Not all litigation analytics products are created equal

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Litigation analytics products provide lawyers with critical insights into courts, judges, lawyers and litigants. It is valuable information to know that opposing counsel successfully motioned to dismiss 10 personal injury cases from a federal district court, four of which were decided by the presiding judge. But what if your research missed two motions to dismiss before the same judge that opposing counsel lost? Have you deprived a client of adequate representation?

When lawyers use litigation analytics, they expect software to deliver accurate and comprehensive results on a variety of litigation-related matters. A recent study conducted by law librarians, however, dashed those expectations.

At Law.com’s Legalweek Legaltech conference in New York City in February, Diana Koppang, director of research and competitive intelligence at Neal, Gerber & Eisenberg; and Jeremy Sullivan, manager of competitive intelligence and analytics at DLA Piper, presented findings from a 2019 study (updated in 2020) by 27 academic and law firm librarians comparing the answers of federal litigation analytics products to a set of real-world questions. The study defined litigation analytics as the marriage of docket analytics and semantic analytics.

Docket analytics allows researchers and attorneys to monitor and assess judicial profiles of prior decisions, motion times to resolution, win-loss rates, and other data that can help predict future outcomes to advise clients and determine case strategies. Semantic analytics derives from the words and phrases in judicial decisions. The analysis matches language with data point analytics, such as grant and dismissal rates.

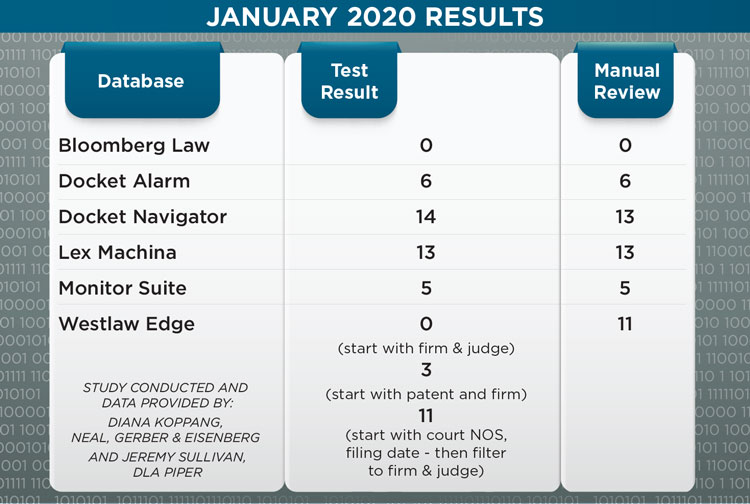

Test results of a query to determine the number of patent cases in which Irell & Manella appeared before U.S. District Judge Richard Andrews of the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware over a specified time period. Chart by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock.

The study focused on data from federal district courts reported by analytics platforms, not dockets platforms per se. The platforms evaluated were from Bloomberg Law, Fastcase (Docket Alarm’s Analytics Workbench), Docket Navigator, LexisNexis Legal & Professional (Lexis Context, Lex Machina) and Thomson Reuters (Monitor Suite and Westlaw Edge).

Real-world questions

“There were no pie-in-the-sky questions to try and break the platforms,” Koppang said at the conference. The testers brought real-world problems to the study from lawyers with clients in or contemplating litigation. For example: “How many motions to dismiss for failure to state a claim have been filed in [U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California] Judge Janis Sammartino’s court, and what percentage of those were granted?” But when the librarians tallied up the 16 questions and answers, it was clear that the platforms were not made equal.

For instance, when presented with the question “In how many [patent] cases has Irell & Manella appeared in front of Judge Richard Andrews in the District of Delaware?” and a date range beginning Jan. 1, 2007 (see results in chart above), no two vendors had the same answer.

Bloomberg Law found none, while Monitor Suite and Docket Alarm found five and six cases, respectively. Docket Navigator found 14 cases, Lex Machina found 13.

Westlaw Edge ultimately found 11, but testers had to start their search with the court, then filter on the firm and judge. When the research began with the firm and judge, Westlaw Edge found nothing. It found three cases when the search started with a patent and filtered on the firm name.

To verify the answers, the study presented the same queries in a docket search and performed a manual review.

