Lawsuit against Dave & Buster's challenges reducing employee hours to avoid health insurance mandate

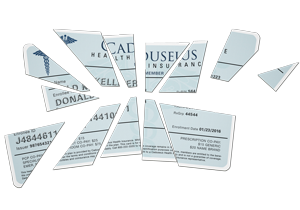

Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster

Renard Sanders remembers the day in 2013 when his bosses at Dave & Buster’s in Duluth, Georgia, called an early-morning meeting.

It was picture day, a Saturday when the entire staff would smile together outside of the building for a group photo.

But as they gathered inside afterward, management made several announcements. “They told us they were cutting our hours, so that they wouldn’t have to offer insurance, that they were taking everyone off of full time except a few people in management,” says Sanders, who had started out busing tables and later moved on to the cleaning crew during his two years with D&B. His shift was cut by 10-15 hours per week.

Sanders, 35, and his co-workers at the video-arcade and restaurant chain were not alone.

At about the same time at the company’s Times Square location in New York City, Maria de Lourdes Parra Marin, a cancer survivor, heard the same news.

Employed full time since August 2006 as a line cook, preparing items from D&B’s “Fun American New Gourmet” menu, Marin learned that she and most of the 100 or so Times Square workers soon would be part time. Her hours slid to just seven for a week.

A native of Mexico, Marin, 53, didn’t know where to turn. At her age, “it is not easy to have a new job,” she says, especially in the kitchen of a restaurant typically dominated by young men.

That’s when—with the help of her 23-year-old nephew Edwin Olivo, an aspiring law student—Marin contacted the National Employment Lawyers Association. This ultimately led to the first class-action suit in the nation to claim that the actions an employer took to reduce health care costs and the number of full-time employees violates the Employee Retirement Income Security Actof 1974.

A NEW KIND OF CLAIM

What makes the case unique is the allegation that D&B made the changes to avoid complying with then-forthcoming mandates under the Affordable Care Act. The case is being watched by employers nationwide who are under the same requirement to provide health benefits or face a possible financial penalty.

At the time the suit was filed in May 2015, the attorneys estimated D&B’s actions had affected about 10,000 workers at 72 locations nationwide. Certification as a class action suit is another step in the process that has not been reached in the case, which is before U.S. District Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein in the Southern District of New York.

ERISA prohibits interfering with a worker’s ability to “exercise any right to which he is entitled under the provisions of an employee benefit plan.”

The complex ACA has both employer and employee insurance mandates. The ACA mandates, with some variations, that employers who have more than 50 workers provide health coverage for those who clock 30 hours on average per week or pay a penalty if the worker uses a federal subsidy to obtain insurance through an exchange. The penalties, which also can be imposed on individuals who remain uninsured, went into effect in January 2015 after a one-year delay.

In the past, typical ERISA cases have alleged workers were let go or otherwise induced to resign after making costly claims on an employer’s health plan or being terminated just prior to retirement with a loss of vested pension benefits, says William Frumkin, a partner with Frumkin & Hunter in White Plains, N.Y., who is among the attorneys representing Marin.

In Frumkin’s view, the ACA ushered in a new claim under ERISA, and by altering workers hours, employers were violating the prohibition in effect in the act. Instead of letting them go, so they no longer would be eligible, D&B reduced hours at locations across the country, he says.

“This is really the crux of our case,” he adds, alleging that D&B took this action so that “ACA-compliant benefits didn’t have to be provided.”

Frumkin says he hopes the suit will deter others from acting to reduce worker hours in a way that causes them to lose health coverage.

There’s no doubt the suit is being watched because it is the first one of this type, says Joseph Lazzarotti, a principal in the Morristown, New Jersey, office of Jackson Lewis, which exclusively represents management in employment law issues and cases.

GUIDANCE NEEDED

But Lazzarotti doesn’t think it’s a slam dunk for the plaintiffs. He says the ACA employer mandate has created a “perceived right” to health benefits, the validity of which Judge Hellerstein will have to decide, along with whether the affected workers were a “targeted” class.

He agrees that the issue needs to be clarified. Having fewer full-time workers is “a way to try to minimize exposure and not take on significant costs that you didn’t take on before,” he says of employers. “It is something employers need some guidance on, so they can manage their businesses.”

D&B’s attorneys did not respond to email and phone requests for comment. In their responses to the complaint and in their unsuccessful motion to dismiss the suit, Daniel J. Beller, Daniel J. Leffell and Maria H. Keane with Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, argued, among other points, that the ACA “provides no right to participate in an ACA-compliant health plan, to either full- or part-time employees.”

But, to Judge Hellerstein, “the critical element is the intent of the employer—proving the employer specifically intended to interfere with benefits,” he wrote in his denial of D&B’s attorneys’ motion to dismiss the case.

He ruled that Marin’s legal team “sufficiently and plausibly alleged this element of intent” and had “sufficiently pled that the employer had acted with an ‘unlawful purpose’ when taking an adverse action against her.”

Among the D&B statements cited by the judge were those allegedly made during the meeting that Marin attended, including that compliance with the ACA would cost Dave & Buster’s as much as $2 million, and that, to avoid that expense, the company planned to reduce the number of full-time employees to about 40 total from more than 100.

Judge Hellerstein also rejected D&B’s argument that Marin couldn’t make a claim “to benefits yet to be accrued,” namely the richer ACA-mandated benefit package, pointing out that Marin also lost the coverage in effect at the time. Hellerstein also said that Marin’s claim “for lost wages and salary incidental to the reinstatement of benefits” could move forward.

MEDICAL HARDSHIPS

All of this is welcome news to Marin—and to Sanders, who is eager to join the suit and did not know about it until he was contacted by the ABA Journal. The loss of insurance and pay led to a series of hardships for him, Sanders said, and he returned to Florida, where he currently is unemployed.

Marin has searched, unsuccessfully, for full-time employment that would give her insurance coverage. She has a second job and gets medical care at a local hospital-affiliated clinic that charges her income-based fees. Marin regularly takes medications to keep in check her high blood pressure, to keep her thyroid functioning and to prevent a recurrence of breast cancer.

Yet, she has “stayed strong,” as her nephew Olivo put it, and is hopeful that her hours and benefits will be restored.

It is not right, Marin says, that she and the other workers committed years to D&B, and then, “one day, in one meeting, they say, ‘I’m sorry, everybody, but we don’t have money to pay your benefits.’”

By bringing the suit, she says, “I believe I am doing the right thing.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Cutting Coverage: Lawsuit against Dave & Buster’s challenges reducing employee hours to avoid insurance mandate.”

Theresa Defino is an editor at Atlantic Information Services.