Documentaries are shaping public opinion and influencing cases

Image from Shutterstock.

Americans love a good comeback story, and until recently, R&B superstar R. Kelly was in the midst of one of the most unlikely yet successful second acts in recent memory.

Accused of filming himself having sex with an underage girl, the hitmaker was acquitted on charges relating to child pornography in 2008. Kelly largely emerged unscathed. The self-proclaimed “King of R&B” subsequently reclaimed his throne, working with A-list singers, touring and receiving multiple Grammy nominations. Although a 2017 investigation published in Buzzfeed accusing the singer, songwriter and producer of holding underage girls captive in a sex cult resulted in some backlash, including streaming services refusing to promote his songs, Kelly kept his record deal, and more important, his freedom. Kelly may not have been able to fly, like he believed in his famous song, but it sure seemed as if he could do almost anything else, including dodge bullets.

R. Kelly at a 2017 live performance. Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images.

But then the documentary Surviving R. Kelly premiered on Lifetime in January 2019. The six-part miniseries investigated the sex cult allegations while revisiting some older accusations against the singer, including those that led to the 2008 trial and his 1994 marriage to protegee Aaliyah, who was then 15 years old. Containing interviews with several former girlfriends, his ex-wife, family members and associates, the documentary succeeded in clipping Kelly’s wings. Days after the premiere, Georgia and Illinois opened criminal investigations and encouraged more victims to come forward. By the next month, Kelly had lost his record deal and been charged by the Cook County state’s attorney in Chicago with sex abuse. In July 2019, he got hit with federal sex abuse charges as well. At press time, he sits in a Chicago jail awaiting trial.

“I was so shocked that law enforcement got involved,” Surviving R. Kelly executive producer Tamra Simmons says. “We thought, ‘Maybe the families [of his accusers] could pursue legal action if and when they were reunited with their daughters.’ We knew there were certain laws that he had broken. What we didn’t know was if anyone would do anything about it.”

Gloria Allred of Allred, Maroko & Goldberg, who represents several of Kelly’s accusers, called the documentary “inspiring,” adding: “Courage is contagious, and the courage of those that spoke out inspired others. It made them realize, ‘I’m not alone. I didn’t realize he was doing this to others. Maybe I can speak out, too.’ When women break out of those chains of fear, many things are possible.”

Surviving R. Kelly is the latest in a string of documentaries that have made an impact—not just in terms of TV ratings, streaming figures or downloads. Popular documentaries such as Making a Murderer (2015), The Central Park Five (2012), Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996), The Staircase (2004) and podcasts such as Serial (2014) and In the Dark (2016) have helped shine a light on inadequacies in our criminal justice system, and in some cases have cast doubt on guilty verdicts, set wrongfully convicted individuals free, galvanized public opinion, and brought about structural and systemic reforms.

“Legal documentaries reflect the best of what media can do,” says Dan Abrams, chief legal affairs anchor at ABC News. “The influence these documentaries can have is enormous. They can sway public opinion. They can expose injustices, highlight things that have been buried and force action from people in power.”

On the flip side, Abrams cautions that some documentaries can blur the line between journalism and advocacy, giving them a veneer or presumption of legitimacy. “I think the danger can occur when documentarians become advocates and they don’t admit it,” he says. “They just pretend they review the evidence objectively.”

Sunlight

“Welcome to where time stands still. No one leaves, and no one will,” are the ominous opening lines to Metallica’s 1986 song “Welcome Home (Sanitarium).” Those words plus the eerie combination of minor and major chords in the song set the tone for 1996’s Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills and its two sequels, released in 2000 and 2011, respectively.

Tamra Simmons: “I was so shocked that law enforcement got involved.” Photo by Jesse Grant/Getty Images for Lifetime.

In the opening scene of the landmark 1996 film, it’s May 6, 1993, and the naked, mangled and disfigured corpses of three 8-year-old boys—Steve Branch, Michael Moore and Christopher Byers—are being fished from a drainage ditch in West Memphis, Arkansas. The sleepy, conservative town is rocked to its core, and residents—to say nothing of the devastated families of the victims—are determined to make the perpetrators of this heinous act pay.

