Winning short story: 'The Attorney Helped Clean Up The Blood'

It was about three weeks after that when Tim presented his ideas about a gun to Neil.

“My grandma thinks it’s a bad idea,” Tim said. “But we need it. For protection.”

Neil weighed his thoughts carefully before answering, sipping his coffee.

“Well, Tim,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s a good idea or if it’s a bad idea. But what I do know is that you have a constitutional right to own a gun if you want to own a gun.”

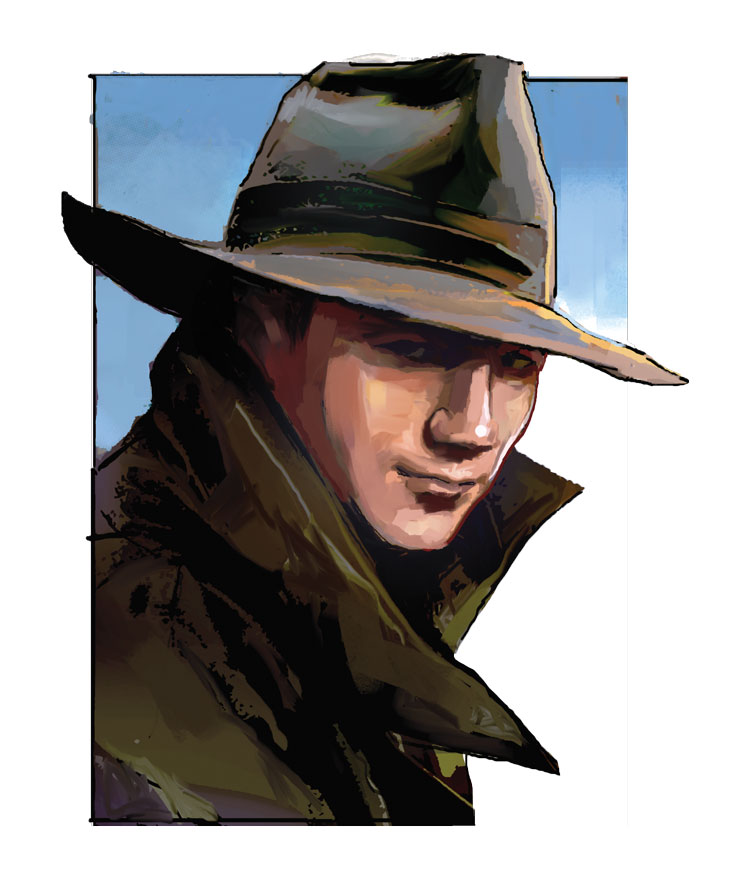

Illustration by David Owens

Tim lit up like the sun.

“And a permit to carry?” he asked. “Could I get a permit to carry?”

“Of course,” Neil said. “Almost anybody can.”

•

And so it went. Tim went to the gun shop and he bought a gun, and he got a permit to carry it. His grandma was not happy, but after all, the kid was 22.

“Just be careful, OK?” Neil said to Tim one day in early April.

“Oh, believe me, I have OCD,” Tim replied. “I check that the safety is on, like, a hundred times a day. And I empty the chamber before I hand it to anybody.”

“Good,” said Neil. “Excellent. Gun safety is a fine skill to have.”

He heard the sirens on April 9th, middle of the afternoon, Palm Sunday. Neil had been to church and was still in his dress clothes, feet propped, reading the paper. (Neil still subscribed to the newsprint version; he wasn’t one for electronic reading.)

At first, he semi-ignored the screams of the sirens, thinking that maybe there’d been a wreck out on the main road. But then it sunk into his consciousness that the sound was nearby. In fact, it was right outside of his house.

Neil folded the paper, carefully. He placed it on the end table in the usual spot. He stood up from the recliner, stretched, looked through the living room window. Despite his slow and normal movements, Neil’s heart was beating hard. He knew how to appear calm in any situation, how to fake peace when he was shook up.

Cops and medics and an ambulance were racing up the lane, right next door on Orchard Road. They were going up to Tim’s house.

•

The kid who shot him was only 19. At first he claimed that Tim was trying to commit suicide, that he’d pointed the gun to his head and it went off. But then he changed his story, later that night, in the state police barracks. They took him in, to the prison, locked him up.

The bullet hit Tim in the head, left him with a gaping hole where his forehead used to be. He was brain-dead by midnight. Neil wailed, sobbing harder than he’d cried in a long, long time.

The kid died by Monday afternoon. His organs were donated. There was no more Tim, no more grin, no more visiting kid with the loud laugh.

The autopsy results were released on Tuesday. Tim had been shot from across the room, by his own gun. The 19-year-old, Alex, was arraigned. It made the front page.

Neil sunk into the depths of despair. He hated that he’d even given Tim any advice. He hated that Tim followed his advice. Neil wished he could rewind the day of April 9th, make it all different.

But he couldn’t. Of course he couldn’t.

And so he helped to clean up the blood. He and a few farmers from Orchard Road sent the grandma out of the house, ripped up the still-wet blue carpet, threw it into a dumpster. They scrubbed and scrubbed the hardwood floor beneath, but the stains would not go away.

The shape of the blood remained.

•

Alex’s mother called Neil Blastman, asked if he’d represent her son pro bono. Or if not that, maybe at a reduced rate. She couldn’t afford much, was a single mom who lived in the trailer park.

“They were arguing over a video game,” the mom said, crying. “A stupid, damn video game.”

Neil didn’t have to consider. He didn’t have to think. He followed his gut and the words tumbled out of his mouth before he knew what was happening.

“No,” he said. “No. Thank you for calling, though. Thank you for thinking of me.”

Neil Blastman was always polite. His mother had taught him right.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.