Chang Wang walks the line to teach constitutional law in Beijing

Chang Wang: “There are only two things that can bring me close to tears: Chinese literature and American law.”

Chang Wang was an art student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign when a PBS miniseries changed the trajectory of his life.

When Wang arrived in the United States in 2000 to study for a master’s degree in art history, he already had earned a bachelor’s degree in filmmaking from the Beijing Film Academy and a master’s in comparative literature and comparative cultural studies from Peking University.

He liked to visit the University of Illinois’ library to watch films and documentaries. It was there that he stumbled upon the 1987 documentary series Eyes on the Prize, a history of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ’60s.

“I can’t remember how many times I cried,” Wang says. “It was a life-changing learning experience. I studied a lot of theory in art school, but nothing struck me to the heart like learning about the civil rights movement.”

For Wang, who was born in Beijing in 1972 with Chairman Mao Zedong ruling the People’s Republic of China, hearing about the power that people had to effect change was staggering. When he learned that in the United States a citizen could challenge the government in court and prevail, he was driven to find out more.

He went to the library to listen to recordings of oral arguments in U.S. Supreme Court cases. He read Clarence Darrow’s autobiography. He watched archival footage of the Army-McCarthy hearings and was struck by the exchange between the Army’s chief counsel, Joseph Welch, and the powerful Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Wang says he was thrilled by the audaciousness of Welch asking McCarthy: “Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?”

And so, after 10 full years of study devoted to the arts, Wang decided he was changing course. After he completed his degree at the U of I, he enrolled at the University of Minnesota Law School.

In the 11 years since Wang earned his law degree, he has become an advocate for democracy and the rule of law, a cross-cultural ambassador and a prolific writer. He lives in St. Paul with his wife and three dogs and is the chief research and academic officer at Thomson Reuters, where he has worked since graduating.

Photo courtesy of Thomson Reuters

LEADING BY EXAMPLE

Wang has been an ABA member since 2011 and has participated in many ABA committees on topics such as immigration and naturalization, international law, and arts and cultural heritage law. He has adjunct faculty and guest lecturer status at several institutions and works to fire up students with the same love for constitutional law he discovered in himself.

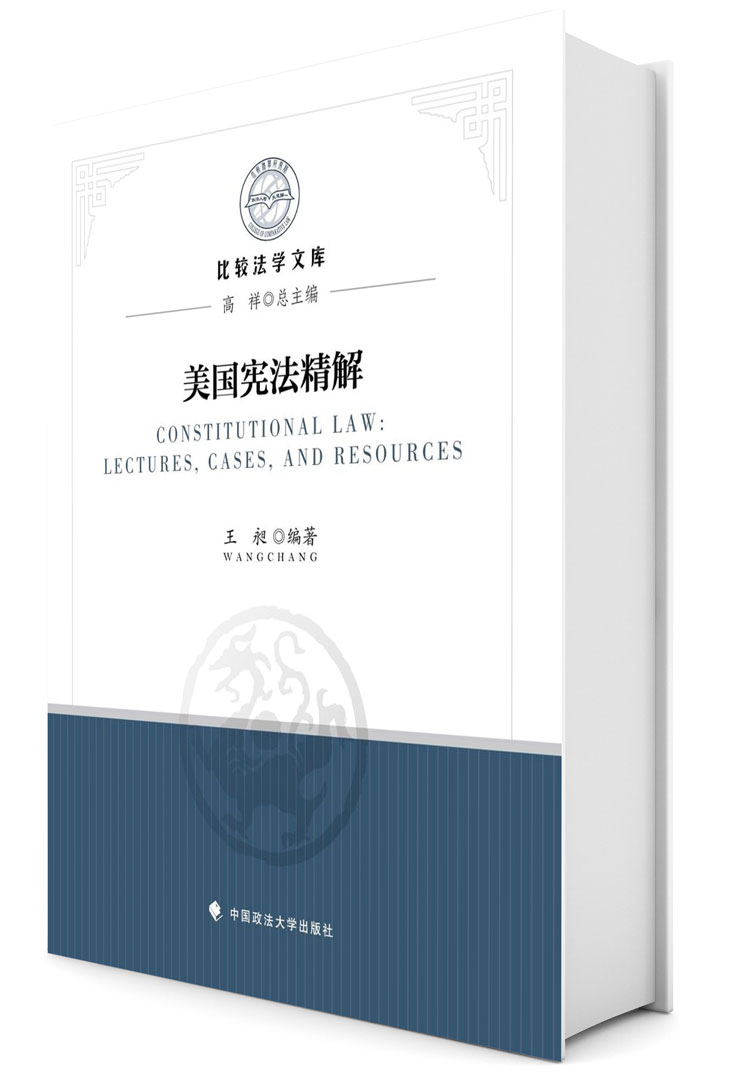

In the spring, Wang usually travels back to Beijing to teach students at the China University of Political Science and Law about American constitutional law. This year, he brought with him a textbook he had written and edited with more than a dozen research assistants. That team translated into Mandarin the U.S. Constitution, the state constitutions of Minnesota and Massachusetts, the Magna Carta and the headnotes on 39 seminal Supreme Court cases. Constitutional Law: Lectures, Cases, and Resources includes 25 lectures written by Wang, is 1,200 pages long and comes in two volumes.

