The University of Idaho case last year in which four students were slain inside an off-campus home sent shockwaves through the college community and the country—and the crime sent the media into overdrive.

The tragedy, which occurred in Moscow, Idaho, on Nov. 13, sparked a coordinated investigation among the Moscow Police Department, the Idaho State Police and the FBI. More than 113 pieces of physical evidence were gathered, and 19,650 tips were submitted by the public via email, phone calls and digital media. Idaho Gov. Brad Little directed that up to $1 million in state emergency funds be used to solve the mystery of who was responsible for the stabbing deaths of Ethan Chapin, 20; Madison Mogen, 21; Xana Kernodle, 20; and Kaylee Goncalves, 21.

In addition to law enforcement looking for the killer, an army of true-crime internet sleuths also scrutinized the case. Bearing laptops and cellphones and brimming with theories, the gregarious crime-solvers converged on multiple social media platforms, fixated on events as they unfolded. Users went so far as to identify by name people they felt were suspects—or should be—without presenting any facts. One private Facebook group—the University of Idaho Murders Case Discussion—attracted nearly 225,000 members.

On Dec. 30, authorities arrested Bryan Kohberger, a PhD criminology student at Washington State University in connection with the case; he was charged with four counts of first-degree murder in addition to one count of burglary. A preliminary hearing has been set for June 26.

But one University of Idaho professor is still dealing with the aftermath of an online sleuth’s accusations against her. Texas-based TikTok personality Ashley Guillard—who neither attended the university nor knew the victims—produced a series of videos, some of which have been viewed more than 1 million times, accusing associate professor and history department chair Rebecca Scofield of orchestrating the murders.

Through her attorneys, Scofield sent Guillard two cease-and-desist letters. Scofield—who says in her lawsuit she was traveling outside of Idaho with her husband when the murders occurred—did not know any of the victims and was never identified as a suspect by police. After Guillard’s videos remained online, Scofield sued in the U.S. District Court for the District of Idaho on Dec. 21, alleging she was defamed by “Guillard’s false TikToks.”

“Defendant Ashley Guillard—a purported internet sleuth—decided to use the community’s pain for her online self-promotion,” according to the complaint. “She has posted many videos on TikTok falsely stating that plaintiff Rebecca Scofield … participated in the murders because she was romantically involved with one of the victims.”

The evolution of the internet and social media has handed more people a soapbox on which to share opinions and information. As of January 2023, there were 5.16 billion internet users, and 4.76 billion of them use social media, according to Statista, which provides market and consumer data.

With the popularity of social media platforms like Facebook, TikTok, Reddit, Twitter and YouTube, online armchair detectives have been able to help authorities in some cases by offering tips. But there also have been instances of misinformation, fake experts and unsupported theories being presented as fact and of innocent people being targeted.

As Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 exists today, the individuals are solely liable for content they post—the platform is not.

Users of social media indirectly benefit because the platforms allow them to engage in a broad range of unmoderated speech and have limitless reach. But some experts say the threat of criminal charges or a lawsuit may not be enough to slow down bad actors. Others contend amending the law could encourage overzealous moderation on the part of platforms to avoid lawsuits.

"Since there are no regulations on social media, it's the Wild West." - Chris McDonough

In 24 states, as tracked by the American Civil Liberties Union, users who post defaming statements or pictures can incur criminal charges for damaging another person’s reputation. In Idaho, those charges can result in up to six months of prison time or fines not exceeding $5,000.

The law protects social media platforms from certain types of civil actions relating to the content posted by the platforms’ users. Still, there have been several challenges to amend the statute. In 2020, the Department of Justice under President Donald Trump’s administration issued recommendations for reforming the law, submitted to Congress by then-Attorney General William Barr.

In addition, several bills have been introduced in Congress. In February, the Internet Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency Act was reintroduced by Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, and Sen. John Thune, R-S.D. The bipartisan legislation requires social media companies to establish clear content moderation policies and hold them accountable for content that violates their own policies or is illegal.

The Safeguarding Against Fraud, Exploitation, Threats, Extremism and Consumer Harms Act, known as SAFE TECH, also was reintroduced in February and proposes several changes to the law, among them that social media companies be held accountable for enabling online harassment and stalking and “address misuse on their platforms or face civil liability,” according to a press release.

Until the law is changed, the world of true-crime sleuthing will continue to offer information, accurate or not, that gets shared again and again.

