Accusations of systemic racism at the highest ranks of the NFL have plagued the league for decades. After the racial unrest of 2020, sports teams promoted their efforts to address problems through acts that proved more symbolic than effectual. But as is often the case, legal action rather than moral imperative is being used to try to effect change.

The threat of litigation preceded the implementation of the Rooney Rule in 2003, after the widely questioned firings of two Black head coaches in January 2002. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers’ Tony Dungy was fired after a winning season; the Minnesota Vikings’ Dennis Green was let go after his first losing campaign in 10 years. Their dismissals left the NFL with just one Black head coach—a number that hasn’t moved much.

The Rooney Rule was implemented after a 2002 study by attorneys Johnnie Cochran and Cyrus Mehri that criticized the NFL for not giving Black head coaches equal opportunities. The diversity policy mandates that organizations must interview ethnic minority candidates for coaching and front-office positions, with the goal of solving racial inequity in the top ranks. In March 2022, the Rooney Rule extended its diversity efforts, requiring all teams to employ a “female or a member of an ethnic or racial minority as an offensive assistant.”

Twenty years later, the Rooney Rule has done little to break the NFL glass ceiling that’s blocked Black coaches from ascending. But where policy has left a vacuum, litigation is filling the void: The league’s lack of head coach diversity is now the subject of a class action lawsuit. Former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores (now a linebackers coach for the Pittsburgh Steelers) filed suit in February 2022, alleging the NFL and its 32 teams discriminated against Black coaches in the hiring process. Two other coaches joined the lawsuit in April: Ray Horton (retired) and Steve Wilks (who started the 2022 season as defensive passing game coordinator for the Carolina Panthers and was named interim head coach in October). The filing of the suit puts the league’s track record of hiring and treatment of Black head coaches under intense scrutiny. In a sport where 70% of the players are Black, there are only three Black head coaches at press time: Mike Tomlin, who’s been with the Steelers since 2007; Todd Bowles with the Buccaneers; and Mike McDaniel, who is biracial, with the Dolphins. The Houston Texans fired Lovie Smith in January.

“You could look year by year, and there have been some years where there’s been some increase in minority hirings,” says David Gottlieb, one of Flores’ lawyers, during an interview with the ABA Journal. “Going into this off-season, there were fewer Black coaches in the NFL than there were when the Rooney Rule was put into place. I think the overarching answer to that question is just that it hasn’t worked.”

In the suit, Flores and his legal team highlight the chasm between Black coaching and executive representation and Black player participation. From the general manager spot to quarterbacks coach jobs, Black candidates are not hired at a rate representative of the sport’s racial makeup. There are currently no Black majority owners in the league; however, Starbucks Independent Board of Directors Chair Mellody Hobson and former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice became part of an ownership group that purchased the Denver Broncos in August.

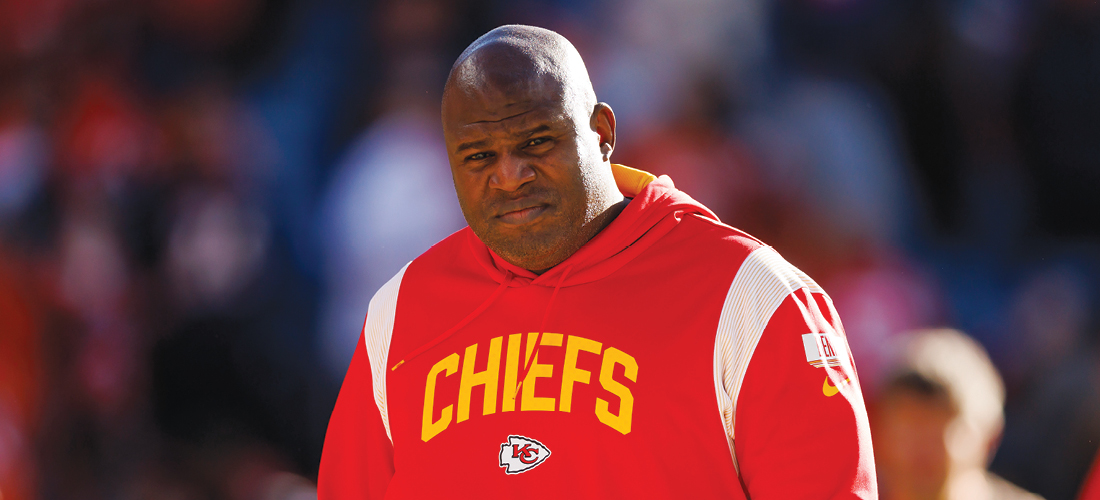

For decades, there’s been a pattern that shows a disconnect between the candidate pool and the resulting hires. Each season, Black candidates apply or are paraded as potential candidates for head coaching vacancies, then passed over—like Kansas City Chiefs offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy, who has been touted as a potential head coach option for the past five years. He’s been in charge of one of the best offenses in football since 2018, which is a prime position for a head coaching opportunity. In the previous four head coaching cycles, Bieniemy has interviewed with 15 teams, yet he remains in the same position.

