An admitted murderer seeks justice in the death of his daughter

Illustration by Stephen Webster.

But the reason Montour was in prison in the first place—serving another sentence of life without parole—was for the 1997 death of his 11-week-old daughter. It’s a crime he insists he didn’t commit. And his desire to be exonerated in her death has fueled a costly and complicated appellate battle over the validity of the original evidence against him, the effectiveness of representation leading to his first life sentence, and the implications his first imprisonment may have had for the second.

The facts of Montour’s case do not command easy sympathy; in complex criminal cases they seldom do. But his story raises serious questions about the frail standards of forensic science, about the broad and disparate range of death penalty representation, and about the nature and limits of justice itself.

On the one hand, had he not been convicted of killing his daughter, he wouldn’t have been in prison. And had he not been in prison, he wouldn’t have been in a position to murder a prison guard, whatever the reason: as a matter of simple survival, a surge of bipolar rage or an effort to gain a protective reputation for violence within prison walls.

On the other hand, perhaps it doesn’t matter. For at the end of the day, nothing will likely change for Montour. He will probably die in prison for the murder he admits he committed. But if cleared of his daughter’s death, Montour says he will do so knowing justice has been served.

The labyrinth of Montour’s case is best navigated by beginning with the prison killing—a brutally simple murder complicated by context.

It began with a dispute with other inmates over a single-bunk cell at Colorado’s Limon Correctional Facility. As in most prisons, single-bunk lockups are prized for their relative solitude and safety. The cells are assigned on the basis of seniority and behavior, and when an inmate was caught with a wire shank hidden in a tube of toothpaste, Montour was moved to his single-bunk cell as the next in line.

But in the closed ecosystem of prison, nothing is quite as it seems. The inmate claimed he had been framed, and suspicion turned to Montour as the person who most benefited. The inmate had been asked to hold a few items for Montour, ones that exceeded his allotted inventory. Among those items was a tube of toothpaste—the one in which the shank was found. An investigation revealed that guards had been alerted to the hidden weapon by an anonymous note. And when the inmate was cleared, he returned to Montour’s former cellblock, outspoken in the belief that Montour set him up.

Montour swore his innocence, maintaining that a recently paroled cellmate and jailhouse lover had actually executed the frame-up without his knowledge. Still, Montour says he began to fear for his life, and on the day before the murder he had been told that he would be killed if he returned to his cellblock.

Montour had been assigned to the prison kitchen. With the hope of being placed into protective custody—and to cement a reputation as a tough guy—Montour decided to kill a prison guard. The moment to do so came when the prison speaker system announced that Montour was to be returned to his cellblock. And when Eric Autobee went to fetch him, Montour pounced.

Montour hit the young guard with the ladle, and Autobee crumpled to the floor. When the guard began to move, Montour hit him again. With Autobee now laying still, Montour calmly placed the bloodied cast-iron ladle on a table, walked out of the kitchen and announced to the first guard he saw: “I just put Autobee down in the kitchen. Do you want to handcuff me now or later?” He walked toward a drink dispenser, poured himself a Mr. Pibb, took a seat at a nearby table and waited for Autobee’s body to be found.

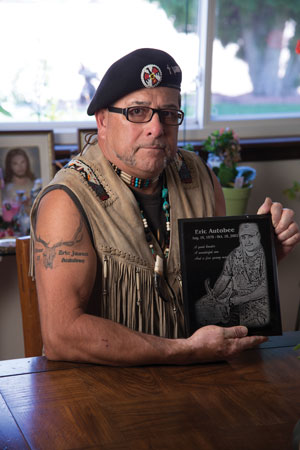

Bob Autobee, father of the murdered prison guard: “I don’t want to see anyone die in my son’s name.” Photograph by Paul Trantow.

For prosecutors, the calculated character of Montour’s crime required that he be tried for the death penalty. Having killed a small child and now a corrections officer, they argued that Montour was no longer a redeemable human being. Montour seemed to agree. He fired his lawyers and won the right to represent himself. He pleaded guilty and requested the death penalty. A Colorado trial judge concurred and sentenced him to death.