Social media “gives everyone a platform and a megaphone,” says Kermit Roosevelt III, the David Berger Professor for the Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and author of The Nation That Never Was: Reconstructing America’s Story.

“Most of the time, if you’ve got the internet sleuth who says, ‘Often in these cases, it’s the boyfriend. I think they should look at the boyfriend,’ that’s totally fine,” Roosevelt says. “No harm done to anyone there because it’s true. A good investigation would look at the boyfriend. It’s when you get the baseless accusations of guilt and the fabrication of all these other things that suggests that someone is not actually looking at the evidence and thinking reasonably about what it suggests, that’s a problem. It certainly is something that social media has facilitated.”

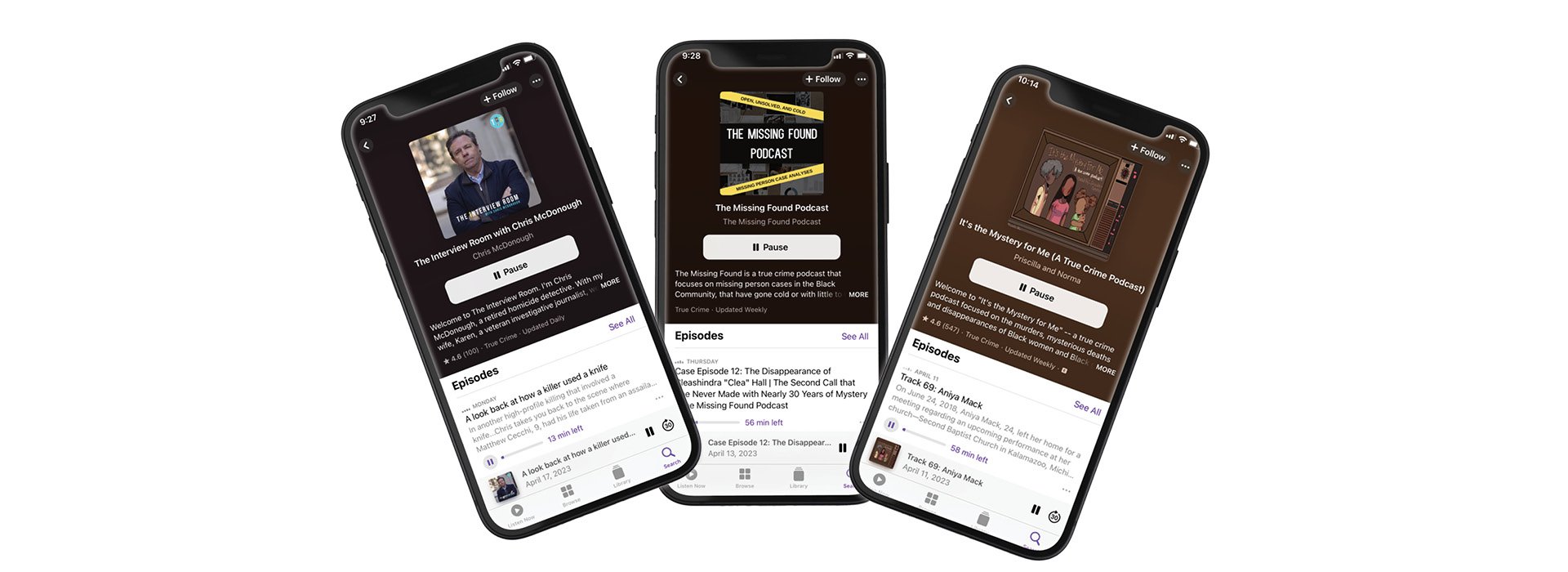

Chris McDonough, a retired homicide detective and host of the YouTube podcast The Interview Room, has worked more than 300 homicide cases during his career.

“Since there are no regulations on social media, it’s the Wild West,” says McDonough, who is also a director with the Cold Case Foundation, where he actively works alongside law enforcement and victims’ families, using social media as a platform to bring awareness to cases in hopes of solving them.

“Most people don’t realize it’s like a theatrical stage,” McDonough says. “Anyone can get on there and purport themselves to be an expert when they’re not. When nonexperts wildly speculate about true-crime cases and publicly broadcast rumors and speculation, it can end up damaging reputations. The Idaho college murders is an example of that.”