When police arrest Jason Baldwin, Damien Echols and Jessie Misskelley Jr. and accuse them of being Satan worshipers who committed the murders as part of some dark ritual, the so-called West Memphis Three become the next Manson family.

Seeing the potential of another Helter Skelter-type of film, HBO sent filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky to West Memphis to shoot what they all assumed would be a dark tale of youth gone bad.

“We spent the first couple of months with the victims’ families, and that made us continue to believe that this documentary would be about these horrible teenagers who did these horrible things,” Berlinger says.

It wasn’t until the filmmakers got access to the defendants that they realized something wasn’t quite right. For Berlinger, whose credits also include Brother’s Keeper, a 1992 documentary he made with Sinofsky about a man wrongfully charged with his brother’s murder; and Wrong Man, a documentary series on the Starz network examining claims of wrongful incarceration, his doubts crystallized when he interviewed Baldwin, whom he described as a sweet, shy kid. “I kept staring at his little wrists,” Berlinger recalls. “They were so tiny, and if you believe the prosecution’s story, he’s the one that castrated Christopher Byers with a 10-inch serrated knife. I kept looking at his wrist and thinking there was no way he could have done that.”

Gloria Allred: “Courage is contagious, and the courage of those that spoke out inspired others.” Photo by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images.

After that, Berlinger and Sinofsky called HBO and told them they were having doubts about the defendants’ guilt. “They weren’t necessarily signing up for a wrongful conviction case. That genre didn’t exist the way it does now,” says Berlinger, mentioning 1988’s The Thin Blue Line, about the wrongful conviction of Randall Dale Adams for the murder of a police officer, as one of the few legal documentaries from that time period. “I thought they might tell us to come home, but [HBO executive Sheila Nevins] saw the potential and let us keep filming. The more we dug into it, the less it seemed like they did it.”

Unfortunately for the West Memphis Three, plenty of people believed in their guilt—including the jurors who decided their fates. The three were convicted despite a lack of physical evidence. For Misskelley, a 17-year-old with an IQ in the low 70s, his own words did him in: He confessed while being interrogated for approximately 12 hours without parental supervision or counsel. Misskelley later recanted, with his lawyer arguing that he had been coerced into a false confession due to his mental impairment, fear of the police and fatigue. Nonetheless, the judge sentenced Misskelley to life plus 40 years.

As for the other two, the prosecution focused on the occult, accusing the heavy metal-loving Baldwin and Echols of being Satanists. Despite their denials, Echols got the death penalty, and Baldwin was sentenced to life in prison.

“I believed in the criminal justice system and assumed everything would work itself out either before or at trial,” Berlinger recalls. “I had no real knowledge about the extent of wrongful convictions.”

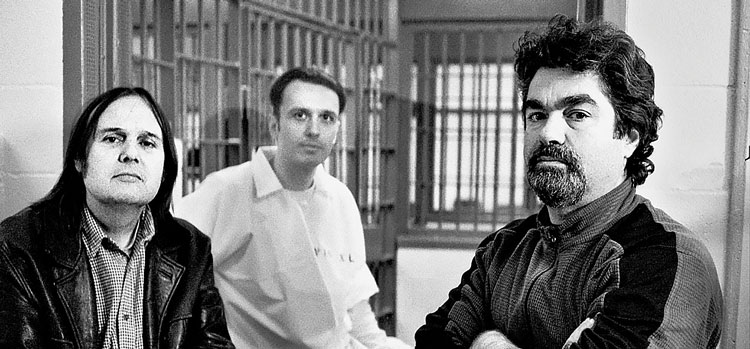

Filmmakers Bruce Sinofsky (left) and Joe Berlinger (right) visit Damian Echols (center) on death row in 2009. Photo by Bob Richman.

To handle the West Memphis Three’s appeals, Echols’ wife, Lorri Davis, hired Stephen Braga, then a partner at Ropes & Gray. Braga had just spent 13 years working pro bono on behalf of Martin Tankleff, a New York man convicted of murdering his parents largely on the basis of a false confession. After uncovering evidence pointing to another suspect, Braga got the conviction overturned, and the state chose not to retry Tankleff. Laura Nirider, co-director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law, served as co-counsel for Echols.