Montour seemed fated for execution until a Supreme Court decision reset his case. In Ring v. Arizona the court had ruled that only a jury could issue a death sentence. The decision sent Montour’s case back to the trial court. Though appeals are automatic in death penalty cases, Montour spent much of the next four years obstructing attempts to overturn his death sentence, supporting the prosecution’s contention that without the threat of execution, there would be no credible bar to killing a prison guard or a policeman or a judge.

“I have a potential of becoming a far worse and continuing threat to those around me and those in society in general,” Montour told the court at his sentencing hearing. “I haven’t been scared so far, so I wish the state to kill me. I don’t care.”

Montour has always maintained that the death of Taylor, his 11-week-old baby, was an accident. Montour was an unemployed insurance salesman and stay-at-home dad in March 1997, when the child suffered her fatal fall. Montour says he was sitting in a rocking chair, feeding her, when he reached for a burp rag on the windowsill and dropped her. She fell backward, perhaps hitting her head on the chair before falling to the carpeted floor. The child cried briefly but soon stopped. It wasn’t until his wife, Terrie, came home from work and noticed Taylor’s breathing seemed shallow that the couple became concerned. They called her doctor and made an appointment to bring her in later that night. But Taylor suddenly stopped breathing, so they called 911. A few hours later, the girl was dead.

At the hospital, however, her doctors were confronted with a broad range of serious injuries—a skull fracture, a broken leg, several broken ribs in various stages of healing, as well as brain swelling and bleeding around the brain and in the eyes—and immediately suspected that they were looking at a battered and abused child. Dr. David Bowerman, the El Paso County coroner at the time, ruled Taylor’s death a homicide due to blunt head trauma consistent with shaken baby syndrome. Several emergency room doctors who had treated Taylor in the hospital ER supported Bowerman’s contention that the injuries Taylor suffered could not have been caused by the fall Montour had described.

At Montour’s 1998 trial, Bowerman likened the injuries to ones caused by a motor vehicle accident or a 10-story fall. He said he had considered Montour’s version of events but didn’t believe it. “This is a battered child with multiple repetitive injuries of intentional type,” he testified.

At that trial, other witnesses painted Montour as something less than sympathetic. Several said he seemed not to grieve properly for his dead baby. Two former cellmates were brought before the jury to testify that he had confessed to them while he awaited trial.

Perhaps most damaging, however, was the testimony of a friend and former co-worker of Montour’s who had visited Montour at his home on the day Taylor died. The witness, a married man who reluctantly admitted that he and Montour had a secret sexual relationship, said that he and Montour drank at least five shots each of Seagram’s and 7-Up that day. At 2 p.m., when the witness left to pick up his wife at work, Taylor seemed fine, the witness said. But he added that a few days earlier Montour had told him what he had regarded as a joke at the time: that he wished his wife, Terrie, would, “just go away, disappear.”

When Montour testified in his own defense, he was a poor advocate for himself. He admitted he hadn’t told his wife that he had dropped Taylor until it was too late to save her life, or that his friend visited the house and the two had been drinking. He denied a sexual relationship with his friend and, rather lamely, insisted that he may have made Taylor’s fall worse by overcompensating when he tried to catch her.

It didn’t take long for the jury to find Montour guilty on both counts. He was sentenced to life in prison without possible parole on the murder charge, plus 48 years for child abuse. He was sent to Colorado’s Limon Correctional Facility, a “close-security” prison with a reputation for corruption and gang violence.

THE DEFENSE TEAM From left: Hollis Whitson, Kathy McGuire, Kathryn Stimson and David Lane revisited Montour’s claim of innocence in the death of his daughter and found the forensic evidence against him to be questionable. For one thing, the science of shaken baby syndrome had changed dramatically since his first trial. Photograph by Paul Trantow.

The day after his conviction, Montour began complaining about his deteriorating mental state. A day after that, he received the first in a long series of diagnoses for bipolar disorder type 1. Known in some medical circles as “raging bipolar,” type 1 bipolar disorder is often characterized by hallucinations, delusions and thoughts of suicide or homicide. It’s also a condition that Montour’s lawyers say is exacerbated by stress.

If properly medicated, the symptoms may not be debilitating; without medication, the symptoms return. But many sufferers find that the medication muddles their minds and slows their reflexes—two very debilitating attributes in a prison environment. And over the four years that elapsed before he murdered Autobee, Montour was reluctant to medicate himself with any of the dozen or so prescribed medications unless the symptoms grew acute.

