Dead Precedents: The Justices Overrule, But They Often Do So Stealthily

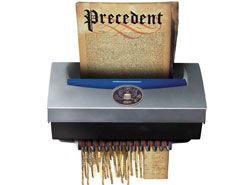

Illustration by Viktor Koen

If the U.S. Supreme Court is going to overrule a precedent, wrote an exasperated Justice Antonin Scalia four years ago, then “in any sane world” just go ahead and do it. And say so. Overruling is indeed a “serious undertaking,” Scalia wrote in Hein v. Freedom from Religion Foundation Inc. But “honoring stare decisis requires more than beating [the precedent] to a pulp and then sending it out to the lower courts weakened, denigrated, more incomprehensible than ever, and yet somehow technically alive.”

Instead of “eras[ing] this blot on our jurisprudence” the court has “simply smudged it,” Scalia wrote in disdain.

Scratched-out precedents are becoming frequent as the high court has made a habit of stealth overruling, finding ways to avoid express rejection of a precedent by instead gnawing away at old cases without officially declaring them dead.

“The hallmark of stealth overruling,” says New York University law professor Barry Friedman, “is that the justices are perfectly aware that they are overruling, but hide the fact that they are doing so.”

Instead, the court has sneaked through opinions that denude earlier cases of effectiveness, yet leave them barely alive.

Or a justice will have planted a time bomb in a current opinion, hoping a friendly lawyer or legislator will later spark the fuse, exploding the precedent into constitutional oblivion.

The tactic “obscures the path of constitutional law from public view, allowing the court to alter constitutional meaning without public supervision,” wrote Friedman in “The Wages of Stealth Overruling (with Particular Attention to Miranda v. Arizona),” a paper published last fall by the Georgetown Law Journal.

TIME BOMBS

Take Hein, for example. a religious rights group said taxpayers had standing to sue the executive branch for spending on faith-based initiatives. But a 5-4 plurality opinion by Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. held otherwise and carved out a narrow distinction from a 1968 case that permitted taxpayers to sue Congress.

“We do not extend [the precedent case], but we also do not overrule it,” Alito wrote. “We leave [it] as we found it.”

Scalia concurred; but for a strict textualist, beating about the bush was too much. “We must surrender to logic and choose sides,” Scalia said: Either apply the precedent or repudiate it.

Scalia “knows what they’re up to and would rather that they either just overrule or stop pretending they’re not doing just that,” says University of Alabama law professor Paul Horwitz, who reviewed Friedman’s article on the Jotwell website.

And then there are time bombs. In 2007’s Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. Inc., the high court held 5-4 that a female manager at an Alabama tire plant filed her pay discrimination claim too late under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The court, in a ruling also by Alito, said the equal-pay lawsuit was barred because the statute of limitations began the date the pay was agreed upon, not the date of the most recent paycheck.

In dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg criticized the opinion, then added: “Once again, the ball is in Congress’ court … to correct this court’s parsimonious reading of Title VII.” Two years later, Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which restarted the 180-day statute of limitations with each new check.

ACTIVELY MINIMALIST

Stealth overruling is not new; one of the craftiest time bomb planters was Justice William J. Brennan Jr. However, with the recent outcry over judicial activism, the court under Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. has become skittish about portraying itself as too eager to upset the continuity of law.

“It is inconsistent with the idea of judicial minimalism,” says Richard L. Hasen, a professor specializing in election law who is visiting at the University of California at Irvine School of Law. “It is the intention that judges are not making law but finding law.”

Friedman adds, “Those are the circumstances under which [the recent justices] took their seats.” Stealth overruling is a “sophisticated game to make their decisions appear less activist.”

Besides avoiding judicial activism—or at least the appearance of it—the justices have other reasons to overrule by stealth.

“It just might be that there are more existing precedents” that this conservative court wants to be rid of, suggests Hasen, author of a forthcoming law review article on the subject. Look at “where the law was compared to the justices’ idea of where it should be.” Says Friedman: It’s “not just the list of precedents, but that now the court has the votes.”

Hasen finds other ways the Supreme Court can nibble away at precedent: anticipatory overruling, where the court says it intends to overrule in a future case; and invitations, where a justice invites a litigant or Congress to press for overruling.

Alito is a prominent invitation sender. Although the justice insists on the protocol of being asked to overrule, Hasen says, Alito wastes little time in extending the offer.

In the court’s 2007 ruling in Wisconsin Right to Life v. Federal Election Commission, Alito questioned limits on corporate election spending. “If it turns out,” Alito wrote, that the standard “impermissibly chills political speech, we will presumably be asked in a future case to reconsider the holding” on the constitutionality of the McCain-Feingold campaign law.

After being petitioned to do so, the court, in its controversial 2010 case Citizens United v. FEC, overruled precedents that upheld parts of the McCain-Feingold law.

Citizens United shows the uproar when the court expressly overrules. While the court had steadily shaved off parts of McCain-Feingold, Citizens United outright discarded limits on corporate and union campaign contributions.

In so doing, Roberts, accompanied by Alito, justified his viewpoint in a concurrence. “Stare decisis is a doctrine of preservation, not transformation,” Roberts wrote. “It counsels deference to past mistakes, but provides no justification for making new ones.”

The political outcry was immediate. President Barack Obama criticized the decision in his 2010 State of the Union address, as did members of Congress and the academy. The Roberts court “is really sensitive to” express overruling, Friedman says. “Citizens United was proof certain of that.”

On the other hand, says Friedman, the evolution of progeny based on Miranda v. Arizona shows how gradual stealth overruling can eventually whittle the major case to meager facts.

Since the 1966 ruling required officers to inform suspects of their constitutional rights before questioning, the conservative wing has steadily slammed the decision. In three cases last term, the court ruled that a suspect’s request for a lawyer is good for only 14 days after release from custody, that police do not explicitly have to tell suspects they have a right to counsel during an interrogation, and that criminal suspects must unambiguously announce to police that they wish to remain silent. In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor lamented that the court was “turn[ing] Miranda upside down.”

Ultimately, Friedman says, Miranda’s stealth overruling has given law enforcement the Supreme Court’s message “not to take Miranda seriously.” And, he says, it has “reduced the lower courts to a group of post hoc rubber-stamping magistrates,” letting cases go because judges won’t be reversed.

‘THE OBFUSCATOR OF LAST RESORT’

So far this term, experts point to Michigan v. Bryant as a case where the court is starting to carve away slices of its confrontation clause jurisprudence. The court said a wounded crime victim’s statement to police identifying the person who shot him may be admitted as trial evidence if the victim dies before trial, because the interrogation’s purpose was to enable police to deal with an ongoing emergency.

In dissent, Scalia said, “the opinion distorts our confrontation clause jurisprudence and leaves it in a shambles. Instead of clarifying the law, the court makes itself the obfuscator of last resort.”

Should stealth overruling continue, Friedman says, the court will continue to be “confusing the law,” leaving others to wonder about “which way the precedents are going.”

“There were times when the court knew it was acting boldly, felt it could afford to, and didn’t hesitate to grasp the nettle—for better and for worse,” Horwitz says. “In a media-heavy age, the court is so aware of being watched that it’s especially loath to act with what might be seen as a heavy hand. So we’re likely to see them acting in a way that moves incrementally toward whatever their broader goals might be.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.