Do origin stories define or help refine constitutional interpretation?

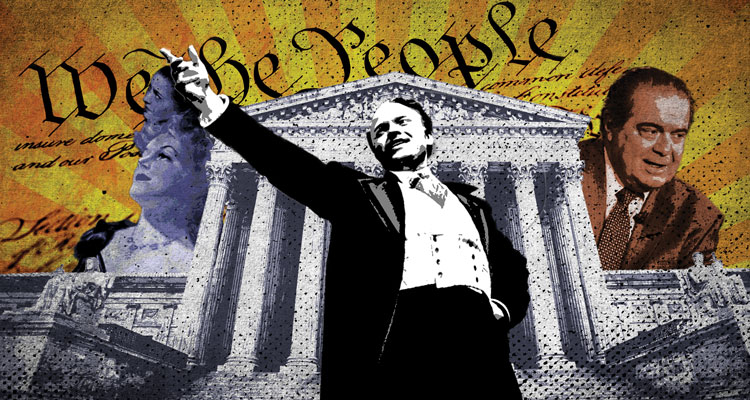

Locked down at home during the coronavirus pandemic, I watched Orson Welles’ 1941 film, Citizen Kane.

The inciting incident of Welles’ masterpiece is the title character’s death. On his deathbed, Kane utters “Rosebud” with his final breath. Is that word somehow a key that unlocks his past? Is it a clue revealing Kane’s identity and the meaning of his complex and contradictory life?

For me, a law professor, Welles’ enigmatic scene provides a cinematic analogue evoking the U.S. Supreme Court’s endless quest for the meaning behind crucial words from the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, locked away in foundational moments from long ago.

All lawyers are storytellers. And Supreme Court justices are not exceptions. Outcomes in constitutional law are typically predicated upon the stories the justices tell—interpretations of foundational “origin stories”—that shape understandings of the law and who we are as a people. Origin stories—similarly referred to as “backstories” in pop culture—build upon myth and history, providing crucial narrative framing for constitutional interpretation, often predetermining constitutional meanings. Hundreds of years later, the question remains whether to interpret America’s original texts as “living documents” or as “sacred texts” handed down as if from a higher authority.

The late visionary Yale law professor Robert Cover observed, “No set of legal institutions or prescriptions exists apart from the narratives that locate it and give it meaning. For every constitution there is an epic; for each decalogue a scripture. Once understood in the context of the narratives that give it meaning, law becomes not merely a system of rules to be observed but a world in which we live.”

For Cover, words lose their meanings when they are not located within a narrative tradition of interpretation.

Perhaps origin stories are even more important than Cover suggests. Constitutional cases are built upon shared historical creation myths. Without some origin story, the Constitution and Bill of Rights are merely broken shards of language spinning in the ether—akin to Kane calling out “Rosebud” with his dying breath.

Originalist’s interpretation

Our greatest judicial proponent of a purportedly narrative-free jurisprudence was the late Justice Antonin Scalia. His “originalism,” or “textualism,” in its most dumbed-down form appeared to strip narrative context from constitutional interpretation.

For Scalia, constitutional meanings resided in the words themselves and in “reasonable” acontextual interpretations of those words, without the reader’s subjective storytelling inviting an ever-changing interpretive lens of politics and contemporary values. He didn’t support the idea of a living Constitution; its meanings were fixed and did not morph across time.

As Scalia said, “The originalist at least knows what he is looking for: the original meaning of the text. Often—indeed, I dare say usually—that is easy to discern and simple to apply.” He added, “What I look for in the Constitution is precisely what I look for in a statute: the original meaning of the text, not what the original draftsmen intended.”

Scalia further observed, “The Constitution that I interpret and apply is not living but dead—or, as I prefer to put it—enduring.”

Landmark case revisited

Does theory insulate Scalia from the imaginative grip of origin stories? Of course not.

For example, in District of Columbia v. Heller, Scalia famously struck down provisions of the Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 as unconstitutional, ruling that District of Columbia residents possessed a Second Amendment right to own and keep handguns for self-protection.

Scalia begins with a grammarian’s counterintuitive analysis of the words of the Second Amendment, breaking the text into two discrete and detachable provisions: a prefatory clause (he called it a “prologue”), separate from a second operative clause and not limited by the purposes clearly announced in the initial provision.

