When researchers began the painstaking work of identifying Indigenous children who died at the Genoa U.S. Indian Industrial School in Nebraska, they kept making chilling discoveries.

Although old newspaper clippings, student newsletters and death records revealed students had died of flu, complications from tuberculosis, measles, polio and pneumonia, other deaths were suspicious. Two children died in accidental shootings, one child was hit by a freight train and another died after a fistfight. One newspaper clipping says a 12-year-old boy died from “eating too much cheap candy.”

The true fates of these children may never be known. But Judi M. gaiashkibos, the executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs, who is leading a search to find a cemetery where children were buried, believes some were trying to escape or took their own lives.

"Will we ever get full justice? No, we never will." —Judi M. gaiashkibos

“I was disgusted, saddened,” says gaiashkibos, describing how she felt when she heard about what the researchers had found. “I can’t say that I was shocked. I wish I could say that. But when I think how we’ve been treated for hundreds of years in America, it doesn’t come as a big surprise.”

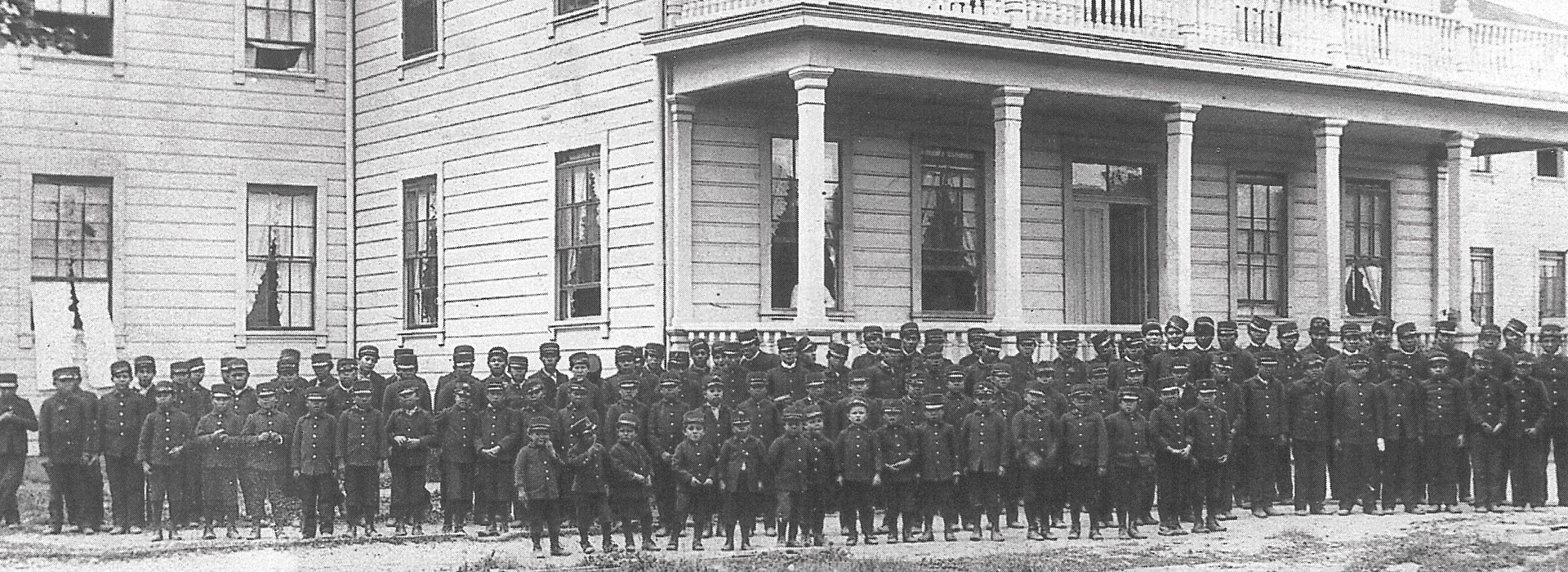

Thousands of Indigenous children attended the school in the small city of Genoa, about 100 miles west of Omaha, between 1884 and 1934. Some of those children never saw their families again. Gaiashkibos and researchers at the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project have confirmed that at least 86 children died.