“It’s been the worst-kept secret in terms of the Rooney Rule not being as successful as it could be,” observes Lauren Coffey, assistant professor of sport management at Winthrop University, where she focuses on sports law, discrimination and athletes’ rights. “Sports media has talked for years about why Eric Bieniemy, the offensive coordinator for the Kansas City Chiefs, wasn’t getting a head coaching position while others who were getting positions were not as accredited as he was. So it seems as though there’s always been a problem with the NFL when it comes to having people of color in positions of leadership.”

Flores’ complaint was prompted by negative experiences, including his interview process with the Denver Broncos in 2019 and the New York Giants in January 2022 and his tenure with the Dolphins from 2019-2022. It is two issues, the lawsuit says: the allegation of sham interviews in which Black coaches aren’t receiving real consideration; and their conspicuously shorter coaching tenures compared with those of white head coaches.

“When you go into a job interview, it’s presumably an opportunity to obtain the job,” Gottlieb says. “It’s a sham if the person does not have any chance or a legitimate chance. There are some situations where a hiring decision might have already been made, as we believe with Brian Flores interviewing with the Giants. There are other situations where a decision hasn’t been made, but the team still has pretty much made up its mind already: ‘We’re not interviewing this person because we’re genuinely considering them for the job; we’re interviewing them just to check the box off and comply with the Rooney Rule.’”

The NFL and the teams accused by Flores released statements disputing his factual allegations and denying they have engaged in discriminatory hiring practices. But Flores alleges that for his interview with the Broncos, John Elway and Joe Ellis, then the team’s general manager and president, respectively, showed up an hour late and conducted an interview lacking in substance, conveying the feeling that the team was not legitimately considering him for the head coach position. Instead, the Broncos hired Vic Fangio, who is white.

The Giants’ selection process was an even more blatant example of pretext by an organization with no intention of making a minority hire. Flores says he received multiple texts from his former boss, New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick, congratulating him on winning the Giants job—but the messages arrived before he had interviewed for the position.

Flores asked Belichick to clarify who he believed he was texting—him or then-Buffalo Bills’ offensive coordinator Brian Daboll, who is white and had already interviewed. Belichick responded: “I double-checked & misread the text. I think they are naming Daboll. I’m sorry about that. BB.”

Neither the Broncos nor the Giants responded to the Journal‘s request for comment.

Flores’ allegations against the Dolphins span his three-year tenure with the team. The complaint lays out how Flores was fired after posting the team’s first back-to-back winning seasons since 2003. Flores alleges his refusal to “tank” (lose games on purpose to improve the team’s draft position) led to his firing. He claims owner Stephen Ross once offered him $100,000 for each game that the team lost in 2019, which Flores believed was part of a larger plan to put the draft ahead of team success.

Flores also said in his lawsuit that he was pressured to break NFL tampering rules to recruit a prominent quarterback, and that Ross even set up a meeting between Flores and the quarterback that Flores refused to participate in.

An independent investigation ordered by the NFL into the allegations of tampering and tanking concluded in August that Ross did express that the Dolphins’ draft position should go ahead of the team’s win-loss record, but that Flores did not allow this to affect his commitment to winning. However, the Dolphins, who did not respond to a request for comment, lost two draft picks after the investigation determined they had impermissible contact with quarterback Tom Brady and coach Sean Payton. Ross was suspended for two months and fined $1.5 million as a result.

The class action racial discrimination suit collectively names the NFL and each of the league’s 32 teams as defendants, a move intended to establish the league as a joint employer, Gottlieb says.

Plaintiffs also contend the NFL is complicit in the hiring processes of its teams, as they must adhere to the league’s bylaws, and Commissioner Roger Goodell can unilaterally rule on coaching contracts.

Legal experts say the NFL will argue it doesn’t have responsibility for the way individual teams make decisions; and each of the six teams named as individual defendants in Flores’ complaint has denied the allegations.