Thomson Reuters reports that it is the first English-to-Chinese textbook on U.S. constitutional law.

“We have positive reactions from all the major law schools in Beijing and Shanghai, and at least 15 of them have adopted the textbook as the official textbook or reference book for their comparative law teaching,” Wang says. “As a textbook, we do not expect it to be a best-seller. The publisher printed 5,000 copies for the first run, and it’s doing pretty well. The publisher is very happy, given the fact that I do not receive any royalties, for this is a collaborative research project by Thomson Reuters and China University of Political Science and Law.”

The World Economic Forum reports that China is producing twice as many graduates from higher-education institutions as the United States, and that law is the fastest-growing area of study. Wang, who once served as vice-chair of the ABA Committee on International Legal Education and Specialist Certification, has found eager audiences when he teaches American law abroad.

“What’s happening in the United States is fascinating to foreign students,” Wang says. While he’d planned to cover familiar historical cases such as Marbury v. Madison and more recent cases such as Obergefell v. Hodges for his Beijing students this past spring, he found that his students were captivated by the travel ban litigation and emoluments clause lawsuits against President Donald Trump’s administration.

The travel ban cases in particular seemed to be unbelievable to people used to the Chinese legal system, which is still controlled by the Communist Party.

“In the United States, rule of law means that nobody is above the law. But in China it means ‘I will rule you by law,’ ” Wang says. In legal systems based on the Magna Carta, “even the king is subject to the rule of law. But that concept does not exist in the Chinese system.”

For Wang’s law students, the idea that a little-known judge in Hawaii had the power to stop the president’s administration from implementing a travel ban was stunning.

“The students were mesmerized and very surprised to see how constitutional law can be used in real life to protect institutions, to protect citizens’ rights and to protect constitutional democracy,” Wang says. “And, of course, when we get to the Bill of Rights, they’re also very surprised to see the Bill of Rights is alive. The Constitution of the United States is a living document. It keeps evolving; it’s not something we just regard as a canon and just put on the bookshelf.”

The political climate in China can make discussing civil rights and the American system of law a tricky venture. Government minders attend Wang’s lectures, in which he deliberately focuses on explaining how the law works in the United States without directly contrasting it to the Chinese system, where judges are appointed by the Communist Party and subject to its control.

Wang knew some of the human rights attorneys who were swept up by the Chinese government in a July 2015 crackdown. He is careful about what he says and does in China.

“I do not hide my opinion. But I think I know where the line is, and I do not want to cross the line,” he says. “Of course, the human rights lawyers thought they knew where the line was, too. But the authorities keep moving the line.”

As an example of how this can impact his work, when Wang was doing the final edits on his book, he adjusted his dedication.

“It was ‘to Chinese civil rights lawyers’ on the manuscript but only ‘to Chinese lawyers’ on the dedication page of the printed book,” Wang says. “I believe this is one of the lines that cannot be crossed.”

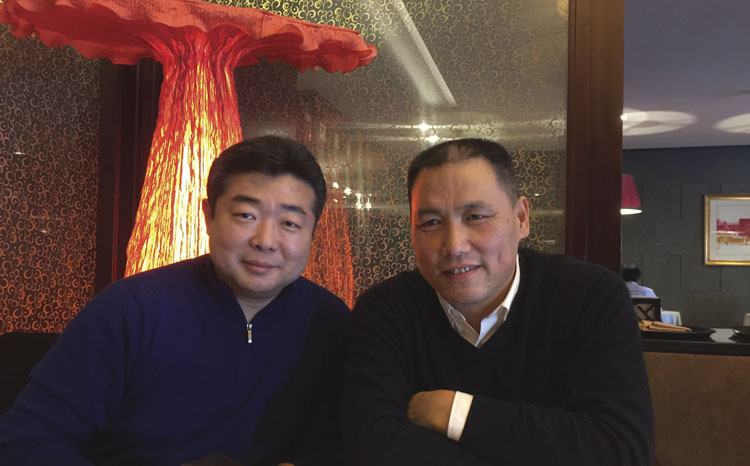

Wang with civil rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang. Photo courtesy of Thomson Reuters.

This article appeared in the December 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Law in Translation: Chang Wang walks the line to teach constitutional law to students in Beijing."

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.