But then Justice Scalia time travels over the barriers of earlier and contradictory Supreme Court precedents, heading back into the world of our constitutional forefathers at the moment of the birth of our nation.

Scalia arranges select narrative fragments to fit his core narrative theme—the founders sought to preserve individuals’ common-law right of self-defense in an ever-dangerous land—concluding that current District of Columbia residents preserve their Second Amendment right to possess handguns in their homes for personal protection.

So what is Scalia’s underlying “default” origin story? Perhaps, as Cover suggests, it is a biblical story where textual meanings are revealed prophetically by an omniscient narrator imbued with force of law.

Counterstory

In his 2015 book, The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution 1783-1789, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Joseph J. Ellis argues that the Constitution and Bill of Rights were never intended as sacred texts with fixed meanings designed to withstand time.

According to the author’s interpretation, the founders made the Constitution purposefully vague, considering it a living document with malleable words to be perfected over time and fitting the unfolding experiences of the people of our new nation.

In Ellis’ version of our origin story, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights that followed were a second Revolution of sorts, a veritable coup. Political elites “conspired” to replace a state-based confederation with a federal government “that claimed to speak for the American people as a collective whole.”

The plot is instigated by four remarkable and heroic protagonists: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison, with the help of several important co-conspirators.

After enlisting Washington’s crucial support, these brothers in arms struggle to preserve the victory of the Revolution and push the country—against its backsliding impulses and away from weak Articles of Confederation—toward a strong and centralized federal authority guaranteed by a Constitution, further insured by the Bill of Rights.

As Ellis puts it, these Founding Fathers were politically motivated strategists and actors-in-consort who “diagnosed the systematic dysfunctions under the Articles, manipulated the political process to force the calling of the Constitutional Convention, collaborated to set the agenda in Philadelphia, attempted somewhat successfully to orchestrate the debates in the state ratifying conventions, then drafted the Bill of Rights as an insurance policy” that transformed “the people” into an “us” rather than a “them.”

Drawing upon a trove of recent historical materials, he crafts a marvelous origin story that, like Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton, also fits our times.

Minor subplot

According to Ellis, Madison was the primary architect and original draftsman of the Bill of Rights, even though he “did not really think the Constitution needed a bill of rights.”

Madison’s Bill of Rights was never intended to “become enshrined as the semi-sacred creedal statement of America’s core political values,” Ellis writes. Indeed, its purposes “were neither constitutional nor philosophical but political.”

Ellis says we tend to regard the Bill of Rights as a “secular version of the Ten Commandments,” but this wasn’t the drafters’ intent—especially Madison’s. The Bill of Rights was added to secure ratification after opponents were “pushing” for a second convention with hopes of passing a revised, weaker version of the Constitution closely based upon the Articles of Confederation. Opponents of ratification wanted clearer protections from government intrusion into their private lives. Madison “took the lead” in addressing these concerns with a Bill of Rights.

As to the Second Amendment, Madison’s intention was simply to “assure those skeptical souls that the defense of the United States would depend on state militias rather than a professional federal army.” This would uphold states’ and individuals’ rights against any potential tyranny borne of federal authority.

Our ‘living Constitution’

At the end of the book, Ellis quotes Jefferson: “Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched. They ascribe to the preceding age a wisdom more than human. … But I know also that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.”

To this Ellis adds: “One of the few original intentions they all shared was opposition to any judicial doctrine of ‘original intent.’ To be sure, they all wished to be remembered, but they did not want to be embalmed.”

Constitutional storytelling is irresistible for Supreme Court justices and for historians, too. Of course, Scalia’s and Ellis’ origin stories are inapposite and fundamentally irreconcilable. Which one is true? Alas, we will never know.

Ellis’ story certainly has verisimilitude. But Scalia’s forceful textualist vision has legal authority and prevails—at least with the five avowed originalists currently sitting on the Supreme Court.

We employ origin stories and creation myths about constitutional law to reveal who we were then, to tell us who we are today and who we will become tomorrow.

This story was originally published in the Feb/March 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Origin Stories: Do they define or help refine constitutional interpretation?”

Photo of Phillip Meyer by Emily Potts.