Braga’s research, which included watching Paradise Lost, left him feeling that the three had been railroaded. He also felt drawn to the case because of Echols, the charismatic leading star of the film. “When you see the scenes of him in the documentary, you can’t help but want to help this kid,” Braga says.

In fact, as a result of the documentary, many grassroots activists, including celebrities such as Johnny Depp, Eddie Vedder, Peter Jackson and his wife, Fran Walsh, worked with Davis’ Take Action Arkansas group to try to free the West Memphis Three. According to Braga, having celebrities on board helped raise both awareness as well as much-needed funds to pay for DNA tests and other investigations. Meanwhile, thanks to the internet, Arkansas Take Action began working with people across the globe, crowdsourcing evidence and theories. “By sharing information on the web, it leads to a better understanding of the failings of the case forensically, which then helps the lawyers out as well,” Braga says.

Their work paid off in 2010, when the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered the trial court to grant the three an evidentiary hearing to consider newly analyzed DNA evidence taken from hair samples that matched the stepfather of one of the victims. The following year, the state allowed the three to take Alford pleas, where they pled guilty while maintaining their innocence, and they were released after serving over 18 years in prison.

“The greatest thing to happen to the wrongful conviction movement is sunlight,” Braga says. “This documentary kept the case in the public spotlight. It ensured people would keep watching and led to the fairest result possible. Damien Echols has said that without this documentary, he would have been executed.”

Double-edged sword

Of course, not every documentary yields those kinds of results. Oftentimes, they underscore how difficult it can be to overturn guilty verdicts and expose the public to the challenges and complexities of the legal system.

For example, at press time, Adnan Syed remains in prison, serving life plus 30 years for the 1999 murder of his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee. The acclaimed 2014 Serial podcast, as well as the 2019 HBO film The Case Against Adnan Syed, cast doubts on his conviction and generated a tremendous amount of publicity. “I think that I could say, unequivocally, that Serial helped,” Syed’s attorney C. Justin Brown says. “For instance, we had an alibi witness that was the key to our argument, and we were unable to bring her into the fold. But after she heard how she important she was after listening to Serial, she came forward.”

The witness testified at a post-conviction hearing in 2016 that led Baltimore City Circuit Judge Martin Welch to grant Syed a new trial. However, the Maryland Court of Appeals overturned Welch’s order. “What was interesting was that the court of appeals had been sitting on their opinion for many months,” Brown says. “Then they issued their ruling denying us relief the Friday before the HBO documentary was to debut. I don’t believe in coincidence, and it’s impossible to know for sure, but I’ve always been and will be concerned that their opinion was adversely affected by the HBO documentary.”

A film about another high-profile case, Making a Murderer, debuted on Netflix in 2015 with 10 episodes spotlighting the 2007 murder convictions of Wisconsin residents Steven Avery and his nephew, Brendan Dassey. The bingeworthy documentary became a cultural phenomenon and was widely covered in the media.

Photo by Netflix

“I think it’s helped and hurt—I’m not sure where it nets out,” Avery’s co-lead trial attorney Dean Strang says of Making a Murderer. On the one hand, Strang points out that the documentary has raised awareness of the case and—like Paradise Lost did for the West Memphis Three—helped Avery’s post-conviction counsel by inspiring many people to crowdsource evidence and sift through transcripts, among other things. “It’s also inflamed those who think Avery is guilty and has caused the state to take an ever-more defensive crouch as to Steven’s efforts to vacate the conviction,” Strang says. “And I think it probably has some of that effect on the judiciary. When operating under spotlight, judges tend to work ever harder to preserve the status quo.”

