Candy and snack companies sued for packages with empty space instead of extra product

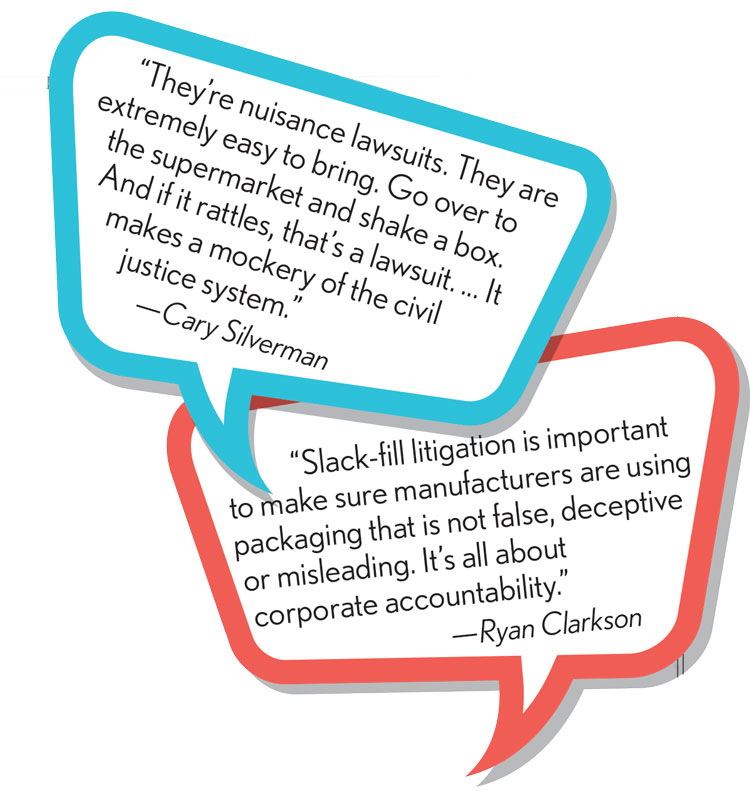

Cary Silverman: “They’re nuisance lawsuits. They are extremely easy to bring. Go over to the supermarket and shake a box. And if it rattles, that’s a lawsuit. ... It makes a mockery of the civil justice system.” Ryan Clarkson: “Slack-fill litigation is important to make sure manufacturers are using packaging that is not false, deceptive or misleading. It’s all about corporate accountability.” Illustration by Mhatzapa/Shutterstock.com

Lee has successfully defended New Jersey-based food conglomerate Mondelez International Inc. against three slack-fill lawsuits that complained about the packaging of Sour Patch candies, Swedish Fish and Go-Paks of Mini Oreos and other cookies. Lee says he often asks judges to use common sense. “What we pointed out a lot of times is that if you just pick up the box of food or candy ... you can feel the product shifting and moving,” he says. “So you know it’s not filled to the absolute brim.”

U.S. District Judge Sara L. Ellis seemed sarcastic in a Feb. 28 ruling in Chicago, when she tossed a lawsuit against Fannie May Confections Brands. She noted that plaintiffs Clarisha Benson and Lorenzo Smith “were saddened to discover upon opening their boxes of Mint Meltaways and Pixies that the boxes were not brimming with delectable goodies.” The judge dismissed these “barebones allegations.”

And she also set up a sort of Catch-22 for shoppers who want to sue: After you’ve purchased one package and discovered that its contents are more meager than expected, that serves as your warning about future purchases. “Already aware of Fannie May’s alleged deceptive practices, plaintiffs cannot claim they will be deceived again in the future,” Ellis wrote.

In Jefferson City, Missouri, U.S. District Judge Nanette K. Laughrey made the same point when she granted a summary judgment for the Hershey Co. on Feb. 16. Robert Bratton was suing the chocolate-maker, complaining about the space in Reese’s Pieces and Whoppers packages. But Bratton testified that he’d bought these candies hundreds of times over a decade—even though he knew the boxes were 30 to 40 percent empty. “I had a good idea that that’s what I was going to get, yes, ma’am,” he said, pointing out that he didn’t have much choice when he was at a movie theater with his children. “I needed to buy the candy and ... Whoppers and Reese’s is what I generally get for the kids. ... I can’t take outside food into the theater. So I’m kind of stuck with what they have.” This testimony led the judge to conclude that Bratton “cannot demonstrate that he was injured by any purportedly deceptive practice by Hershey.”

Juicy incentives

Such rulings may discourage slack-fill lawsuits, but settlements like Ferrara Candy’s agreement in the Jujyfruits case may offer an incentive for litigants. When that settlement comes up for final approval on Oct. 25, Clarkson’s firm will seek $750,000 in fees, plus costs and expenses, while asking for Iglesias to get $5,000. Silverman, the lawyer who co-wrote the U.S. Chamber report, criticizes these fees as exorbitant, pointing to them as an example of how money motivates frivolous lawsuits. But Clarkson says it’s fair payment for his firm’s work, including the hiring of experts. “If we lose at any stage, we run the risk of getting paid nothing,” he says.

David Greenstein of Los Angeles says he’s filed roughly 75 slack-fill cases over the years. “I’m almost 80 years old, and I remember growing up when you could trust what was in a box,” he says.

A former lawyer who was disbarred after pleading guilty to charges involving insurance fraud, Greenstein usually files his lawsuits without legal representation. “I would describe myself as a prolific plaintiff,” says Greenstein, author of the e-book Sue and Grow Rich: How to Handle Your Own Personal Injury Claim Without an Attorney. And he’s won some settlements and court victories.

In 2016, the California company Adams & Brooks was permanently enjoined from selling 4-ounce bags of P-Nuttles Butter Toffee Peanuts in the state after Greenstein sued in Orange County Superior Court, complaining that the company’s bags were 40 percent empty.

Greenstein was not awarded any money. “I get settlements, but they are not a lot of money,” he says, adding that money isn’t his main motivation. “When I see now how companies are just screwing over people with slack fill, … I figured I can do something.”

Silverman says many slack-fill lawsuits end in private settlements, with their details shrouded in secrecy. Few slack-fill cases have achieved class action status, but even the possibility of that happening is enough to scare companies into paying plaintiffs to go away, he says.

“These suits are just going to continue unless companies are willing to fight them out a little bit,” he adds.

But consumer advocate Dworsky says slack fill is a perfect illustration of why class actions are necessary. “No individual consumer is going to say: ‘I’m going up against Procter & Gamble because of the way they package this product.’ I mean, they have lost a dollar or two. But are they going to spend thousands on hiring a lawyer to make their point? You can only do it if you gather up people. You absolutely need consumer class actions.”

This article was published in the September 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title "Fill ’er Up!: Candy and snack companies sued for packages with empty space instead of extra product."