Genoa was one school among hundreds. The schools were modeled on the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, whose superintendent, Capt. Richard Pratt, said the school’s purpose was to “kill the Indian in him and save the man.” The schools, run by the federal government and churches for more than a century, were meant to indoctrinate hundreds of thousands of American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children, reprogramming them to act and think like white Christians. The now-shuttered school buildings are monuments to a legacy of forced assimilation that stripped the children of their names, language, culture and religion. Although the schools haunt generation after generation of Native people, many Americans know little about them.

But now some Native Americans hope there can be a national reckoning and a path to justice for survivors and descendants. In June 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, an enrolled member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe and the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, announced a probe to uncover the locations of burial sites at or near the grounds of these schools and account for human rights abuses. The discovery the previous month of 215 unmarked graves in Canada by Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc First Nation at the Kamloops Indian Residential School precipitated the investigation.

Last year, Brad Regehr, a member of the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation in Saskatchewan and partner at Maurice Law in Winnipeg, Manitoba, ended his one-year term as Canadian Bar Association president. He is the first Indigenous lawyer to hold the office, and he spoke at the ABA Annual Meeting in August as the House of Delegates passed a resolution in support of the U.S. investigation and pending truth and reconciliation bills in the House and Senate.

“That ugly truth that was in the history of Canada, that’s an ugly truth in the history of the United States,” says Regehr, whose grandfather was a survivor of the residential schools. “It’s going to take a lot of time to reconcile and repair the damage that has been done.”

But there’s uncertainty about how the U.S. government and the courts will meet demands for justice.

"It's going to take a lot of time to reconcile and repair the damage that has been done." —Brad Regehr

“Indigenous people collectively have to decide what reconciliation looks like,” says Mary Smith, who is a member of the Cherokee Nation and is believed to be the American Bar Association’s first female Native American president-elect nominee. “You could envision some legal remedy, but it’s very early in the process.”

Smith notes that the United States is far behind Canada, which launched its Truth and Reconciliation Commission in June 2008. The commission was created as part of a 2006 agreement settling class action lawsuits filed by thousands of former students. In 2021, it was reported that nearly 28,000 survivors were paid more than $3.2 billion in compensation.

In addition, $1.9 billion was allocated for former students for loss of language, culture and family life, and for education. The settlement agreement included an apology from the government and churches, and funding for community development and healing.

The head of the United States’ National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, Deborah Parker, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribes, says her group has been sharing information and records with researchers from the Department of the Interior, and in May, the department published the first volume of its investigative report. The department found that from 1819 until 1969, there were 408 Indian boarding schools. Investigators identified burial sites at 53 different schools and said more than 500 children had died. It expects the number of identified burial sites and recorded deaths to increase as the investigation continues.

In the meantime, gaiashkibos, an enrolled member of the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, has responsibility for what happens to human remains under state law if the cemetery in Genoa is found. She says the search is fraught with fear about what they might find.

“Are they going to be in a mass grave? Are they going to be in individual graves? There’s just a lot of things we don’t know,” she says.

If she does find the cemetery, gaiashkibos says she’s going to have to make some hard choices. It could mean returning the human remains to their tribes or creating a memorial at the burial site. She says as many as 44 different tribes may have had children at the school. The process of notifying them about the identities of the children revealed in records already has begun.

Parker says what’s sometimes overlooked about the burial sites is that many Native Americans have a spiritual connection with their ancestors, and descendants and survivors are still haunted by dreams and visions about the children.

“The messages that many of us are receiving are from the children who are still lost and are asking to be found,” Parker says. “It’s so important for us, historically and culturally, to find these children and bring them home.”

Like many other Native families and tribes, gaiashkibos has a personal connection to the Genoa school. In the 1920s, her mother, Eleanor Josephine Knudsen, and two aunts, Linda and Bernice, were taken from their parents to go there. At that time, the government would threaten to cut off food rations if parents refused to hand over their children, she says.

