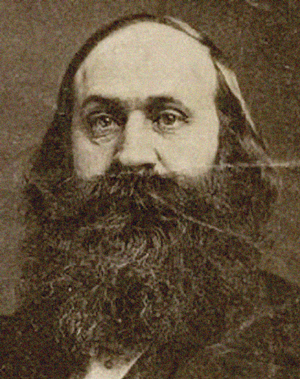

March 7, 1859: Court confirms abolitionist's conviction

Sherman Booth.

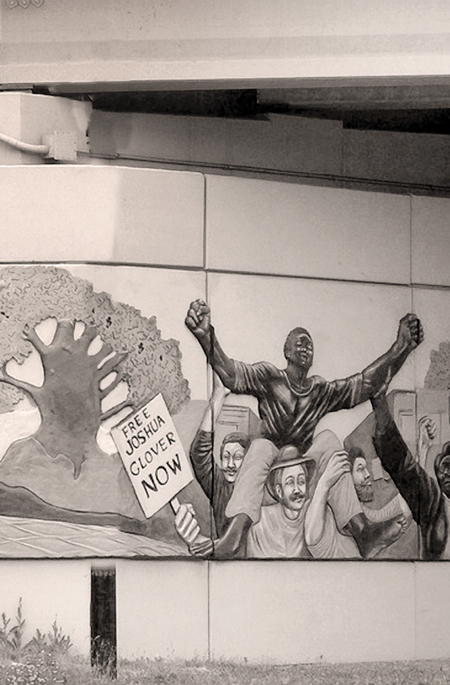

A group of men—including several U.S. marshals—burst upon a card game at a cabin in Racine, Wisconsin, in March of 1854. Led by Missouri farmer B.S. Garland, the posse aimed to capture one of the cardplayers, Joshua Glover, who was a runaway slave. He resisted but was quickly overpowered. Beaten and manacled, Glover was loaded into a wagon and carted away to Milwaukee, where he was jailed while awaiting transport back to the farm outside St. Louis he’d escaped from two years earlier.

In Wisconsin, Glover enjoyed a job in a sawmill and the support of a fiercely abolitionist culture, which included Sherman Booth, editor of the Wisconsin Free Democrat and soon to become a founder of the Republican Party. Hearing that an escaped slave was being held in Milwaukee, Booth recruited a mob of abolitionist sympathizers who stormed the prison, freed Glover and placed him in hiding. Glover would later be transported to Canada, but for Booth the legal implications were only beginning.

Milwaukee artist Ammar Nsoroma’s mural on the Fond du Lac Avenue freeway underpass tells the story of runaway slave Joshua Glover. Photographs Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Flickr.

Some of the most divisive constitutional battles in U.S. history have emerged from the vague wording of Article IV, Section 2, Paragraph 3, the “fugitive slave clause.” The ambiguity was intentional, a compromise among the founders. In its final form, it required nonslave states to return captured runaways to their owners; but it avoided wording that would recognize slavery as either a moral institution or a constitutional fact.

Northern states viewed slavery as state-specific and responded in kind. When Congress codified the fugitive clause in 1793, anti-slavery states responded with “personal liberty laws” that required formal court proceedings before any slave repatriation. But as part of the Compromise of 1850, Congress tightened provisions for returning fugitive slaves.

The new law provided cash incentives for law enforcement to hunt and capture runaways and stiff fines for those who refused to do so. Private citizens who aided fugitives could be imprisoned. Moreover, slave owners were obliged to offer little proof to support a claim, and fugitives were stripped of any right to demand proof. Northerners were outraged—and none more deeply than Wisconsin abolitionists.

While under arrest, Glover had been in the custody of U.S. Marshal Stephen Ableman, who had Booth arrested for his part in the escape, citing the 1850 legislation. Wisconsin courts were hostile to the charges and released Booth from federal custody on a state writ of habeas corpus. After Ableman appealed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, it declared the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 unconstitutional, a violation of state sovereignty. When the dispute reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1859, Glover was already in Canada, and Wisconsin courts simply ignored federal rulings on the matter. But the nation had continued pulling itself apart over the conflicts presented by Ableman v. Booth: federal primacy, state sovereignty and the ever-present issue of slavery.

In a unanimous decision released on March 7, 1859, Chief Justice Roger Taney declared that state courts have no right to interfere with or ignore the federal process. The Constitution’s supremacy clause, the court ruled, means what it says: Where there is conflict, federal authority prevails over state sovereignty.

Booth’s conviction held, but resistance on his behalf continued with several attempts to force his release and one successful escape. But Booth was too old, too notorious and too committed to abolition to stay away from the public fray. To make matters worse, he was indicted in 1860 and tried on a charge of seducing a 14-year-old girl. The jury deadlocked, but his credibility on moral issues was destroyed.

The legacy of Ableman v. Booth proved enduring and, ultimately, ironic. Where the Taney court’s opinion had been used to secure federal help in the preservation of slave ownership, that same primacy of federal authority proved to be a vital weapon in the 20th-century effort to secure and protect civil rights.