Bryan Garner shares brief-writing advice from the late Supreme Court Justice Wiley B. Rutledge

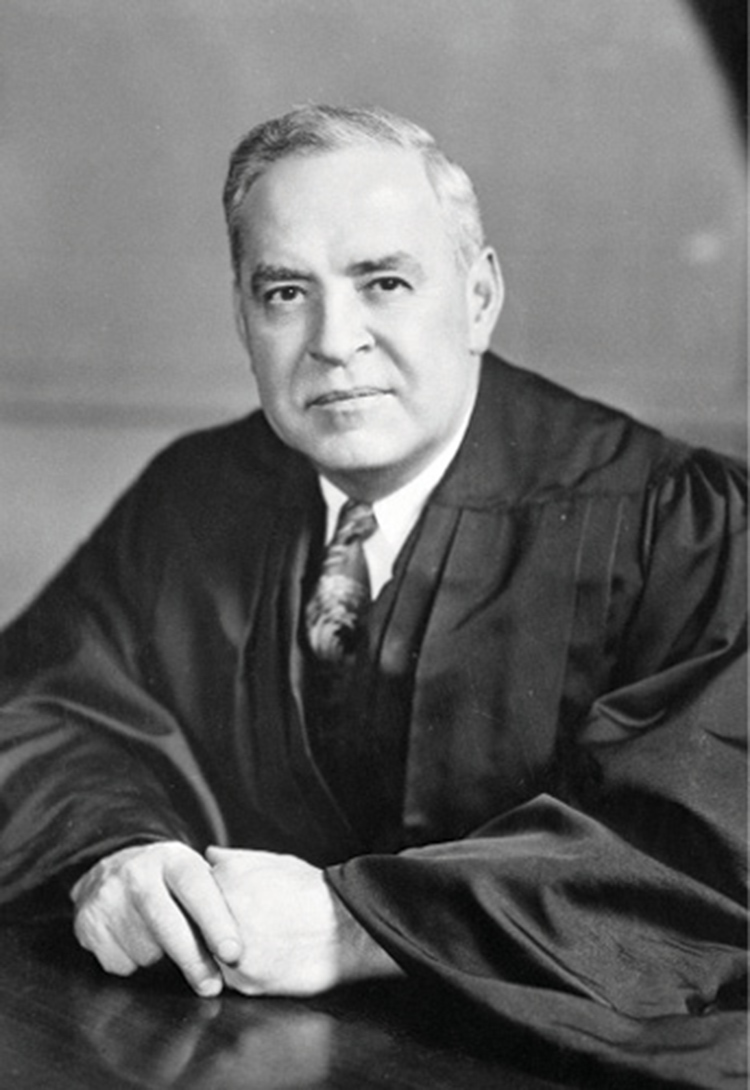

Photo of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Wiley B. Rutledge by AP Photos.

Readers of this column are familiar with my occasionally interviewing long-dead authors. Another name for it is active reading. Actually, we do it all the time—taking an author and interrogating the text for all the wisdom it might yield. In this space, I publish only the most notable of these interviews.

Today’s interviewee is U.S. Supreme Court Justice Wiley B. Rutledge (1894–1949), who had broad experience as a law teacher and jurist. He served as law dean at both Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Iowa. In the late 1930s, he supported President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s court-packing plan. In 1939, Roosevelt appointed him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and four years later to the Supreme Court—where he was known as one of the more progressive justices. Though Rutledge isn’t well-known today, he is often remembered as the justice for whom John Paul Stevens clerked in the late 1940s.

In fact, when I interviewed Justice Stevens in person at the Supreme Court in February 2007, we had the following exchange, published by the Scribes Journal of Legal Writing a few years later:

BAG: Five years before you clerked for Justice Rutledge, he wrote [an] article on appellate brief-writing—which I’ve always thought was excellent—in which he argued that it’s important for briefs to be interesting. Do you remember that article?

JPS: No, I don’t.

BAG: And did he have his clerks read that?

JPS: No, he didn’t. I don’t remember it at all. … His opinions were very long. He wrote opinions which many people thought were longer than necessary, but it was part of his feeling about the job—that you had to be fair to the lawyers and explain everything. And he was a very, very thorough workman.