The league issued this statement in February 2022, after Flores’ suit was first filed: “The NFL and our clubs are deeply committed to ensuring equitable employment practices and continue to make progress in providing equitable opportunities throughout our organizations. Diversity is core to everything we do, and there are few issues on which our clubs and our internal leadership team spend more time. We will defend against these claims, which are without merit.”

“If they were a joint employer, that would be a detriment [to the league’s case] because it’d be saying the unwritten rules of the NFL are creating this situation,” Coffey says. “So the NFL is kind of in between a rock and a hard place situation here. Each of the 32 teams does exactly what they want to do. But we as the public view them as that joint employer because they set the rules that everyone is governed by. It’s going to be interesting because you could make the argument there is more that they could do to reinforce these rules since they set them.”

There’s precedent for the NFL to do more to enforce the Rooney Rule. Coffey points to the only instance of league-mandated punishment for violation of the mandate: Shortly after its implementation in 2003, Detroit Lions President Matt Millen was fined $200,000 for failing to interview any minority candidates before hiring Steve Mariucci as head coach in February of that year. The Washington Post reported that Millen claimed he did not interview minority candidates after firing team coach Marty Mornhinweg because they declined to interview for the job, believing it was certain Mariucci would be hired. Millen’s explanation relies on a discriminatory paradox: If Black coaches don’t interview for head positions, perhaps it’s because history has proved there’s almost no chance they’ll be hired.

Flores’ initial complaint describes the NFL as being a racially segregated organization “managed much like a plantation” with Black coaches continually passed over for top positions while the “32 owners—none of whom are Black—profit substantially from the labor of NFL players … who put their bodies on the line every Sunday, taking vicious hits and suffering debilitating injuries to their bodies and their brains while the NFL and its owners reap billions of dollars.”

According to the language in the class action complaint, Flores is seeking to force the NFL to make changes in the way its teams hire coaches and executives, and even appoint an independent monitor for oversight. Among other forms of relief, he wants to promote Black ownership of NFL teams; increase objectivity and transparency in hiring and termination decisions for top positions; increase the number of Black offensive and defensive coordinators, which in turn creates a stronger pipeline for them to become head coaches; and incentivize the hiring and retention of Black candidates for these positions.

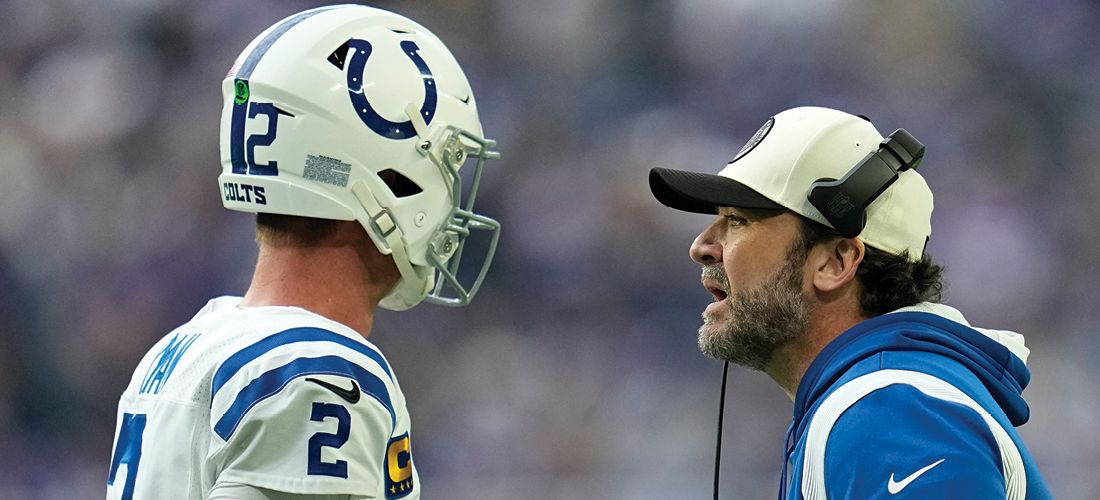

In addition to his own experiences, Flores points to other Black coaches’ histories to demonstrate a pattern and practice of racial discrimination by NFL teams during the hiring and termination process. He cites former head coach Jim Caldwell and his firings by the Indianapolis Colts and the Detroit Lions despite multiple winning seasons. Neither team responded to a request for comment.

