June 19, 1972: Curt Flood loses 'reserve clause' challenge

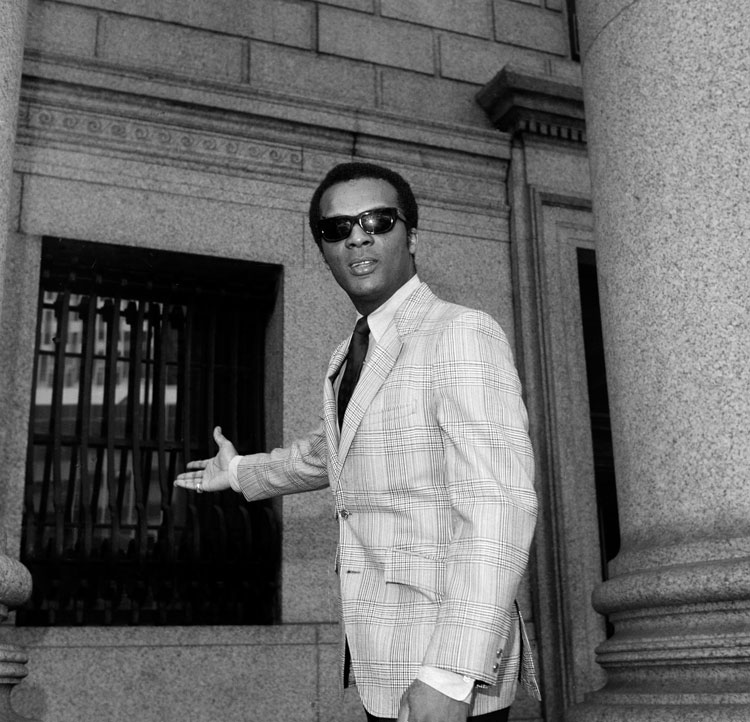

Curt Flood pauses on June 1, 1970, in front of Federal Court in New York City, where his legal challenge of baseball’s reserve clause resumed. Flood balked at being traded by the St. Louis Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies and sued organized baseball for $3 million in damages. Photograph by AP Photo.

In October 1969, the St. Louis Cardinals completed a blockbuster trade with the Philadelphia Phillies. The seven-player deal included two major stars at the pinnacle of their careers: Dick Allen of the Phillies and Curt Flood of the Cardinals.

Allen—a former rookie of the year—had hit 32 home runs the prior season. Flood, a center fielder and .300 hitter, was a two-time World Series champion during seven seasons with the Cards.

But for Flood, the notion that a 12-year veteran could be bartered without his permission violated a basic personal right. Although he stood to make $100,000 with the Phillies (about $668,000 today), he decided to refuse the move and sit out the 1970 season.

Flood had been active in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and his letter to Bowie Kuhn, Major League Baseball commissioner, echoed that experience: “I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes.”

Kuhn—although sympathetic—refused, and Flood filed suit against the commissioner, the presidents of the two major leagues, and the 24 teams that existed at the time.

Flood received scant public support from other players. To many, baseball’s “reserve clause” allowing total team control of a player’s career seemed virtually inviolable. Baseball’s hold on the American imagination and its iron-fisted control of player contracts had allowed it to survive the 1919 Black Sox scandal, the Great Depression, segregation, franchise relocations and two major U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

In 1914, when challenged by a newly formed league, American and National League owners responded by buying off most of the emerging competition. When the owner of the Baltimore Terrapins won an $80,000 judgment under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, baseball found relief at the Supreme Court. In a perplexing 1922 opinion in Federal Baseball Club v. National League, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. ruled that baseball—where teams from various cities crossed state lines to play before paying audiences—couldn’t be considered a product of interstate commerce.

Likewise, when the Newark Bears, a New York Yankees farm club, disbanded in 1950, one of its promising pitchers refused reassignment to a lesser minor league squad. When George Earl Toolson demanded a chance to negotiate with other teams, he was met at the Supreme Court with a one-paragraph, 7-2 decision reiterating Federal Baseball.

Photograph of Curt Flood by AP Photo.

So in 1972, with the support of the Baseball Players Association, Flood was attempting to rekindle the antitrust issue before a historically skeptical high court. Although his lawyer, former Justice Arthur Goldberg, argued that the clause violated not only antitrust laws but 13th Amendment prohibitions against peonage and involuntary servitude, the response was all but assured.

On June 19, 1972, in an opinion that began with a nostalgic list of his favorite players, Justice Harry Blackmun reaffirmed his love of baseball and the court’s love of its antitrust exemption. But he expressed hope that the reserve-clause anomaly could be cured through labor negotiations.

That happened in 1975, when a federal arbitrator ruled that two players unilaterally signed by their teams to one-year contracts could become free agents. After a brief court challenge, team owners resolved the issue in a new labor contract with the players union, introducing free agency into the landscape of player compensation.

By then, Flood had retired from baseball. He bought a bar on the island of Mallorca in Spain, where he stayed until illness forced his return to the United States. He died in 1997. A year later, Congress enacted the Curt Flood Act of 1998, formally removing the reserve clause from baseball’s antitrust exemption.

Last year, after more than 40 years of free agency, 36 Major League players made $20 million or more.