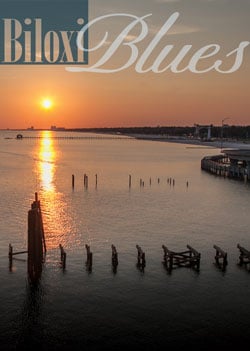

Biloxi Blues: Legal-Cost Fears Have Victims of the Oil Spill Sliding out of the Middle Class

Photos by Kathy Anderson ©2012

That was it. Nothing more could be done. Two years after the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon, Tina Copeland’s American dream was over. Her Mississippi Gulf Coast business was hemorrhaging funds, her marriage torn apart.

Though billions were offered to settle damages from the April 2010 disaster, the formal process she faced devolved into a prolonged battle with administrators over the legitimacy of tax records, of financial documents and of letters from lost clients saying they could no longer afford Copeland’s day care service because of diminished wages of their own. Always something was said to be missing from her file. By the time her claim was finally denied, Copeland had given up hope. “I had no idea of what to do,” she says, “no idea there was another option.”

A soft-spoken, dignified woman, her diction is clear and her voice warm. She picks at the lace tablecloth in her stuffed-to-the-rafters apartment that now holds what was once spread through her Long Beach, Miss., house. And speaking of what she had and lost, she cries. She doesn’t sob or weep uncontrollably, but her voice catches, as if she is embarrassed to be crying—and even more embarrassed to be in this position.

Asked why she didn’t seek the advice of a lawyer to save the company she’d founded nearly 25 years ago, she shakes her head: “Oh my God, I can’t even imagine,” unable to fathom a cost she assumes would have been insurmountable.

Copeland is one of hundreds of thousands of claimants along the Gulf Coast still seeking compensation from a complex settlement system. But she’s also part of a larger group of working and middle-class Americans besieged by sudden reversals of fortune in the wake of the Great Recession—whether by natural disasters, foreclosures, bankruptcies, collections, employment disputes or simple domestic relations issues.

Video featuring Gulf Coast residents.

These middle-class households, with annual income from $39,000 to $118,000, have suffered the “worst decade in modern history,” the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center reports.

Yet an apathy—even antipathy —toward their plight persists. When Miami lawyer Kendall Coffey suggested in a recent National Law Journal column that unemployed law graduates could “earn decent compensation and launch successful practices” by charging $50 to $125 per hour for these underserved clients, the response from commenters on ABAJournal.com was hostile. In scores of comments to the post, these moderate-income Americans were cast as deal-hungry, do-it-yourself folk who simply refuse to pay the traditional hourly rates of the private bar, more undeserved than underserved.

In truth, the median income of American households dropped last year to its lowest level since 1995. A record 2.87 million properties received notices of default, auction or repossession in 2010. About 4.76 million homes have been repossessed since the housing boom ended in 2006, and unemployment hovers around 8 percent. As the collective wealth of more than half of America’s adults continues to diminish, their legal problems swell.

Most will have some sort of interaction with the legal system in their lifetimes. With dwindling savings and vanished home equity, a significant and increasing number will do without legal representation. For Copeland and many moderate-income residents—who earn too much to qualify for free legal assistance but can’t afford lawyers —the delivery of justice has become a nearly unattainable goal.

While the situation in the Gulf region has created a perfect storm that threatens to strain the civil justice system almost to the breaking point, the same problems are chipping away at moderate- and middle-income Americans case by case, day by day within dozens of state and federal judicial systems.

Lack of access to legal services complicates problems for both common citizens and the courts, yet efforts to bridge the gap between needs and services don’t seem to be working. For them, justice faces a variety of obstructions: a haphazard patchwork of legal aid and social service providers contending with cutthroat competition for funds, a growing distrust of the private bar, a court system too complicated for pro se litigants, and the constant reality of prohibitive costs.

Tina Copeland has had to deal with copious amounts of paperwork in her quest for reimbursement. Photos by Kathy Anderson.

TINA’S STORY

Tina Copeland started her own day care service with a partner when her now-college-age daughter was 2 years old. She’d become the company’s sole proprietor and cared for 47 young children at the preschool she built a few miles from the waterfront.

Many of her charges, some of whom had been with her since birth, were the children of neighbors and friends who, before the spill, were shrimpers, fishermen or boat crew, or were employed at one of Biloxi’s many flourishing, tourist-driven casinos.

Two years later, polluted waters remain devoid of sea life, tourists and locals. The economic implosion that ravaged those on the water steadily creeps inland. Casinos, hotels, restaurants and other businesses have slashed budgets and laid off staff along hundreds of miles of coastline.

