March 27, 1876: Colfax massacre convictions tossed

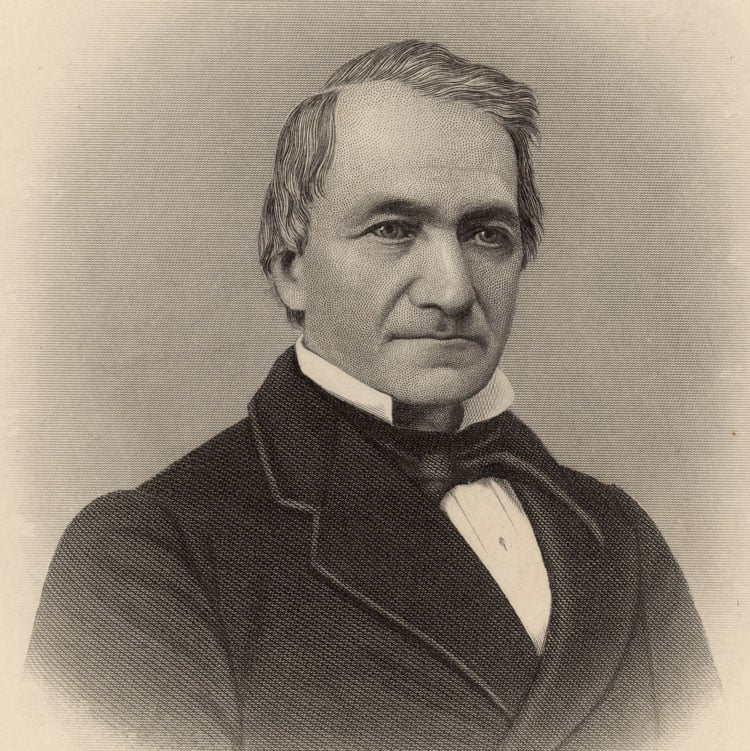

Justice Joseph P. Bradley. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

On Easter Sunday in 1873, a heavily armed group of white men led by Christopher Columbus Nash laid siege to the Grant Parish courthouse in the Louisiana town of Colfax. The aim of the assault by 300 white Democrats, many of them former Confederate soldiers, was to dislodge an armed cadre of 150 freedmen and white Republicans who had barricaded themselves inside to protect what they believed was the integrity of their local election.

At the time, Louisiana was one of three formerly Confederate states where Black citizens outnumbered white citizens. But eight years after the murder of Abraham Lincoln and the end of the Civil War, Southern whites, and more than a few of their Northern supporters, were bristling—often with violence—against freed slaves, their Republican supporters and the so-called Reconstruction amendments to the U.S. Constitution designed to create a more universal American citizenship.

For local whites, changes wrought by Reconstruction were plentiful. Grant Parish, for instance, had been formed from two surrounding parishes and renamed for the nation’s 18th president. Calhoun’s Landing, once named for plantation owner Meredith Calhoun, was renamed for Grant’s vice president, Schuyler Colfax.

Nearly everywhere in the South, elections were particularly caustic. And in Louisiana, the election of 1872 was especially painful. With the election plagued by factionalism, racism, voter suppression and charges of fraud from both sides, Republicans and Democrats formed parallel administrations: Republicans sought protection from the federal government; the Democrats relied on racist paramilitary groups. And when the Republican governor certified the Republican candidates as judge and sheriff in Grant Parish, Black former soldiers flocked to Colfax to protect them.

Nash, who had been the Democrats’ candidate for sheriff, responded in kind with a paramilitary force that spent 13 days assaulting the courthouse with horse soldiers and light artillery. When they finally set the building ablaze, the Republicans abandoned their positions. Once outside, many were slaughtered by men on horseback. According to witnesses, at least 37 were taken prisoner and killed that night by gunshots to the back of the head.

News of the Colfax massacre reached James Beckwith, a federal prosecutor in New Orleans. Backed by the Enforcement Act of 1870 and federal soldiers who had arrived at the scene, Beckwith headed to Colfax to investigate; soon after, 97 marauders had been identified and indicted under the federal law.

Convictions under the Enforcement Act weren’t as rare as might be imagined—there had been at least 800 in North Carolina, South Carolina and Mississippi. But in Grant Parish, so many defendants had scattered and so many witnesses intimidated that only nine defendants were actually tried in New Orleans. Of those, only three—among them William Cruikshank—were convicted by a mostly white jury on 16 of 32 federal counts of conspiracy.

Under the Judiciary Act of 1869, the U.S. Supreme Court had been expanded from seven to nine justices and the nation divided into nine circuits. To each circuit was assigned a residing circuit judge and one of the nine Supreme Court justices. So when Cruikshank’s case was appealed, it landed before William Woods, the presiding circuit judge, and Joseph P. Bradley, one of the new justices appointed to the expanded Supreme Court.

Although Woods upheld the convictions, Bradley overturned them in an extraordinarily bold decision. Bradley reasoned that the Enforcement Act was intended to curtail the states from denying the franchise to Black voters, and that the federal law held no power over individual citizens such as Cruikshank and his paramilitary comrades. Where the 13th and 14th Amendments granted freedom and citizenship to former slaves, they granted no constitutional rights not already protected by state laws.

By the time the full court decided U.S. v. Cruikshank on March 27, 1876, Bradley’s reasoning had been fully embraced by his colleagues. But Bradley’s decision to overturn the Colfax massacre convictions already had been embraced by terrorist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camelia as a license to use violence to regain white rule in the South,“thanks to Justice Bradley.”