In 2007, after years of wrangling, the Colorado Supreme Court remanded Montour’s case back to the trial court, ordering that his sentence in the Autobee case be determined by a jury.

Montour’s new lawyers were faced with a dilemma. Though his sentence had been overturned, his guilty plea hadn’t. He still faced the death penalty—this time before a jury. And although they believed him to be psychotic at the time of the Autobee incident, Montour’s behavior was so calculated and so egregious that the death penalty seemed like more than a possibility.

But any death sentence would hinge on his conviction for Taylor’s murder. So the defense team, led by David Lane, began to revisit Montour’s claim of innocence in the case. What they discovered as they reviewed the record convinced them that Montour’s claim had merit. Much of the forensic evidence against him became questionable when examined more closely, making more credible Montour’s claim that Taylor’s death was an accident.

First, the science of shaken baby syndrome had changed dramatically since 1998, when Montour was first tried. Much of what the jury had been told about the diagnosis had been discredited by research. At the time it was still widely believed, for instance, that a fall from a short distance could not cause the kind of head injuries Taylor suffered, and that an infant with a serious head injury could not experience a period of lucidity before the onset of symptoms. But new scientific research done since then had shown that short-distance falls can cause fatal head injuries in infants, and that infants who suffer traumatic head injuries can be lucid for hours or even days before becoming symptomatic.

The jury had also never been told that Taylor, who was born two months premature, spent the first month of her life in the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit, where she was diagnosed with a serious blood-clotting disorder called disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, which can occur when a person suffers a trauma such as a head injury, the defense lawyers contended. DIC prevents the blood from clotting and causes spontaneous bleeding and easy bruising, which could account for some of the injuries emergency room doctors saw as telltale signs of abuse.

From X-rays not seen by the jury, it was discovered that Taylor may have suffered from rickets, a bone disease that could account for the fractures doctors had uncovered in their efforts to save her. Even more telling was the muddled role of first responders, who may have contributed to the child’s injuries in their efforts to revive her.

The operator who fielded the 911 call apparently misunderstood Taylor’s age, giving Montour CPR instructions more appropriate for a 3-year-old than a fragile child of 3 months, says defense lawyer Kathryn Stimson. Emergency tapes showed that she instructed Montour to perform CPR using the heel of his hand to press against her ribs, instead of his fingers. Moreover, it was discovered that emergency responders, having tried and failed to insert an IV line, then tried to insert an intra-osseous line into the bone marrow of her leg, which the defense contended could account for the fracture of her right femur that prosecution experts had testified was indicative of abuse. The emergency response team had also intubated Taylor incorrectly, placing a breathing tube into her stomach instead of her lungs, which may have made a bad situation much worse.

As for the jailhouse snitches to whom Montour had confessed, at least one recanted during a defense team interview, saying there was “a good possibility” he had been lying in his testimony at the trial. The other is dead.

So compelling were the discrepancies in medical evidence that Leon Kelly, the El Paso County deputy coroner, has reclassified Taylor Montour’s death from “homicide” to “undetermined.”

“Given the valid possibility of metabolic bone disease resulting in fragile bones and a reported mechanism of a multi-impact, low-distance fall in the presence of apparent multidirectional impact in an infant with rapidly progressive, clinically documented DIC, it is beyond the abilities of autopsy science to determine beyond reasonable medical certainty whether the death of Taylor Montour was due to accidental or nonaccidental (abuse) trauma,” he said in a report explaining the decision.

But what of Montour’s lawyers? In a case that depended almost entirely on medical evidence, Montour’s attorneys at trial never consulted—much less called to testify—a single expert witness. They never challenged the two jailhouse snitches, tried to negotiate a plea bargain or bothered to meet with the public defenders that had first been assigned to Montour’s case.

During the trial Montour’s lead trial lawyer, Fredrick M. Callaway, repeatedly and mistakenly referred to him by the name of another client, telling the jury during his closing argument that Montour was either “lying about what had happened, or someone else killed that child.”