At Copeland’s preschool, absences slowly snowballed into nearly a quarter of the total enrollment. Unemployed parents struggling to buy groceries and make mortgage payments could not and still cannot afford child care.

“We’ve had our ups and downs, but I’ve always been able to keep the business going,” Copeland says. “It’s all I’ve ever known—until now.”

Because her business was tied to the declining prosperity of the community rather than the Gulf directly, Copeland didn’t file a lost-income claim with the Gulf Coast Claims Facility until nearly five months after the spill.

She is one of thousands of moderate-income claimants to file months after the disaster’s initial impact, who now seek compensation from the complicated and adversarial BP settlement process constructed in March, the second large-scale effort to provide restitution to those affected by the spill.

The first, overseen by Ken Feinberg, the government-appointed czar of the BP Deepwater Horizon Disaster Victim Compensation Fund, received harsh criticism for his firm’s eye-popping lawyers’ fees, questionable payouts and allegations of pressuring claimants to give up their right to sue.

For months Copeland wrangled with claim administrators over proper documentation during dozens of phone calls and 10 six-hour in-person visits to the Gulf Coast Claims Facility.

“You never had the right stuff,” Copeland says, with ragged frustration apparent in her voice. “No matter what documentation I brought back, it was never the right stuff.”

Finally, the letter arrived, brief and generic: “Ms. Copeland: We regret to inform you … .”

“There was no information explaining why it was denied,” Copeland says. “There was nothing.”

Embarrassment over her ignorance of the right to appeal is evident as her voice trails off. But she is not alone.

Judges across the country struggle daily to preside over cases where a significant number of confused self-represented litigants misinterpret the law or fail to present key pieces of evidence, says John Levi, board chairman of the Legal Services Corp.

“When roughly 20 to 40 percent of the population feels that the only way they can handle an issue is to show up and try to represent themselves, that puts an enormous amount of strain on the courts,” Levi says, citing recent judicial surveys.

“The rules of evidence and procedure are daunting enough for practitioners. The complexities of bankruptcies, foreclosures, evictions, family law and other issues faced by clients of LSC funding programs are challenging even to most lawyers not specially trained in those areas. They must be utterly unfathomable to self-represented litigants.”

For Copeland and many like her, unknown rights prompt inaction. Inaction gives rise to dire financial circumstances. Yet if she had been advised of her legal right to appeal the denied claim, would she have sought the services of a lawyer?

“Oh, no,” she says, “I couldn’t go out and hire an attorney.” There is no trace of doubt in her response.

Copeland’s struggle for redress eventually took tolls on her marriage and her health. She has moved out of her former home. She lives alone in an apartment and is an hourly employee at the business she was forced to sell a few months after she received the denial notice. Copeland and her husband remain unable to deal with family matters, paralyzed by financial uncertainty.

Legal aid lawyers Stephen Teague, Charisse Gordon, John Jopling and Khiedrae Walker are helping more moderate-income clients since the spill. Photo by Kathy Anderson.

LEGAL AID, BUT LATE

John C. Jopling, managing attorney of the Mississippi Center for Justice’s Gulf Coast office, now represents Copeland’s lost-income claim at no cost. The Gulf Coast Claim Facility has been dismantled and, under the terms of the March settlement, a new system run by attorneys and overseen by the courts has been set up for people and businesses whose claims were denied or never paid. The Settlement Authority now funds the Gulf Justice Consortium, a 16-lawyer, multistate collaboration among Gulf Coast legal aid organizations to assist oil claimants. The effort was spearheaded by Mississippi Center for Justice President and CEO Martha Bergmark in the immediate aftermath of the disaster.

“We knew there would be huge disruptions to people’s wages and incomes, and they’d be facing pressure on home mortgages and other bills,” Bergmark says. “There is a microcosm along the coast of the worst possible experiences for folks well up the economic ladder, or who used to be and may now be the new poor. They are people who never expected to experience this kind of inability to deal with legal problems that are very serious.”

Located in downtown Biloxi, the center bills itself as a homegrown, nonprofit public interest law firm. While its mission includes combating racial and economic injustice in the poorest state in the nation, Jopling and his staff attorneys have seen a staggering influx of moderate-income prospective clients in the wake of the spill. He says 50 percent of their oil claimants are of moderate income.

Most are blocked from receiving free, federally funded legal aid by income requirements that restrict services to those at or just below the poverty level. Yet the ability to front a retainer fee for a private attorney, often thousands of dollars, is unthinkable to them.