According to Section 230, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

The law also provides protection for companies to take down content it deems “objectionable” based on several listed criteria, if the content is “voluntarily taken in good faith.” The provider has this right “whether or not such material is constitutionally protected,” the law says.

Section 230 was signed into law 27 years ago, before Twitter, Facebook and TikTok became embedded into everyday culture and the lexicon, and only about 40 million people worldwide were using the internet, according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which calls it “one of the most important laws protecting free speech online.”

Roosevelt says defamation is so much easier now because of social media.

“It may be a defamation lawsuit against the speaker isn’t an adequate remedy because there are people who won’t be deterred by the threat of liability, either because they are legally unsophisticated, or they just have very poor judgment, or they don’t have a lot of assets. So people might engage in this behavior, despite the fact that it generates a strong case against them,” he adds. “That’s a problem. There might not be adequate resources to satisfy a judgment, so you can’t really get compensation if you’ve been defamed.”

"Courts and juries are demonstrating through their decisions and verdicts that they understand how devastating and damaging online defamation and misinformation can be.” - Michael Pelagalli

Michael Pelagalli, a Cleveland attorney specializing in internet defamation with the firm Minc Law, says, “States are very limited in how they can criminalize speech-related activities.”

“I don’t believe more states will look to bring back previously repealed criminal statutes, especially because many were deemed unconstitutional” based on free speech, Pelagalli says. “However, defamation remains a viable civil claim across the country, and courts and juries are demonstrating through their decisions and verdicts that they understand how devastating and damaging online defamation and misinformation can be.”

Pelagalli says too much of an overhaul of the law would destroy the internet for those who use and enjoy it responsibly.

“It is becoming clear that market and political forces are starting to effectuate change within these platforms to address these modern-day issues,” Pelagalli says. “Where Section 230 could be improved, without running the risk of completely overhauling the modern-day internet, is by compelling the social media platforms and other ‘interactive computer services’ to take action to remove content once it has been deemed defamatory or unlawful by a court of law.”

One of two cases concerning Section 230 currently before the U.S. Supreme Court is Gonzalez v. Google, involving 23-year-old Nohemi Gonzalez, an American student who was killed in a 2015 Islamic State group attack in Paris. Gonzalez’s family is suing Google (which also owns YouTube), Facebook and Twitter. The case alleges Google aided and abetted international terrorism with video recommendations that helped the Islamic State group recruit members via YouTube, in violation of the Anti-Terrorism Act. The court had not ruled in the case at press time. [Editor’s note: On May 18, the Supreme Court ruled in Twitter v. Taamneh that tech companies were not liable for allowing the Islamic State group to use their platforms in their terrorism efforts. Companion case Google v. Gonzalez was vacated and remanded to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.]

Mukund Rathi, an attorney and Stanton Legal Fellow at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, is listed as counsel on the amicus brief from the foundation and other entities supporting Google in the case. According to Rathi, Section 230 provides additional protections on top of the First Amendment, which protects all kinds of media.

“Social media platforms, just like any publisher, do have the right to publish content, not publish content, recommend content,” he says. “To me, that’s the exact same decision that the New York Times makes when it decides what’s above the fold and what’s below the fold. That’s the publisher’s decision. And that is the type of thing that the First Amendment protects.”

Galvanizing online users has been the trademark of social media platforms, especially in movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter. These platforms also played a role in another high-profile uprising: the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The insurrection unified online sleuths who crowdsourced information. A group known as the “Deep State Dogs”—its Twitter home page reads: “If you attacked a law enforcement officer, the press or vandalized property at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, we’re coming after you”—delved into a video of Metropolitan Police Officer Michael Fanone being attacked with a Taser.

The group identified a possible suspect in the officer’s attack as Daniel Rodriguez and shared its findings with the police. Rodriguez, a California resident, was later charged with eight federal counts, including conspiracy and inflicting bodily injury on an officer using a dangerous weapon; he pleaded guilty to four counts.

In a less successful mission, many internet sleuths may have attempted to locate the whereabouts of “Via Getty,” a man at the Capitol who was captured in a photograph smiling, waving and cradling a podium. The photo went viral, and many assumed his name was Via Getty—which was, in fact, an actual reference to the media company that supplies images.

Online sleuths were credited with helping the FBI identify many Capitol rioters. Still, in the Idaho case, before a suspect was apprehended, police monitored the internet’s true-crime community’s involvement in spreading misinformation and threatened criminal charges.