While working for the Lions, Caldwell completed three winning seasons out of four but was fired in 2017 after the team went 9-7, and replaced by Matt Patricia, who is white. Patricia posted a winning percentage of .314 in his three seasons as head coach there.

Flores also describes David Culley’s experience during the 2021 season, in which he was hired as head coach for the Houston Texans and fired after a season in which the team lost multiple top contributors before he had the chance to coach a game.

Culley, who coached 28 seasons in the NFL, was fired over “philosophical differences,” according to a statement from Nick Caserio, the Texans’ general manager.

Flores’ lawsuit alleges the NFL and its teams violated state and federal civil rights laws. His legal team is also pursuing claims under Title VII and has initiated proceedings through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Proving disparate treatment in a Title VII case can be an uphill battle, says Alicia Jessop, associate professor of sports law and sports marketing at Pepperdine University and founder of the media brand Ruling Sports.

“The reason for that is that [plaintiffs] have to prove intentional discrimination. What that would look like in this instance is an NFL owner or executive intentionally determining not to hire someone because of that person’s membership in a protected class, which in this instance is race.”

"The case is bigger than just Brian Flores. It's about the way their colleagues have been treated over the years and continue to be treated." —David Gottlieb

Jessop says employers have become skilled at masking intentional discrimination when they want to hide it, creating a burden that can break a case. But Flores could also argue the NFL’s hiring practices had a disparate impact because its effect excluded an excessive number of qualified Black applicants, in violation of equal protection laws. Jessop points to the common NFL practice of hiring head coaches who have experience as quarterbacks coaches or as offensive, defensive or special teams coordinators—positions that also have a diversity chasm. At the time Flores’ complaint was filed, there were just four Black offensive coordinators in the league, three Black quarterbacks coaches, and 11 defensive coordinators out of 96 jobs—restricting the pipeline for inclusive hiring.

But Black NFL coaches feel subjected to a double standard, experience or no experience. Eyebrows were raised across the league in November when former Indianapolis Colts center Jeff Saturday was named the team’s interim head coach midseason, with no professional or college head coaching experience. He had only previously coached high school football. (The Rooney Rule does not apply to interim head coaching positions.)

In June, the NFL filed a motion to move the lawsuit to arbitration overseen by Goodell. In August, U.S. District Judge Valerie Caproni denied Flores’ request to take the case to discovery before she rules on whether the case goes to arbitration, which is an important step for the Flores team. On Oct. 7, plaintiffs counsel filed a motion arguing against the move to arbitration.

“One of the most significant outcomes of this case would be if the discovery process is allowed to commence,” says David Lopez, a professor at Rutgers Law School and the longest-serving general counsel of the EEOC. “It would allow for communicative materials, like emails and text messages, to be obtained and reviewed. It would allow for the deposition under oath of various officials to be taken. What could emerge is a greater understanding of why in the 20 years of existence of the Rooney Rule, there have been less than 20 Black men hired to head coaching vacancies.”

If Caproni grants the NFL’s request for internal dispute resolution, the case would move behind closed doors with the league choosing an arbitrator. The Flores team claims the NFL is attempting to “avoid public scrutiny of the racial discrimination and claims we have brought” and insists the case should remain in open court to increase transparency.

“The purpose of this lawsuit is really to create change within the NFL and to make sure that discrimination does not happen going forward with respect to the way coaches are hired, how they’re treated and how they’re terminated,” Gottlieb says. “The case is bigger than just Brian Flores. It’s about the way their colleagues have been treated over the years and continue to be treated. They’ve brought the case on behalf of not only themselves but everybody who has suffered discrimination the way they have.”

If successful, the case has more potential to open doors for Black and other minority coaches in the NFL than any league-based initiative could. Flores’ complaint has prompted additional scrutiny about the way the NFL operates and its true commitment to diversity and inclusion. There’s precedence for this increased attention, with the league under pressure for its history of discrimination issues at the player as well as coaching level. Quarterback Colin Kaepernick received backlash and has been unable to find employment with the league after he knelt for the national anthem to draw attention to police brutality and social injustice.

And in 2021, the NFL settled a lawsuit with Black retired players, paying out $1 billion for concussion claims and promising to end the practice of “race-norming” their brain testing protocols, which caused Black players to be paid out less than their white counterparts. Now, with allegations of sham interviews, “boys club” hiring and discriminatory practices at the highest levels, Flores’ claims are just the latest accusations of diversity failures at the NFL, which persist despite all the social justice gestures and “End Racism” messages spray-painted on the field.