Video cannot replace the courtroom sketch artist

In 1964, the Dallas courtroom where Jack Ruby stood trial for killing President John F. Kennedy’s alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. Jack Ruby (sitting), his defense attorneys Melvin Belli (standing) and Joe Tonahill (sitting). Judge Joe Brown presides. Illustration by Howard Brodie

Gary Myrick is an accomplished courtroom sketch artist—an artist-journalist, he calls himself—whose work has been seen by many TV news viewers. His work amazes, given the almost instant turnaround time, with richly textured, clear images. Long after cameras entered Texas courtrooms decades ago and stifled the business, he still calls this his vocation: “That’s what I am,” he says resolutely.

Myrick gets some trial work now and then, and two years ago, managed to quit working as a security guard in a half-full shopping center in a poor section of Fort Worth, Texas. That was the “real job” he had dreaded taking, doing so in the mid-1990s when his career was finally overwhelmed by the new video normal. He became eligible for Social Security retirement benefits in 2015. Before that, the Law Library of Congress, through a donor, purchased his archives. He has enough to get by.

“Business has been terrible for courtroom artists here in Texas,” says Myrick, who lives in Fort Worth. In his heyday in the 1980s he sketched three trials in three cities in one day for TV news.

“I used to do several trials a month, some of the big ones, gavel to gavel,” he says. Now it’s maybe a handful a year for a few days each.

Ticket into the courtroom

The art of courtroom sketching had a meteoric rise after TV news expanded from 15 minutes to a full half-hour in 1963. Months later, Howard Brodie, who had done combat sketches of U.S. troops in WWII, Korea and Vietnam, approached a friend at CBS News seeking assignment to illustrate the trial of Jack Ruby in the shooting death of Lee Harvey Oswald. Brodie got the work and the graphics-oriented television executives quickly recognized the art form as a way to take viewers where cameras couldn’t go.

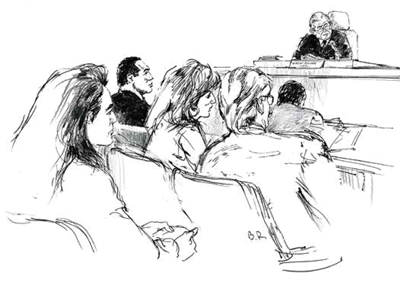

Judge Hiroshi Fujisaki on the bench during the 1996 wrongful death case against O.J. Simpson brought by the victims’ families. Nicole Brown Simpson’s sister Denise Brown (Left); the defendant (top left); Fred Goldman, father of Ron Goldman, sits next to his daughter, Kim. Illustration by Bill Robles.

But things changed after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1981 decision in Chandler v. Florida gave approval to cameras in the courtrooms. Now all 50 states have some variation on when, where and how cameras can be used.

Federal courts continue to resist the technology, thus still providing work for courtroom sketch artists.

“No, this is not a dying art,” says Bill Robles, who is based in Santa Monica, California, and succeeded Brodie as the unofficial dean of courtroom artists. “I’m just as busy and making more money than before. You don’t work every day unless you do a trial, and they come up once in a while.”

California is rich in high-profile trials, says Robles, whose comments belie the fact that he now is often the only illustrator at hearings. “A lot of judges were scared of cameras after the O.J. Simpson trial became such a circus,” he says, “and the ridicule Judge [Lance] Ito received.”

Robles drew this portrait of Simpson at the former football star’s civil trial. Illustration by Bill Robles.

Cameras had been banned from courtrooms after their abusive and distracting use in the 1935 trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann in the kidnapping death of Charles Lindbergh’s toddler son. As a result, the ABA approved Canon 35 of the Canons of Judicial Ethics to recommend against the use of cameras, and it was widely adopted.

Post-O.J., many California judges handling high-profile trials now invoke an option to ban cameras, Robles says.

Federal opportunities

The federal courts still keep Robles busy. Last June, he covered the Led Zeppelin copyright trial in U.S. district court in Los Angeles, where a jury found the band had not ripped off a riff from someone else’s music.

A force of his own in courthouses, when the trial ended, Robles was invited back into the courtroom by the head of security, where he got band members Robert Plant and Jimmy Page to autograph two of his drawings. That will bring in good money, in addition to his usual fee of $500 per day—$750 if a TV network’s affiliates also use his art.

After pleading no contest in May 1977 to charges related to spraying gunfire into a Sporting Goods Store in the Inglewood section of Los Angeles, Patty Hearst received probation. Illustration by Bill Robles.

Robles acknowledges that the business has been and is contracting.

“Sometimes I can go a month without getting something,” he says. “Also, the drawing pool has shrunk.”

