Arizona law determines fate of frozen embryos in divorce cases

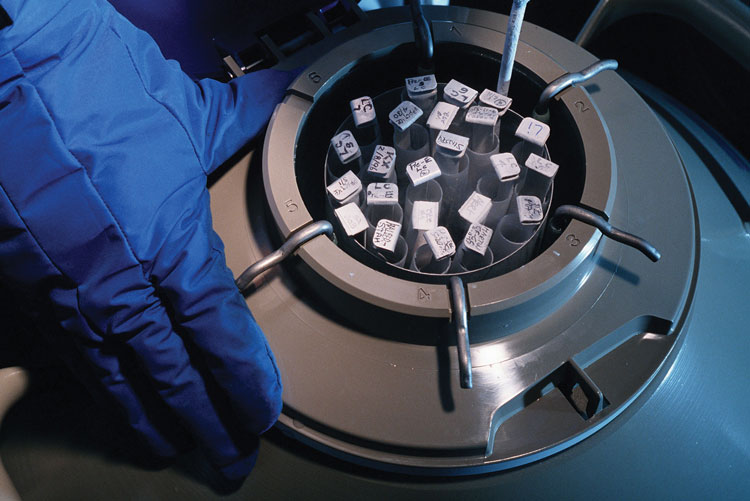

Photo by Carolyn Van Houten/The Washington Post via Getty Images.

For more than two decades, state courts have wrestled with how to settle disputes over frozen embryos when couples divorce or otherwise split. In such cases, one spouse typically wants to keep the embryos to eventually conceive children, while the other doesn’t.

Courts have tended to side with the party who doesn’t wish to be-come a parent on the grounds that no one can be forced to procreate. But at times, rulings have gone the other way—especially in instances where the frozen embryos represent a person’s only chance of having biological children—leaving a split in the courts and uncertainty for litigants.

Judith Darr: “Each state has tehir own public policy. There’s no uniform approach.” Photo courtesy of UCI Law.

But a first-of-its-kind law would end that uncertainty in Arizona. The state’s Parental Right to Embryo law, which took effect in July, requires courts in divorce proceedings to award in vitro embryos to the spouse who intends to allow them to “develop to birth.”

Courts have generally viewed embryos as property—if property deserving of special respect—but not as people. Abortion-rights proponents view the law as “backdoor right-to-life” legislation aimed at establishing embryo personhood.

Despite accusations that the law is an attempt to give rights to embryos, architects of the legislation claim the main intent is to benefit future parents. “This new law strikes a balance between the interests of both spouses. One spouse can have the embryos for the purpose of having children, and the other spouse has no obligation as to any resulting child,” says Michael Clark, vice president of policy and general counsel at the Center for Arizona Policy, a nonprofit conservative advocacy group that helped draft the law.

Arizona legislators introduced the bill in response to the case of Ruby Torres and John Terrell, a Phoenix couple who completed in vitro fertilization before Torres underwent cancer treatment so they could later have children. A preconception agreement mandated neither could use the embryos without the other’s consent.

When Terrell filed for divorce in 2016, Torres sought to keep the embryos, arguing it was the only way she could have biological children. Terrell told the court he did not want to have children with Torres.

Based on their agreement and other evidence, the court ruled Torres had no right to use the embryos. The judge ordered them to be donated. Torres appealed the decision, and a ruling is pending following oral arguments in June. Arizona’s Parental Right to Embryo law can’t be applied retroactively and shouldn’t affect the case.

Ruby Torres in her apartment complex in Phoenix. Photo by Remi Banali/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

The law hasn’t yet been challenged, but Richard Vaughn, founder of the International Fertility Law Group in Los Angeles, questions its constitutionality. “Based on existing Supreme Court jurisprudence, it would fail because it forces procreation,” he says.

According to Judith Daar, a visiting professor at the Univeristy of California at Irvine School of Law and clinical professor at Irvine’s medical school, federal legislation on the issue is unlikely because family law matters have historically been governed by state law.

“Each state has their own public policy. There’s no uniform approach,” says Daar, who also chairs the ethics committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, which opposed the new Arizona law.

To bring clarity to the issue, Vaughn and other members of the ABA Family Law Section’s Assisted Reproductive Technologies Com-mittee (of which Vaughn is immediate-past chair) have formed a subcommittee to explore model legislation addressing the disposition of disputed embryos. When and if completed, states could use the group’s work for guidance. But Vaughn admits that process could take years.

In the meantime, with the number of frozen embryos reaching 1 million in the U.S., Daar predicts that litigation isn’t going away: “What is likely is that these disputes will continue to pile up in courts,” she says.