Perhaps the most memorable scenes in the first season involve Dassey, a quiet, shy 16-year-old with an IQ in the low 70s. Using video from his March 1, 2006, police interrogation, the fourth episode showed Dassey, alone and without counsel or parental supervision, lounging slightly in a loveseat inside a police interrogation room and looking half asleep while being subjected to hours of questioning from two experienced detectives. Eventually, Dassey confesses to helping his uncle rape, murder and then mutilate the corpse of 25-year-old photographer Teresa Halbach—a confession he’d later recant. After he’s finished, essentially giving the police the statement prosecutors would use to send him and his uncle to prison, he puts his hands on his head as if he can’t believe what he’s just done. “They got to my head,” he later explained to his mother.

Laura Nirider: “I have represented people who have falsely confessed for years.” Photo by Phil Goldman Photography

“I have represented people who have falsely confessed for years,” says Nirider, Dassey’s post-conviction attorney. “I have found it difficult to convince people that it happens. But when people saw that video of Brendan and heard the techniques used on him and saw how he reacted, then it becomes intuitive and changes the narrative into something everyone understands.”

Nirider was planning to become a corporate lawyer before taking Northwestern law professor Steve Drizin’s class on wrongful convictions (the two are currently co-directors of the Center on Wrongful Convictions) and working on Dassey’s appeal as a third-year law student. She credits both Making a Murderer and Paradise Lost for helping raise awareness of false confessions and how they can send the wrong people to prison. The outcry over her client’s treatment resulted in a massive clemency campaign for Dassey in late 2019, including an online petition signed by tens of thousands of people worldwide, as well an open letter to Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers signed by 250 lawyers, politicians and people who have given false confessions.

However, all of their efforts were for naught because Evers declined to grant Dassey clemency. “That was a difficult moment because of the global groundswell of support that there was, and is, behind Brendan,” says Nirider, who notes Evers followed the advice of his pardon advisory board. She hopes a direct appeal to the governor, a former educator, will be more successful.

Advocacy or accuracy?

Obviously, documentaries only present a fraction of the complete overall narrative. As Berlinger points out, he and Sinofsky shot over 200 hours of footage for the first Paradise Lost film, which clocked in at around 2½ hours. Even multiepisode documentaries such as Making a Murderer capture only a small fraction of the entire story.

“No documentary film can ever be the complete, objective truth of any situation,” Berlinger says. “It’s a heightened reality because of the process of filmmaking. You have to trust the filmmaker to give you the emotional truth, not the literal truth, of the situation.”

Madeleine Baran: “There wasn’t something we had to prove or needed to be true.” Photo by Caroline Yang for APM Reports.

In fact, Abrams has been critical of Making a Murderer, arguing the documentary left out or overlooked facts in order in order to advocate for Dassey and Avery.

For instance, Abrams says any rational police officer would have considered Avery a prime suspect due to the fact that he was the last person to see the victim alive, her remains and car were found on his property, and her car key was recovered in his home, among other things. Additionally, he takes issue with the documentary’s theory that the police set up Avery at the same time they ignored or mishandled key evidence, comparing it to O.J. Simpson’s defense.

When it comes to Dassey, however, Abrams agrees that he is probably innocent. Like many others, he watched the tapes of Dassey’s interrogation and believes his lack of sophistication and understanding of his situation allowed him to be tricked, manipulated and coerced into giving a false confession.

“I think the most important thing is transparency—accuracy,” Abrams says. “Unfortunately, it’s not that I think these major documentaries are getting facts wrong on a regular basis. Most of them get them right. It’s just a question of what facts do they highlight, and what do they omit?”

The 2018 podcast In the Dark by APM Reports—the investigative arm of American Public Media—examined the case of Curtis Flowers, a man tried six times for a 1996 quadruple murder in Mississippi. Flowers has been convicted four times, but each conviction was reversed on appeal due to prosecutorial misconduct. Lead reporter Madeleine Baran tried to maintain accuracy and transparency throughout the entire process, pointing out: “We did not go into the reporting for this piece to try to exonerate him. There wasn’t something we had to prove or needed to be true. If I was a lawyer or something like that, it would be different.”

Flowers was convicted for a fourth time in 2010 and sentenced to death. The U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 overturned his sentence after finding that the prosecutor systematically excluded black jurors in violation of Batson v. Kentucky (1986) and ordered a new trial. In the Dark’s reporting was cited in the briefs.