Callaway, who is back in good standing with the Colorado Office of Attorney Registration after two earlier run-ins with lawyer disciplinary authorities, didn’t return calls for comment. Records show he was suspended twice for six months each: first in 2008 for failing to cooperate with his own investigators and inattention to client files; and again in 2009 for filing a complaint on behalf of a client and then failing to serve it, and for failing to pay the client’s husband for work he performed at Callaway’s request. He was reinstated last March.

In a 2011 affidavit, Callaway described himself as ineffective in his representation of Montour in a number of ways. He said that he was under enormous financial and marital stress at the time, and that the stress of representing Montour and his marital problems had exacerbated his chronic clinical depression. He also said he had spent much of the previous year trying another murder case for a client named Edwards, the name he kept using instead of Montour’s during the trial. Moreover, he said he didn’t much like Montour, didn’t “connect” with him and didn’t believe his story that Taylor’s death had been an accident.

In April 2013, after years of contention, a Colorado judge allowed Montour to withdraw his guilty plea, citing his history of mental illness. The prosecution remained determined to try Montour and to ask for the death penalty, but the landscape of the case had changed dramatically. Montour’s defense had changed to an insanity defense, and it was clear that Montour’s lawyers were determined to put his first conviction on trial.

But Dr. Bowerman, who had conducted Taylor’s autopsy, was severely ill and near death. Several key witnesses, including one of Montour’s lawyers, had died. The prosecution had been unable to preserve much of the evidence from the first trial, and key exhibits were destroyed. Worse, the change in Taylor’s death certificate meant that there was no longer any certainty that a homicide had been committed. And worse yet, Autobee’s parents began a vocal campaign against the prosecution’s decision to seek the death penalty, arguing that it seemed inappropriate for Montour’s state of mind.

“I don’t want to see anyone die in my son’s name,” says Bob Autobee, the dead guard’s father. Still, the prosecution argued that nothing presented by the defense in the way of evidence or experts discounted the earlier determination that Taylor had died as the victim of long-term physical abuse. Moreover, they argued that Montour, far from being insane or incapacitated, had carefully calculated a strategy to get away with “the perfect crime.”

Presenting the court with a lengthy compendium of Montour’s prison letters, poetry and testimony, they argued that Montour had wanted to get away with murder, by ending up with the same sentence he had received for Taylor’s death—life without parole.

“I committed murder at Limon Correctional Facility to show them that I can get away with murder,” Montour wrote in one letter. “But now, for the sake of my soul, I need to be held accountable.”

Montour’s trial began the first week of March 2014. Two days later, it ended when Montour pleaded guilty to the Autobee killing in exchange for life without parole. It was over.

“I had to get as much justice out of this situation as I could,” said George Brauchler, the district attorney over-seeing the prosecution.

After sentencing, Montour was transferred to Wisconsin so as not to return to the same prison where he had killed a guard.

But it’s not over. Before a conflict of interest emerged to force Lane and Stimson from the case, they sought a new trial for Taylor’s death. Like Montour, they want his new lawyers to help clear the earlier conviction; but prosecutors are resisting, saying it’s too late. Still, Stimson calls the case “a tragedy the likes of which you cannot imagine.” She also says Montour “wants the record to reflect that he never should have been in prison in the first place.” Lane says that allowing the conviction to stand would be “the most egregious miscarriage of justice” he’s seen in his 34 years of practice.

The irony of the situation has never been lost on Montour. In one of the letters cited by prosecutors as evidence of Montour’s calculation, he wrote to his mother in 2002 describing the paradox.

“It bogels [sic] my mind to find out that my defense council [sic] tells me that I should never of been convicted of Taylor’s death. I commit a real murder just to find out I should have been a free man.”

Whether or not that is true, former El Paso County District Attorney John Newsome, the lead prosecutor at Montour’s 1998 trial, says he favors reopening the case. The whole theory, based on the testimony of the state’s medical experts, was that Montour had beaten his daughter over a period of several weeks and, on the day she died, had shaken her and slammed her head into a hard surface.

“If there is evidence that now indicates this was not a homicide, and the coroner now says that it was not, then the entire thing needs to be reopened and re-examined,” says Newsome, now a defense lawyer in Colorado Springs. “I’m of the opinion that it’s never too late for justice.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “An Innocent Killer? An admitted murderer seeks justice in the death of his daughter.”