Diana Koppang said “there were no pie-in-the-sky questions” in the study of litigation analytics platforms. Photo courtesy of Neal, Gerber & Eisenberg.

“The document is the source of truth,” adds Josh Becker, head of legal analytics for LexisNexis. “The system has to have the answer; the user has to understand how to extract the data from the system.”

For instance, all of the products used in the study draw federal litigation data from PACER, but no product has all the data, says Michael Sander, the founder of Docket Alarm and managing director of Fastcase. In general, “high-level PACER costs [would run] $2 billion to $3 billion to purchase all the records. Companies have to create a budget and download what they need to stay within it,” Sander says.

After the cost issue, PACER has data quality problems. When filing a civil complaint in federal district court, lawyers must complete and sign a civil cover sheet. The cover sheet is one page, containing necessary case information, such as the names and residences of plaintiffs and defendants, attorney names, the basis of jurisdiction and the nature of the suit–a single code.

The filer must identify one NOS code that best describes the case from more than 90 issue areas grouped in 13 categories. The selection of a NOS code is critical for court statistics, the allocation of resources to federal courts and the retrieval of case data, as Christina Boyd, an associate professor of political science at the University of Georgia, and David A. Hoffman, professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey School of Law, found in their 2017 paper, “The Use and Reliability of Federal Nature of Suit Codes.” Although some NOS selections, such as employment discrimination and intellectual property, do an excellent job of summarizing the legal content of a complaint, other codes do not, such as those for contract, real property and tort cases.

Michael Sander, founder of Docket Alarm and the managing director of Fastcase, says no single product has all the data. Photo by Alex Kotlik Photography.

Bloomberg Law, Docket Alarm,Lexis Context, Monitor Suite and Westlaw Edge claim coverage for all civil NOS codes. Coverage for Docket Navigator and Lex Machina, however, is limited by case types or NOS codes. If a civil case includes a claim that fits a vendor’s coverage area but the NOS code does not reflect it, the vendor might not export the case from PACER.

In addition to the NOS limitation, the study identified other PACER problems, including spelling errors or typos in attorney and firm names and incorrect attribution of attorneys to firms after lateral moves or acquisitions. New firms or attorneys may replace or substitute for original counsel or appear pro hac vice. Depending on the product, “law firms may not get counted for pro hac vice,” Sander says.

Platforms beg to differ

Platforms differ in many ways, including federal court coverage, update frequency, data normalization, quality control, search options and analytical features. All the products cover federal district courts; and most products, except for Lex Machina, include data on federal courts of appeal. Only Docket Alarm, Lexis Context and Monitor Suite cover federal bankruptcy courts.

How frequently vendors update PACER data can matter. “The time case data is pulled can change the accuracy of it,” Sullivan said during the Legaltech session. Most vendors update PACER daily, but Bloomberg Law and Docket Alarm can refresh case data on user demand or specification.

Vendors have various methods to implement authority control for things such as spelling and normalizing data on attorney, company, firm and judge names, among other things. All the vendors engage in some aspect of human review or quality control, whether they monitor the system for error correction or perform random audits to check for accuracy. But Docket Navigator uses legal editors to curate litigation data for patent, antitrust, copyright and trademark cases by hand, and it does not use algorithms to populate data fields.

Vendors apply different tagging and grouping schemes to PACER data, leading to differences in search options and other platform functions. All the platforms can search by attorney, firm and district court judge. But searching by bankruptcy, magistrate and other judges is spotty, as is searching by party name, be it a company or an individual.

Docket Alarm and Lex Machinahave the most comparison tools, including judges, jurisdictions, law firms and parties. All the products analyze motion outcomes for motions to dismiss and summary judgment, but only Bloomberg Law, Docket Alarm and Westlaw Edge analyze appeal outcomes. Note that analytics products are continually updating their software and analytics. Depending on the coverage, product innovation begets competition among the various platforms.

Takeaways

The study was not conceived as a contest and did not aim to find a winner.

From a high-level view, the law librarians’ study found that analytics research is different from case law research, and that vendors must provide transparency, training and guidance to use these systems properly. When combined with research from other platforms, such as company databases and docketing systems, analytics platforms generate the best results.

This article first appeared in the August-September 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline “Not So Predictable: Analytics products offer different results depending on data sources, quality and the types of analytics and reports they provide.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.