The school staff separated Knudsen from her sisters so they couldn’t speak to each other.

“To kill the Indian, you kill the language and kill the culture,” gaiashkibos says, adding that in boarding schools, harsh punishment—including beatings—was dished out to children who dared to speak in their native tongue.

Education at the school focused in the mornings on the three R’s—reading, writing and arithmetic—and learning a trade in the afternoon.

The school used the children as free labor both inside and outside of the school. Knudsen spent her afternoons cooking, cleaning and sewing. Many children didn’t go home in the summer but were shipped out to work for local families and businesses, gaiashkibos says.

Most of the buildings on the 640-acre campus in Genoa were bulldozed years ago. A single red brick schoolhouse remains. When gaiashkibos was little, her mother didn’t talk much about school life. When she did, gaiashkibos felt pangs of sadness and ambivalence.

Children at the boarding schools were used to fight the “last war of the United States government against the Indian people,” she says, in a bid to annihilate their identity and culture and steal their land.

“As in war, some people die and some don’t. Thank God my aunties and mother survived. But a lot of children didn’t,” gaiashkibos adds.

Although gaiashkibos’ search for the Genoa cemetery has been in progress since October, other schools in the U.S. already have repatriated the remains of children back to tribal lands. In summer 2021, nine children who died at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania were transferred to the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and buried at its Veterans Cemetery or in family cemetery plots.

Carlisle opened in 1879 and closed in 1918. At least 186 children perished there. School staff cut their long hair into bowl cuts, gave them English names, forced them to wear government-issued uniforms and made them march like soldiers. In this way, it was a militarized prototype for schools across the country.

The ABA’s report for an August House of Delegates resolution in support of the U.S. investigation into boarding schools notes appalling conditions. Although some former students have said the boarding school experience was positive, the report says the system was rife with neglect and sexual and physical abuse. Campuses were petri dishes for disease. In some cases, children were forced to build coffins for other students who died in the schools, said Mark I. Schickman, a delegate with the Civil Rights and Social Justice Section, as he introduced the resolution.

Indigenous historian and anthropologist K. Tsianina Lomawaima’s father, Curtis Carr, attended the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School in Oklahoma. Like similarly named “industrial” schools, it focused on teaching trades.

Kids at the school were divided into gangs and pitted against each other. More than once, Carr was forced to run the “beltline,” Lomawaima says, weaving between two rows of boys who rained blows down on him with belts.

“My dad would say if there was some kid from another gang who had it out for you, he might hit you with a buckle instead of the strap,” says Lomawaima, who is of Muscogee descent and wrote a book, They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School, based on interviews with her father and other students.

Lomawaima’s father eventually escaped from the school.

Diné/Navajo historian Jennifer Nez Denetdale’s parents met at the Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nevada. Denetdale says her parents, Frank and Rose, faced harsh discipline and punishment.

“They see how children are treated and think that all children should be treated like that,” Denetdale says, referring to her parents’ experience.

Her father was hardworking, dedicated and devoted, but “for the longest time, my father had a hard time showing any of us any kind of emotion you could call love,” she says. She recalls her mother cleaning the family home with Lysol, Pine-Sol and Clorox—a routine she picked up from her boarding school years. During bath time, her mom washed Denetdale and her sisters down with laundry soap.

“It would be peeling off the top layer of our skin,” Denetdale says.

“Look, dirt,” her mother would say.

“It’s our brown skin that’s peeling off. It’s from the boarding school that dark skin equals pollution, and dark-skinned equals dirty,” Denetdale says.

When Denetdale got out of the bath, her mother would rub the children down with Bengay cream to relieve their pain. “I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,” she says.

A truth and reconciliation commission in the U.S. is likely to mirror Canada’s reckoning with its own human rights abuses. But although Canada’s residential school system was modeled after U.S. schools, it is a decade and a half into a process that was sparked by a massive wave of litigation.