Even for matters taken on a contingency basis, the sheer number of hours required by a lawyer to handle certain matters often doesn’t economically justify the pursuit of smaller five-figure claims. As a result, claimants are turned away, though for many in the Deep South, a claim that size amounts to several mortgage payments.

Michael Joyner—with sons (L to R) Kanton, Kaleb, and Kole—lost half his income after the oil spill. Financial woes forced Joyner to move his family from a spacious house to a small apartment. Photos by Kathy Anderson.

Michael Joyner, a married father of three young boys, is another client of the Mississippi Center for Justice receiving free assistance through funding from the BP settlement administrators. Joyner’s body reflects his life of physical labor, but his words display the frustration and helplessness he feels about a situation he’d like to take in hand, but can’t.

Before the oil rig explosion, Joyner maintained a beverage distribution route along the 20-mile stretch of coastline from Biloxi to Pass Christian for PepsiCo. When his $45,000 annual salary was halved because his customers’ demands dried up along with the Gulf’s tourism industry, Joyner found part-time work at a local construction company. Months later, he was forced off the job by a back injury.

Ashamed that he could no longer support his family and afraid that his right to redress might be viewed as a demand for an undeserved handout, Joyner hesitated to seek legal counsel. He also worried that any payment received from a lost-wages claim could be recalled, which happened to friends who’d received insurance money in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

“After Katrina, everyone was running anywhere they could to get money,” Joyner says. “After the smoke cleared, a lot of them had to pay some of that money back” for erroneously paid insurance claims.

“I wasn’t going to go down to the [claims office] myself and [file] because, to me, it wasn’t worth the risk of making a mistake. To owe $20,000 … can bankrupt a family, ruin people’s lives. If you never had it to begin with is one thing, but if someone gives you money and then wants it back—even $10,000. I can’t risk my family for that.”

Embroiled in a workers’ compensation claim for his back injury—the first time he’s ever hired an attorney—Joyner reluctantly moved his wife and sons out of their five-bedroom home and into a two-bedroom, sparsely furnished apartment to cut costs.

By chance he saw a billboard with a phone number for commercial fishermen seeking legal help. The Vietnamese fishing community has been purposefully targeted by out-of-state and local members of the private bar as lost-wage claims can approach six figures, more than for many of the small-business owners along the coast.

Desperate for any guidance, Joyner called the number and was referred to the Mississippi Center for Justice. He now has a contingency-based workers’ comp attorney, in addition to Jopling’s free services.

Joyner’s only inkling about lawyer rates stemmed from a buddy’s hunting mishap. “For somebody that makes $40,000 to $50,000 a year, if you drop $4,000 to $5,000 on a lawyer, that’s 10 percent of what you’ve made for the entire year. Most people don’t have that kind of money around here.”

Legalese also hinders Joyner’s ability to be an active client—one who fully grasps his rights and the justice process. “I’m educated, but with legal terms it’s like speaking another language,” he says. “The workman’s compensation forms will say the same thing in 10 different ways, but I still don’t know what they are saying. The better way to do it is with someone who has gone to school and is educated on how to read the forms.”

Most moderate-income Americans are not sophisticated consumers of legal services. And, in many instances, the issue or catastrophe at hand is a person’s first-ever interaction with a lawyer.

Felicia Williams-Reynolds: “If I’m only going to get back what I lost, and … pay the attorney 33-40 percent, where is that going to leave me?” Photo by Kathy Anderson.

THE COST OF DISTRUST

For single mother Felicia Williams-Reynolds, a bad prior experience and distrust of the private bar discouraged her from seeking a lawyer’s advice when her income plummeted from $60,000 to $20,000 in the aftermath of the spill.

Her well-gelled hairstyle is courtesy of students at a local technical college; her nails are home-manicured. Her character is resilient. She has taken more than a few hits and bounced back up to fight. But the fight goes on.

Williams-Reynolds worked as an operations clerk at a military base where her hours fluctuated from 20 to 40 a week. She supplemented her income with a part-time job at Wal-Mart after being laid off from a full-time job with FEMA in 2009. Her shift at Wal-Mart began at 5 p.m., a typically busy time for the superstore, since a large number of customers would stop in after the workday to pick up groceries and other household items. Eventually, as cashiers stood at empty registers and shelves remained fully stocked, Williams-Reynolds saw her hours cut drastically.

“I knew the oil spill had happened, but I’m the type of person, I like to wait and see what the full range of [impact] is going to be,” she says. “Then I found out there were people at Wal-Mart who were getting reimbursed for their lost wages.”