Michael Peterson (left) gets a congratulatory embrace from attorney David Rudolf (right). Photos by D Dipasupil/Getty Images; Netflix.

In 2019, Flowers was granted bail with his defense lawyers citing In the Dark numerous times—particularly when it came to uncovering evidence incriminating another possible suspect. Baran recalls being stunned that the judge seemed so sympathetic to Flowers, even going so far as to call him a “person with a significant chance of acquittal.”

“That seemed astonishing considering he’d always been so receptive to the state and their arguments,” Baran says. “Instead, he seemed aggravated with the state because he didn’t have the whole story.” Flowers is currently free on bail while the state (with the prosecutor recused) decides whether to try him for a seventh time.

On the other hand, when French filmmakers decided to make a documentary examining the murder trial of accused wife-killer Michael Peterson of Durham, North Carolina, there was no pretense of impartiality. The crew agreed to work for the defense to get access to the defendant, a condition Peterson’s lawyer David Rudolf insisted on as a means to protect attorney-client privilege. As part of the deal, the crew was required to send their dailies to France every night so they couldn’t be subpoenaed by the prosecution. The resulting documentary was 2004’s The Staircase, which originally aired on television networks and was so popular that it spawned two sequels. It was rereleased on Netflix in 2018.

Rudolf always had subscribed to the belief that defendants should keep their mouths shut until trial, but his client saw the potential of the documentary immediately. “Michael believed the powers that be that existed in Durham would be out to get him,” Rudolf says. “He thought having a documentary film crew in town for the trial would perhaps temper the zealousness of those out to get him.”

Peterson was convicted, but he was granted a new trial in 2011 after a judge found that a forensic expert who testified for the prosecution had given false and misleading testimony while exaggerating his credentials. Peterson took an Alford plea in 2017 and was released. While the original documentary left the question of Peterson’s guilt open because it centered entirely on his case and his lawyers, it resulted in a wave of sympathy and support. In one of the later documentaries, Peterson even gets emotional and hugs members of the film crew for helping him secure a new trial.

Remembering the forgotten

When The Central Park Five—directed by Ken Burns, his daughter Sarah and her husband, David McMahon—was released in 2012, the five men who were convicted as teenagers for the brutal rape and attempted murder of a jogger in Central Park already had been exonerated. However, they had largely been forgotten about and had

only been able to tell their side of the story in court pleadings and proceedings. When they filed a lawsuit against the city of New York in 2003 for malicious prosecution and discrimination, among other things, it seemed as if the city already had moved on.

The Central Park Five: (from left to right) Korey Wise, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana and Yusef Salaam. Photo by Antonio Perez - Pool via Getty Images.

“We tried to get some sort of public awareness of this case,” says David Kreizer, a New York attorney who represented Korey Wise, one of the Central Park Five. “We tried calling every news outlet, and they told us it was old news.”

The documentary, however, put the issue back squarely in the public eye, and Burns himself told the New York Times in 2012 that his goal was to get the city to settle. Two years later, the city finally settled with the Central Park Five for $41 million.

Time will tell what happens to both R. Kelly and his accusers. For his part, Kelly has denied all of the allegations against him. In one of his only public appearances before being imprisoned, Kelly condemned Surviving R. Kelly and told CBS News’ Gayle King that he was being railroaded. “They are lying on me,” he said, breaking down in tears while categorically denying he’s ever had sex with underage girls and maintaining that he would have to be pretty stupid to start a sex cult considering his past. His attorney, Steven Greenberg, did not respond to a request for comment.

For Surviving R. Kelly executive producer Simmons, the documentary already has helped some of his accusers start the healing process while hopefully providing a beacon of hope for future generations. “There were so many who were scared to speak out against this man because they weren’t sure they’d be heard,” says Simmons, who, along with her team, released Surviving R. Kelly Part II: The Reckoning, which dealt with the fallout from the first part—both for Kelly and his accusers—in January 2020. “As an African American woman, I wanted to make sure my daughter and all our daughters knew our voices did matter.”

This story was originally published in the August-September 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Reel Power: Documentaries are shaping public opinion and influencing cases.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.