According to McDonough, the role of true-crime podcasters is not to solve cases but to facilitate discussion about known facts released by public officials.

“Opinion from an expert is one thing, but speculation from nonexperts can lead down a slippery slope,” he says.

As online sleuths and podcasters become more integrated in the crime-solving space, there has been a renewed interest in how media coverage and police investigations are reported and conducted.

In 2022, Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., who was chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform’s Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, held a hearing to investigate the unequal rates at which Black, Indigenous and people of color go missing and how those cases are handled by media and law enforcement.

According to the Committee on Oversight and Accountability, in 2020, 40% of all women and girls reported missing were people of color, or 100,000 out of 250,000, while they make up just 16% of the population. According to the committee’s report, in that same year, Black women and girls made up 13% of the female population in the country but accounted for 35% of all missing women.

The crisis extends to Native American women and girls. An August 2022 American University Magazine article, “3 Minutes on Missing White Woman Syndrome,” noted that the state of Wyoming—where Instagram travel blogger Gabby Petito, a white woman, was reported missing in September 2021—is home to more than 400 Indigenous women and girls who disappeared between 2011 and 2020.

“Missing White Woman Syndrome,” a term popularized in 2004 by journalist Gwen Ifill, raises issues of fairness and accuracy in reporting how women are covered in the media depending on their race and level of attractiveness. Some true-crime podcasters see the problem as ongoing in the online space.

Enter sisters Norma and Priscilla Hamilton, self-described “fabulous Black & Afro-Latina Queens” who host It’s the Mystery for Me, a weekly true-crime podcast focusing on both solved and unsolved cases in the Black community. Priscilla, who is a corporate attorney in New York City, and Norma, a 2022 graduate of Touro University Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, both inherited a love of true-crime shows from their mother.

“As we got older, we started watching for ourselves,” Norma Hamilton says. “There was a narrative that was being told that was not including Black women and Black girls specifically, and we felt like we had to fill that void in some way.”

Their law background reminds them of the legal consequences that can arise from podcasts that do not make content accuracy a priority, and the two practice fastidious fact-checking, often editing out anything potentially problematic. The sisters also follow how online defamation cases are handled by the courts.

For Jadyn Harlow, a West Coast sleuth and the host of The Missing Found podcast, ensuring names of missing Black women garner some attention is her main objective. Harlow says she doesn’t post as frequently as some podcasters because she can sometimes spend as many as 50 hours on one podcast: scouring websites, collecting maps, editing, finding photos, writing and uploading video to social media platforms.

Harlow recalls the unsolved case of 8-year-old Relisha Rudd, who went missing on March 1, 2014, in Washington, D.C. The case still haunts her. A picture of the bright-eyed girl with her hair in braids appears on a missing persons poster online. Rudd disappeared while living in a homeless shelter with family members. Harlow recalls the case getting some media attention.

“And things just died down,” she says. “That’s why I put these cases out, so that they can get back into the media rotation. … I don’t want people to forget that these people are missing. Yes, there are other people missing. But when it comes to African Americans missing, we don’t get enough coverage at all.”

In November, the Columbia Journalism Review collaborated with ad agency TBWA/Chiat/Day/New York to examine how race determines the level of media coverage. Of the 3,600 articles on missing people between January and November 2021, there was a disparity in how people of different racial and ethnic groups were covered in media. According to the study’s findings, a young white adult woman who went missing in New York would be covered in 67 news stories; a young Latino adult male may only appear in 17. A middle-aged Black man reported missing would receive four or fewer mentions of his disappearance in the media.

“I say all the time that we also have JonBenét Ramseys in our community and Chandra Levys and Natalee Holloways—just everyone that people hyperfixate on,” Priscilla Hamilton says. “I really hope people see it and start to show this on TV more. If anything, for educational purposes and to alert the public that this is not just happening to one group of people; this is happening to everybody.”

Investigations in which social media sleuths have helped law enforcement solve crimes cannot be dismissed, such as in the Jan. 6 insurrection and the Petito case, which caught a break when someone online spotted the victim’s van. Users of online platforms, including sleuths, have benefited from legal immunity. Whether proposed changes to the law by Congress or the courts will change things remains to be seen.

“One of the reasons that organizations like [the Electronic Frontier Foundation] supports that immunity is because we think it ultimately serves ordinary internet users,” Rathi says. “The ones who are trying to post their content online and the ones who are trying to find interesting content.”