Only two courtroom artists now typically get work in the Los Angeles region: Robles and Mona Shafer Edwards.

“Mona and Bill are about the best,” says Linda Deutsch, the Associated Press reporter who retired in 2014 after 48 years covering trials such as those of Charles Manson, Michael Jackson and Simpson.

“You almost feel like the subjects are there in front of you,” she says of their art. “They work so quickly, and it’s just incredible how in a couple of minutes they can grab an expression or movement.”

Deutsch and Robles met in 1970 at the Manson trial. It was the first trial for the reporter and the artist, and the launchpad for their fame.

in February 1976, Hearst took the witness stand during her trial in San Francisco for her role in a bank holdup committed with the Symbionese Liberation Army. Illustration by Bill Robles.

Robles’ sketch of Manson leaping from his seat in an attempt to assault the judge displays a tantalizingly kinetic detail of motion, including a pencil falling from the defendant’s grasp as he flew through the air. It led the CBS News broadcast that evening.

The Manson drawing is also the cover for the book The Illustrated Courtroom: 50 Years of Court Art by courtroom illustrator Elizabeth Williams and crime writer Sue Russell. Featuring drawings from high-profile trials between 1964 and 2014, it includes work by Brodie, Robles, Williams, Aggie Kenny and Richard Tomlinson.

“There was this great boom of wonderful courtroom art beginning with Howard Brodie’s first trial, and it lasted into the 2000s,” says Williams, who spent nine years on the book. “There’s never going to be another time like this, and there wasn’t before.”

FISCAL RESTRAINTS

The problem isn’t just cameras in courtrooms, Williams says: “The news budgets were bigger. They keep cutting, and that includes us.”

The Library of Congress began acquiring courtroom sketches in 1965 and now has more than 10,000, including Brodie’s work from the Ruby trial. Last year, the library purchased a collection of 95 original drawings from high-profile trials over four decades, with work by Kenny, Robles and Williams.

The purchase was funded by Thomas V. Girardi, founding partner of the Los Angeles law firm Girardi Keese, who is on the library’s private-sector advisory board. Girardi was lead counsel in litigation against Pacific Gas & Electric Co., the basis for the film Erin Brockovich.

Roman Polanski on the witness stand in 1977. Illustration by Bill Robles.

The new addition includes some gems that never saw the light of TV or print. They include Kenny’s drawing of an obscure witness sporting a bright-red tie during the 1974 trial of U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell and Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans, both charged with and acquitted of blocking an investigation of secret funding for the Watergate burglary. The witness: FBI’s No. 2 official W. Mark Felt, who in 2005 admitted that he was Deep Throat, the source for the Washington Post’s exposé.

The library also got funding for an exhibit of courtroom art called “Drawing Justice,” says Sara W. Duke, a curator for popular and applied graphic art. It features 98 illustrations, from 1964 to the present day. It will be open until Oct. 28 in the library’s South Gallery in the Thomas Jefferson Building in Washington, D.C.

the art of the trial

Williams got her start in 1980, thanks to a helping hand from Robles, who looked at some of her drawings and introduced her to a reporter for a TV station that didn’t have an artist. She soon was working trials regularly in the greater LA area.

Her stint there was capped by the pretrial hearings and trial of auto executive John DeLorean. DeLorean was charged in October 1982 with bankrolling a huge cocaine deal; a jury found him not guilty two years later.

At the trial, Williams did an unusual sketch that didn’t make it onto TV news. During a break, she was permitted to sit where the lawyers do in court, and she looked back at her colleagues finishing sketches they’d outlined during the hearing. She drew them at work and inserted herself in her usual place. They are Brodie, Bill Lignante, Robles, David Rose, Walt Stewart and Williams.

On June 13, 2005, Michael Jackson sat motionless when the verdict of not guilty was read for each count in a child molestation trial, which triggered tears of relief from the entertainer. Illustration by Bill Robles.

After the DeLorean trial, Williams left for New York City because as well as courtroom sketching, she wanted to do general illustration work such as advertising and fashion.

“In LA, that’s more focused on Hollywood, and I didn’t want to get into it,” Williams says. “And it was easy to get courtroom work in New York because my [TV] clients in LA provided introductions.”

She still gets trial assignments somewhat regularly but augments her income with other work, including New Jersey State Bar Association events: Lawyers seem to like courtroom-art style illustrations of their meetings.

This year, the New Jersey Bar Foundation expanded its educational programs for public understanding of the law by adding something to the mock trial competition for high school students: the Courtroom Artist Student Competition, in which student artists sketched their school’s mock trial team at work in local courthouses.

This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with the headline "Drawn To It: Video displaces—but can't replace—the courtroom sketch artist."