The tragedy of ‘deaccessioning’ books from university libraries

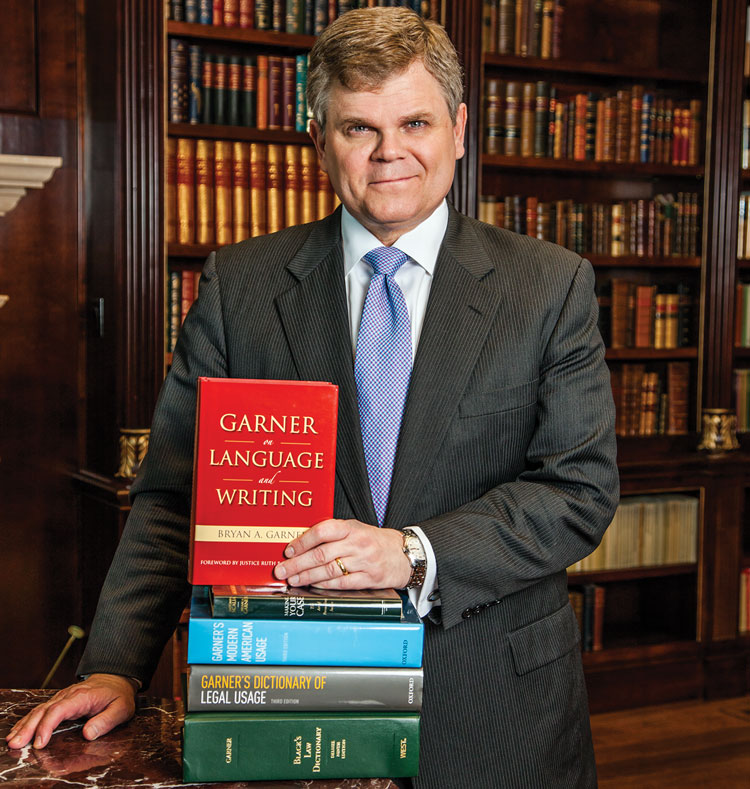

Photograph of Bryan Garner by Terri Glanger; ©WALKNBOSTON CC

Scenario No. 3: A Texas practitioner is briefing an appeal for a woman claiming to be the common-law wife of a man who has died in an industrial accident. Of course, the three elements of common-law marriage are well-known in the 10 jurisdictions that recognize it: an agreement to be married, cohabitation for some period, and a “holding out” as spouses to the community at large. The first two are easily established here, so everything hinges on the holding-out element. Hence our practitioner wants to know what Texas courts have held on the subject.

Westlaw searches mostly produce cases that merely iterate the three elements of a common-law marriage.

A colleague tells our practitioner friend he ought to look at Joseph W. McKnight’s annual surveys of family law. Dubious, the practitioner finds a law library that holds print copies of the SMU Law Review to discover that each year from 1970 to 2016, McKnight authoritatively analyzed the appellate decisions in Texas relating to family law. Starting with 2016, our friend goes back year by year in the bound volumes, soon discovering that McKnight began each yearly update with discussions of important holdings relating to common-law marriages.

Much to the practitioner’s surprise, McKnight calls them “informal marriages” because “common-law marriage” is something of a misnomer: It might have been a common-law doctrine at first, but today a statute authorizes these marriages—and informal marriage is the more accurate term. Our friend realizes that his Westlaw searches have missed half the cases—an oversight he soon cures.

From McKnight’s discussions, the practitioner also discovers that half the cases he’s found have been overturned, disapproved or otherwise superseded by later cases. Some of these he would have found later when shepardizing, but not immediately or clearly the reasons why.

Soon, with the help of a junior colleague, the practitioner is categorizing the indicia of holding out and finds eight: (1) spousal introductions, (2) a stepparent–stepchild relationship, (3) published displays such as funeral pamphlets, (4) outward displays such as mutual tattoos, (5) shared debts and financial responsibilities, (6) a shared last name, (7) general community perceptions and (8) formal documents such as tax returns and insurance documents. His client satisfies seven of the eight.

Nobody, including McKnight, has ever said there are eight indicia. That’s original. But McKnight has led the practitioner to 35 cases illustrating those indicia, and computer searches have yielded 15 more cases. Without the McKnight surveys, the practitioner would have been flailing about in a morass of case law, without authoritative guidance to the important holdings.

By flipping from volume to volume in the books, he has accomplished in two hours what he could not have done nearly as efficiently, if at all, on the computer.

The Upshot: Book research is well-nigh irreplaceable to the skillful researcher. It can’t, and shouldn’t, be fully superseded by online research, which of course has its own splendors but also its own limitations.

So it’s disheartening to hear what’s happening to our libraries. A lead Associated Press article on Feb. 7 reports that “as students abandon the stacks in favor of online reference material, university libraries are unloading millions of unread volumes in a nationwide purge.” Some books are being hauled off to permanent storage sites; others are being sold en bloc to used-book dealers; and still others are being thrown into dumpsters.

Given that half the library collection at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania has been “uncirculated for 20 years or more,” university administrators decided to purge 170,000 volumes. “Bookshelves are making way for group-study rooms and tutoring centers, ‘makerspaces’ and coffee shops,” the article reports. Oregon State University librarian Cheryl Middleton, president of the Association of College and Research Libraries, is quoted as saying, “We’re kind of like the living room of the campus. We’re not just a warehouse.”

Traditional scholars are outraged. One calls this jettisoning of books “a knife through the heart.” He’s right, of course.

Now back to our three scenarios. Are they realistic?

Absolutely. They’re real. They’re lightly fictionalized self-depictions. The first describes me in 1980, the second me in 2014, the third me in 2017.

Is there any good news here? Only for book collectors and used-book dealers: Among the heaps are some treasures. For example, in recent years I’ve obtained many rare books that have been “deaccessioned” from university libraries—including some bearing the signatures of the likes of Learned Hand and Harlan Fiske Stone.

Although it’s nice having them, I know that it was a travesty of librarianship that led to my acquisitions. Worse than a travesty, it’s a tragedy.

Bryan A. Garner, the president of Dallas-based LawProse Inc., was originally a Shakespearean scholar, then a legal lexicographer, then a writer on jurisprudence—as well as a book collector. He has an appellate-consulting practice. His most recent book is the memoir Nino and Me: My Unusual Friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Booking the Dumpster: The tragedy of 'deaccessioning' books from university libraries".