana drug offenses dropped. That’s while apprehensions of people crossing between official ports of entry reached a 17-year low in fiscal 2017, and U.S. Customs and Border Protection drug seizure statistics were largely up, suggesting no lack of referrals.

resource issue

Thus, despite the Justice Department’s tough-on-crime stances, the increased demand on U.S. attorneys’ offices from zero tolerance may have hurt those offices’ ability to pursue other—likely more serious—prosecutions. That’s the core mission of federal prosecutors, and moving away from it could have a negative effect on public safety.

“It takes resources away from more serious crimes and spends a lot of resources in an area that there’s not going to be much deterrence on,” says Kara Hartzler, an appellate attorney for the Federal Defenders of San Diego.

The drop in federal prosecutions for nonmarijuana drug offenses may not necessarily be a result of DOJ policy. Former U.S. attorneys offered various nonpolicy explanations for the drug data. Because drug seizures are mostly up, however, the numbers can’t be explained by a lack of crimes or a lack of arrests.

But former U.S. attorneys also say a policy of prosecuting everyone caught crossing the border illegally would have strained the resources of their offices—and, by necessity, diverted attention from other kinds of cases.

ABA Journal Infographic

“Just to give you an idea of scale, I think my peak year, we prosecuted a total of about 3,000 [misdemeanor unlawful entry] cases,” says David Iglesias, who served as U.S. attorney for the District of New Mexico from 2001 to 2007. “So [if] you get 100,000 people coming over, you cannot possibly physically prosecute that many people.”

‘Zero Tolerance’ Prosecution rates

Zero tolerance calls on the U.S. attorneys’ offices along the southwest border—the Southern District of California, the Western District of Texas, the Southern District of Texas and the districts of Arizona and New Mexico—to prosecute all referrals for misdemeanor unlawful entry, according to Sessions, “to the extent practicable.”

The caveat from Sessions might have been necessary, because even though immigration cases are the bulk of most border districts’ work, the volume of border crossers has historically made it difficult to prosecute all or even most people caught. U.S. attorneys’ offices have historically declined the bulk of the misdemeanor cases, although the potential defendants were still put into deportation. Multiple former U.S. attorneys described deliberately deciding to focus their resources on more serious immigration crimes.

“Because of the resources, we focused primarily on those involving felony convictions, those that illegally re-entered upon deportation,” says Kenneth Magidson, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Texas from 2011 to 2017. “We had our plate full with just those cases.”

Indeed, a bipartisan group of 89 former U.S. attorneys signed a letter last June warning that prosecuting misdemeanor unlawful entry cases would divert attention from more serious matters, such as terrorism and human trafficking.

The Justice Department repeatedly declined to comment, but when announcing the zero tolerance policy, Sessions said, “There must be consequences for illegal actions” and that the policy would be a deterrent. Hartzler is not so sure.

“It’s just a waste of resources to go after what are, in most cases poor, undocumented asylum-seekers who frankly don’t even always understand what the criminal court process is,” she says. “And as a result of not understanding that, it doesn’t have any kind of deterrent effect on them.”

Sessions also expressed confidence that local prosecutors were up to the job. But Hartzler says some trade-off can’t be avoided.

That may be reflected in the prosecutions data now. Using statistics provided by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, the ABA Journal found that misdemeanor unlawful entry prosecution rates in each of the five border districts did indeed pick up dramatically in fiscal year 2017 (which ran from Oct. 1, 2016, to Sept. 30, 2017) and continued to rise in fiscal 2018. In the Southern District of California, for instance, only 17% of its cases in 2017 were misdemeanor unlawful entry, but nearly 40% of them were in 2018.

NonMarijuana Prosecution rates

During the same period, prosecution rates for nonmarijuana drug felonies dropped. This category of offenses created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts includes all drugs other than marijuana—which the ABA Journal did not include separately because of the confounding effect of its legal status in some states—and offenses from simple possession to large-scale trafficking. Those rates dropped in every jurisdiction but the Southern District of Texas, where they rose from 11% of its cases in 2017 to just over 13% of them in 2018. In the Southern District of California, these prosecutions were 25% of its caseload in 2018 versus 32% in 2017.

The increase in unlawful entry cases is the expected result of zero tolerance—but it took place even though unlawful border crossings are at a historic low across the southwest border. CBP data shows that apprehensions declined from a peak of 1.6 million in fiscal 2000 to just under 304,000 in fiscal 2017, before rising to 396,579 in fiscal 2018.

Meanwhile, CBP statistics show that seizures of most drugs are up or steady, with fentanyl and heroin—both part of the opioid epidemic—growing slightly, a jump of just over 11,000 pounds of methamphetamine seized, and cocaine seizures returning to 2016 levels in 2018 after a 2017 spike.

Caseloads

Messages to four of the five border U.S. attorneys’ offices were not returned. However, USA Today obtained a memo last June suggesting that at least one U.S. attorney’s office was diverting staff members from drug cases to immigration.

The memo, from Assistant U.S. Attorney Fred Sheppard of the Southern District of California, warned border law enforcement agencies that the U.S. attorney’s office would decline to prosecute drug cases that weren’t finalized by the next morning, expressly noting this was because immigration cases “will occupy substantially more of our resources.”

Johnny Sutton, who was the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas from 2001 to 2009, says zero tolerance was business as usual in that district because it’s the home of Operation Streamline, an attempt under former President George W. Bush to prosecute every border-crosser. That effort started in Del Rio, Texas, and was widespread in the late 2000s but shrank to just parts of Texas and Arizona by 2014, according to a report from the Department of Homeland Security.

There are, however, signs that the situation may have changed. Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a project that compiles data on federal agencies from Freedom of Information Act requests, published a report April 2 with data suggesting that zero tolerance prosecutions are falling while CBP arrests are rising.

Across all five border districts, TRAC found that only about 38% of CBP arrests resulted in prosecutions in February of 2019, down from 50% in October of 2018. The largest declines were in the Southern District of California and the Southern District of Texas.

Prosecutions tend to drop around the holidays, but they didn’t pick back up with other offenses in January, says Jami Ferrara, who is a San Diego-based solo practitioner and serves as a panel representative for the Southern District of California’s Criminal Justice Act panel.

But Hartzler said a few weeks later that it looked like misdemeanor unlawful entry prosecutions were rising again.

She says she’d heard informally that the dip was related to Border Patrol agents being reassigned to deal with the recent increase in asylum-seekers. In mid-April, Hartzler said she had been led to expect a new surge of unlawful entry prosecutions.

But there are no guarantees.

“There are limited resources,” she says. “And inevitably, when you take those resources and you refocus them into misdemeanors—and not just misdemeanors, but a volume of misdemeanors—it takes away from the resources of the other more serious crimes.”

This article appeared in the June 2019 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: "Less than 'zero tolerance': Drug crimes prosecutions could be taking a back seat as the DOJ focuses on unlawful entry."