Like Copeland, Williams-Reynolds was initially denied reimbursement of her loss claims.

“I was devastated,” she says. “I’ve lost all of this income. I need it. I don’t want bill collectors calling.

“I did [think about hiring an attorney] but I can’t afford it. If I’m only going to get back what I lost, and I have to pay the attorney 33 to 40 percent of that, where is that going to leave me?”

She contacted a federally funded pro bono legal aid organization, only to be told that at $10.75 an hour she earned too much to qualify for free services. Refusing to take no for an answer, she called the Gulf Coast Claims Facility daily until one phone operator reluctantly offered a small piece of advice.

“Finally a lady came on the phone and said, ‘We have a lot of people in the same category you’re in,’ ” Williams-Reynolds says. The operator told her about the pro bono lawyers at the center but cautioned: “I’m not supposed to tell you this; I’m just supposed to tell you to seek legal representation.”

Also in the midst of ending a volatile domestic relationship, Williams-Reynolds sought help from a string of family law practitioners routinely demanding a $5,000 retainer. The amount may as well have been $50K, she says. It wasn’t until she heard from a friend about a lawyer open to custom payment plans that she was able to proceed with her divorce.

As of September, the oil spill cleanup continues, with BP contract workers searching for and removing small gobs of tar on Horn Island, just off the coast of Biloxi. Photos by Kathy Anderson.

FEAR AND FINANCIAL STRAITS

Fear of exorbitant legal costs, real or imagined, prevents many Americans from seeking aid through the private bar—even if they’ve never spoken to a lawyer about rates. While more solo and small-firm practitioners offer adjustable rates (a major disconnect from traditional billing models), potential clients’ perceptions of attorneys, as well as their need for predictable costs and legal services in line with economic realities, can stop them from seeking legal assistance.

Meanwhile, lawyers have their own hurdles—the complications of lower income in less-prosperous areas and the high cost of legal education. And a law degree is no antidote to economic crises, especially in heavily affected areas.

“It is not a sound business approach long term for a lawyer to take a case that will only pay $500, yet may cost them 10 hours in work,” notes Adam Kilgore, general counsel for the Mississippi Bar. “Likewise, there is resistance from some lawyers who see pro bono as somehow potentially taking away paying clients because everyone is struggling. Yet, if they knew more about the specific case they would not be interested in taking it based simply on the economics.

“Both the Supreme Court of Mississippi and the Mississippi Bar continue to invest time and resources to encourage pro bono work from our lawyers in Mississippi, as well as empowering and protecting the public,” he says. “There is no simple solution, but the effort will and must continue.”

Those lawyers and firms who have clients willing and able to pay standard billing must decide whether they can take on needy clients at reduced rates. And whether they should.

“Is it fair for the high end to subsidize the low end?” asks Clay J. Garside, an associate at Waltzer & Wiygul, whose New Orleans firm offers a sliding-fee scale for some clients. “Are we living up to the ethical responsibilities to our higher-end clients?”

As more would-be consumer clients turn away from the private bar, cash-strapped courts face an increased strain from desperate, inexperienced self-represented litigants.

Even with state bar help, the courts are limited in what they can do.

“In 2011, the Louisiana State Bar Association created a help desk for self-represented individuals in New Orleans domestic courts at the request of judges with dockets with an overwhelming number of pro se litigants,” says John H. Musser IV, association president. “The Orleans Parish self-help resource center, which is staffed by pro bono attorneys who offer information and form documents prepared by the courts, has since expanded to three courtrooms across the state. … We’re seeing hundreds of people take advantage of the help desks.”

At the Mississippi Center for Justice, Jopling has become acutely aware of a hollowed-out middle class increasingly susceptible to any economic downturn that renders them unable to afford a lawyer and more likely to avoid dealing with legal issues until it’s too late.

“Based on my 10 years with a legal aid organization [from 1984 to 1994], that was definitely true to lower-income clients,” he says.

“I’m concerned that characteristics previously apparent among lower-income persons are now becoming characteristics—or symptoms—manifesting themselves among working class and middle class,” Jopling says. “These symptoms are moving up the income chain.”

Clarification

The feature “Biloxi Blues,” November, refers to an ABAJournal.com news summary that contains a quote from Miami lawyer Kendall Coffey. Although the reader comments referenced in the story appear in the ABAJournal.com webpost from Aug. 22, 2012, the original quote appeared in a National Law Journal article penned by Coffey on Aug. 15, 2012.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.