Aug. 12, 1998: Swiss banks settle Holocaust claims

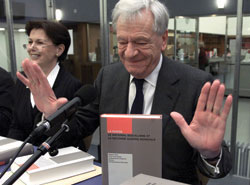

Photo of Jean-Francois Bergier by AP Photo/Keystone, Lukas Lehmann

More than 50 years after the collapse of Nazi power in Europe, important issues of life and property drawn from the Holocaust were still being litigated in U.S. courts. One of the most vexing involved foreign accounts created in Swiss banks by victims of the German regime. Following the war, efforts to recover these “heirless assets” were met with passive resistance or outright intransigence from a banking system valued for its neutrality and renowned for its secrecy. Swiss government-directed searches up through 1995 identified only 775 victim accounts from nearly 6.9 million foreign accounts created in Swiss banks between 1933 and 1945.

But beginning in 1996, a series of class actions filed against Swiss banking interests gained traction in a New York federal court, forcing Swiss bankers to agree to a much broader, more concerted effort to identify Nazi victim assets. An international commission headed by former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker supervised 650 forensic accountants who compiled data on 4.1 million foreign accounts from 254 Swiss banks for which there were records. These records were compared to the names of 5.5 million known victims of Nazi persecution documented in Israeli and U.S. Holocaust archives. After that, the accounts were analyzed by hand for potential relationships to victims.

Photo of Paul Volcker by AP Photo/Mati Stein

Meanwhile, another commission by Swiss economic historian Jean-Francois Bergier explored and reported on widespread Swiss involvement with Axis interests: as a financier of German armaments, a client for forced labor, and a harbor for gold and art objects looted during the German conquests of Belgium and the Netherlands. That report also condemned, in particular, the Swiss government’s adoption of racist restrictions on Jewish refugees before and during the European war, as well as the repatriation of thousands of refugees to Nazi-occupied countries where they faced almost certain extermination.

Even before the Volcker and Bergier commissions had completed their reports, the Swiss banks agreed to settle the claims against them. Under terms of the global agreement, verified “victims or targets of Nazi persecution”—defined as Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma, gays and the disabled—could make claims from a $1.25 billion fund provided by the banks. The settlement compensated victims not only for lost deposit assets but also for Swiss participation in slave labor, the trafficking of looted assets and race-based refugee policies.