There are other differences. In its report, the Interior Department said about 90 schools might still be open. But not all of them operate with federal support or board children. According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, the boarding school era ran from 1860 until the 1970s, when the government relinquished control of the schools to the tribes. That was after Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Educational Act of 1975. In Canada, the last residential school closed in 1996.

In the U.S., survivors have faced barriers in court. For example, in the early 2000s, former students in South Dakota sued the federal government alleging rampant sexual and physical abuse by priests and nuns at Catholic-run schools operated during the boarding school era. (The government funded those schools.) And in 2011, a South Dakota judge threw out 18 lawsuits filed by Native American plaintiffs after the state legislature amended the statute of limitations to prevent anyone over the age of 40 from suing for child sexual abuse—a move critics have said unconstitutionally targeted Native Americans to prevent them from filing lawsuits.

In 2006, Andrea A. Curcio, a law professor at the Georgia State University College of Law, published a paper about legal remedies available to victims of the boarding schools. She wrote that what happened at the schools violated not only international human rights law but also treaties between the government and tribes. Still, survivors face a host of obstacles because of statutes of limitations and governments’ immunity defenses.

Curcio says there is no simple solution to meeting demands for justice, although Native American people could pursue reparations. Congress could pass a law eliminating the government’s statute of limitations defense for civil claims in these cases and also waive sovereign immunity, but Curcio says this is unlikely.

Parker says there also is an inherent distrust in the justice system among many Native Americans. Much like they were alienated from their families and tribal lands while in boarding schools, they have a disconnect with the nation’s courts.

“That distrust comes from generations of legal disparities that Native people have witnessed within the court systems and policing. How are we to seek justice in a court system that doesn’t see us?” Parker says.

Added to that, the Indian Child Welfare Act, a federal law governing the removal and out-of-home placement of Native American children, faces a constitutional challenge. The law was passed in 1978 to address the legacy of the boarding schools, including a finding that 80% of Indigenous families had at least one child in foster care. It was enacted to help prevent children from being taken to off-reservation schools or placed in the foster care system.

In February, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear four cases, consolidated under the name Haaland v. Brackeen, involving challenges to the law, which gives placement preference to Native American families in adoption cases involving Native children. Plaintiffs argue that the law violates the equal protection clause.

Many of the Indigenous people the ABA Journal spoke with are encouraged that Haaland, whose grandparents went to the St. Catherine’s Industrial Indian School in Santa Fe, New Mexico, is leading the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. But federal investigators and Indigenous groups face an immense task. This is mirrored in the effort to find the U.S. Industrial Indian School’s cemetery in Genoa.

Efforts to unravel the mystery of how students died have been ongoing for more than a year. The Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project has sent researchers as far as Colorado, Kansas City, Oklahoma and Chicago to gather records. Gaiashkibos says this is because there is no central depository of school records. Sometimes tribes have kept death records. But they didn’t always report them to the federal government, Genoa or Carlisle. This means records were dispersed widely, including at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln historian Margaret D. Jacobs, who also is part of gaiashkibos’ research team, says they relied on notices in the local newspaper, the Genoa Times, and archives of the newsletter that students published at the school. The newsletter was once called the Pipe of Peace, then the Indian News.

"I'm doing this because I have to do it. It's more important to find those children than risk upsetting someone." —Judi M. gaiashkibos

The way the local newspaper reported on deaths shows a callous indifference, Jacobs says. The notices were not obituaries, but rather summaries. They were inserted, almost as an afterthought, between advertisements and articles.

“The death notices of the children, as you might imagine, are so different because these are their friends and their peers,” says Jacobs, explaining what researchers found in the student newsletters. “This is terrifying to the children, and so their death notices are more detailed. They’ll tell you what the child likes to do. They’ll tell you about sports that they played.”

In the course of gaiashkibos’ search for the Genoa cemetery, the trail led her to land owned by a farmer. He was cooperative, but gaiashkibos made clear she would use whatever authority she has to find the children, including getting a court order.