So I decided to look it up and reread Justice Rutledge’s article—gently interrogating him as I went. “The Appellate Brief” originally appeared in the April 1942 issue of the ABA Journal.

Do you have any rules for brief-writing?

Briefs are as varied as the lawyers who make them and the cases with which they deal. Consequently, there can be no rule of thumb for writing them. But with the variables of author and case, there are recurring patterns and some constant elements.

You sometimes invoke Chief Justice Harlan Stone’s idea that the purpose of an appeal is to determine whether “one or the other of the parties has been ill-used under the law.” How is that best done in a brief?

The brief has several functions. Its basic one is to get to the court the lawyer’s picture of the facts, analysis of the issues and application of the law. If it does this, he wins.

Are you bothered when the opposing lawyers have widely divergent statements of the facts?

The bulk of the evidence is not controversial. … I suspect it would be as much so to the lawyers as to the court if in every case they would approach the appeal in the spirit of the question, “How much can we agree upon?” rather than “How much can we fight about?”

How detailed should a fact statement be?

[The lawyer] can freely and truly summarize. This often, and especially when well done, may be the most helpful, if not also the most important part of the brief. It cuts the brush away from the forest; it lifts the judge’s vision over the foothills to the mountains. It enables him to read the record with an eye to the important things, intelligently, in true perspective.

How should advocates deal with adverse facts?

Few things add strength to an argument as does candid and full admission, whether as to facts or law, of the factors which are clearly against one. When this is made, judges know that the lawyer is worthy of full confidence, and every sentence he utters or writes carries force from the very fact that he makes it.

Are citations to the record important to you?

Mechanically, I have only one suggestion in respect to the factual portion of the brief: That is for accurate reference to the appendix (or record) for every statement of fact. The statement is worth that if it is worth making, and doing it is a great time-saver for judges.

How important is issue-framing?

I regard it as next in importance to stating the facts accurately, sufficiently and succinctly. If the real issues are not drawn out, or this is done only confusedly, the remainder of the brief becomes almost a total loss.

Should the number of issues be pared down?

When a judge finds a brief which sets up from 12 to 20 or 30 issues or “points” or “assignments of error,” he begins to look for the two or three, perhaps the one, of controlling force. Somebody has got lost in the underbrush. … I strongly advise against use of this type of brief, consciously or unconsciously. Though this fault has been called overanalysis, it is really a type of underanalysis.

But what if there really are four or five issues that the lawyers want to bring?

If the case presents several issues regarded as important, it aids to indicate which are thought the more important. Again, this is a matter of emphasis for the brief.

In the meat of the argument, if I understand you correctly, you think advocates should argue on principle as much as on precedent.

Perhaps my own major criticism of briefs … would be the lack of discussion on principle. Some cases are ruled so clearly by authority, directly in point and controlling, that discussion of principle is superfluous. But these are not many. It has been surprising to find how many appealed cases present issues not directly or exactly ruled by precedent. That is as it should be. … In a large percentage of cases, therefore, there is room for discussion and thought as well as for citation.

You’re saying too many advocates just argue from precedents without showing the reasons they should control the outcome of the case at hand?

What judges want to know is why this case, or line of cases, should apply to these facts rather than that other line on which the opponent relies with equal certitude. … Too often, the why is left out. The discussion stops with assertion that this case or line of cases rules the present one. Assertion is not demonstration.

Your most famous law clerk, John Paul Stevens, suggested that your own writing can seem lengthy. Is that a problem with lawyers?

Be brief, that is, concise—but not too brief. By this is meant being as brief as one can consistently with adequate and clear presentation of the cause.

What do you think of legalese?

Avoid as much as possible stilted legal language. … Use English wherever you can express the idea as well and as concisely as in law or Latin.

Thank you for your time, Justice Rutledge. Any concluding thoughts?

All that has been said comes down about to this: Make your briefs clear, concise, honest, balanced, buttressed, convincing and interesting. The last is not least. A dull brief may be good law. An interesting one will make the judge aware of this.

This story was originally published in the February-March 2022 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Be Clear: Supreme Court Justice Wiley B. Rutledge offers posthumous brief-writing advice.”

Bryan A. Garner is the author of The Winning Brief (3d ed. 2014) and many other books about law, the editor-in-chief of Black's Law Dictionary and the president of LawProse Inc. Follow him on Twitter: @BryanAGarner This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.