“I would be willing to do that to find those children’s graves. I’m not doing it in a hostile way. I’m doing this because I have to do it. It’s more important to find those children than risk upsetting someone,” she says.

Last year, then-state archaeologist Rob Bozell worked with a contractor to collect data and scan 12 potential gravesites with ground-penetrating radar, but an analysis of data it gathered did not reveal the cemetery’s location.

Canadian lawyer and law professor Kathleen Elizabeth Mahoney says reaching a settlement in Canada meant putting demands for justice into the hands of Indigenous people and respecting their legal principles, which are often based on the community rather than individuals.

Mahoney, who was the chief negotiator for the Assembly of First Nations as it settled what happened in the residential schools, says there were many barriers to justice. Witnesses were dead, memories had faded.

In Canada, as in the United States, there are often statues of limitations on physical abuse, governments have strong immunity defenses, and victims face the prospect of having to relive their trauma in court.

"They wanted to tell their stories in a safe place where they would be believed." —Kathleen Elizabeth Mahoney

In her 2018 paper “The Untold Story: How Indigenous Legal Principles Informed the Largest Settlement in Canadian Legal History,” Mahoney wrote that class action lawyers for the former students were steeped in the “deeply embedded assumption that colonial law was and is superior to the preexisting Indigenous legal traditions.”

Because of that, the lawyers failed to understand that survivors wanted not just compensation but truth and reconciliation.

“They wanted to tell their stories in a safe place where they would be believed. They wanted to live a life where they weren’t plagued by their past histories and their hatred and bitterness. They wanted to heal. They wanted to be treated with respect,” Mahoney says.

In addition, Indigenous people wanted funding to address education, healing and the vagaries of a residential school system that stripped generations of their language and culture and deprived them of a stable family life.

In 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission called for 94 causes of action, including recommendations on how the justice system should handle claims.

Exiling children from their parents and their tribal land and language in the United States had ripple effects that still are felt by Indigenous people today, according to Trigger Points, a 2019 report by the Native American Rights Fund. It suggests descendants of students who were forced to go to the schools are less likely to speak an Indigenous language, and the trauma inflicted from the boarding school experience can make survivors and their descendants more likely to slip into drug and alcohol abuse. To this day, a disproportionate number of Native children end up in foster care.

“Trauma in Native American communities from the reservation system still exists,” Smith says. “Poverty still exists. Everyone is experiencing an opioid crisis, and it’s particularly acute in Indian Country.”

The power of the Department of the Interior is limited, which is why Indigenous groups and advocates want Congress to move forward with the two bills in the House and Senate. Last year, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., reintroduced the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act. If the bill passes, it could provide a culturally sensitive forum for victims to talk about the impact of the human rights violations at the schools.

“We must establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies to carry on the Interior’s work and investigate this moral stain that led to the forced assimilation of Native children,” Warren said in an email.

Rep. Sharice Davids, D-Kan., a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation, reintroduced the bill in the House with longtime Rep. Tom Cole, R-Okla., an enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation.

“I do think it’s possible for us to find healing. For us to get there, it has to be a big effort by a lot of people, and the federal government has to be part of that,” Davids says.

Lomawaima notes that interest in the boarding schools has “waxed and waned” over the years. She is worried the same could happen again.

“There’s been a very intentional erasure of history in this country when it comes to Native people. That’s at the root of my skepticism of how long the interest will last or how deep it will go,” Lomawaima says.

Gaiashkibos doubts that compensation or reparations could ever make up for the land stolen, the treaties violated or lives lost at the schools.

“Will we ever get full justice? No, we never will,” gaiashkibos says.

Gaiashkibos was 19 when her mother died at age 58. She says the school’s attempts to erase her mother’s Indian culture and traditions failed. After she left the school, her mother eventually was elected to the tribal council for the Ponca tribe.

Smith says what happened at the schools shows just how resilient Indigenous people are.

“Despite everything that has happened to them—despite things that still happen to them—we are still here,” Smith says.