Aftershocks: Navigating the morass of state abortion laws post-Roe

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford / ABA Journal

Loretta J. Ross recalls when she was 14 years old and being babysat by a family member. But instead of looking out for his young charge, the 27-year-old relative plied the teenager with alcohol and had sex with her. As a result, Ross became pregnant.

Ross, who was in 10th grade, grew up in San Antonio with her parents and seven siblings. She describes them as being “uber-Christians” who did not believe in abortion, which was illegal then in pre-Roe Texas. A decision was made: Loretta would give birth and put the baby up for adoption.

“The day after I delivered my son, the child was supposed to be whisked away and handed over to the adoption agency,” says Ross, who is now an associate professor of the study of women and gender at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. “I had actually signed the preliminary papers to make that happen. But the day after he was born, whether it was a mistake or done intentionally, the nurses brought my son to me. And I looked at him, and all I could say was, ‘Oh, my God! He’s got my face!’ And then the mother bonding thing happened. I can’t explain it. I didn’t plan on it. But I couldn’t go through with the adoption.”

Ross had been on track to attend Radcliffe College on a scholarship, which she lost after she became a teen mom. Little did she know that parenthood would be the first of many battles that she would end up fighting as a teenage mother. Shortly after giving birth in 1969, she and her parents threatened to sue her school district when administrators refused to readmit her after her pregnancy.

“They told me that they felt that other girls might get pregnant,” she recalls. “I said to myself, ‘Wait a minute. I don’t know how all of this works, but I am sure I can’t get anyone pregnant.’”

Lasting repercussions

On June 24, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled “the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion” and overturned Roe v. Wade. Allowing individual states to determine the legality of abortion has resulted in a confounding landscape of laws, bans and restrictions, creating a maze of hurdles for those seeking medical assistance and doctors performing the procedure—as well as a backlog for clinics in states without bans.

Not long after the Supreme Court’s conservative majority in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruled 6-3 in favor of restricting abortion, the world watched a horrifying case unfold involving a 10-year-old girl from Ohio who was raped and became pregnant. She had to travel to Indiana to have an abortion since Ohio’s “heartbeat bill,” which bans abortion after six weeks, was in effect. Already on the books since 2019 but blocked in federal court, it became effective after the court granted Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost’s motion to dissolve the injunction that had impeded it. In September, a judge temporarily blocked the Ohio ban pending a state constitutional challenge.

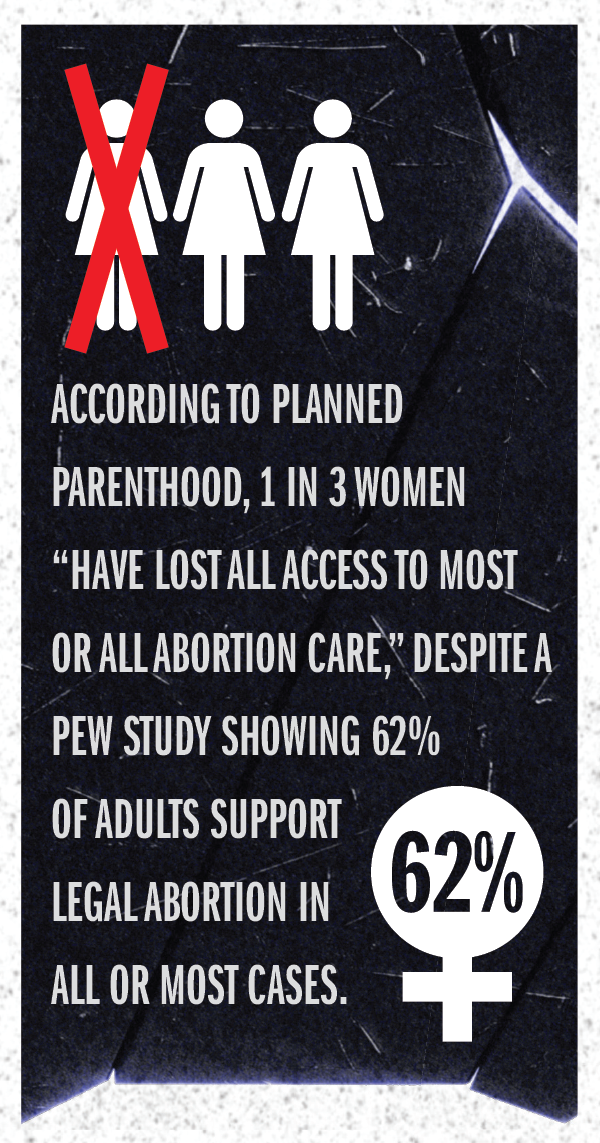

The Washington Post reports that since the landmark case was overturned, more than two dozen states have banned or mostly banned abortion. Seven states have bans that have been blocked in the courts. According to Planned Parenthood, 1 in 3 women—not to mention transgender, nonbinary and nonconforming people who can become pregnant—“have lost all access to most or all abortion care.”

“In states with bans, access to abortion was already very limited,” says Mary Ziegler, a legal historian and professor at the University of California at Davis School of Law. “But an absolute ban, as we see in this growing list of states, makes a difference—first, by eliminating what had been limited access very early in pregnancy; and second, by dramatically increasing the penalties faced for abortion (in Texas, for example, someone who performs an abortion can face up to life in prison).”

Texas is listed among the states with the “most restrictive” abortion laws, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which supports reproductive rights. The state has multiple abortion bans in place, including a trigger law that “creates harsh criminal penalties for providers and doctors, without exception for rape or incest,” according to information provided by the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas. Abortion-related telehealth has been banned, so a medication abortion, which uses prescription drugs to end a pregnancy during earlier stages, requires an in-person visit. And abortions can be performed only if a patient has “a life-threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from a pregnancy.”

A 2020 survey showed that medication abortions accounted for more than half (54%) of all pregnancy terminations in the U.S. Guttmacher also reported in 2020 that there were 930,160 abortions nationwide, up from 916,460 in 2019. Only a small fraction of abortions are performed because of rape or incest.

Ziegler, author of Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present, also points out that the Dobbs decision was not an indication that the country’s views on reproductive rights have shifted.

“Instead, there have been changes in how the Republican Party has handled the abortion issue—catering to primary voters with the most passionate views rather than to the largest number of voters—and in how the Supreme Court operates, especially in areas where precedent is established and public opinion is clear,” Ziegler says. “Dobbs was a product of changes to our political system and our democracy, not our basic ideas about abortion.”

According to a July 2022 Pew Research Center survey taken after the Supreme Court overturned Roe, 62% of adults support legal abortion in all or most cases; 36% said it should be illegal in all or most circumstances. The public’s views on the issue changed little from a survey taken before the Dobbs decision was leaked to the press.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports nearly 3 million women in the U.S. have experienced a rape-related pregnancy. Still, abortion opponents are making it increasingly difficult for women who are victimized by rape or incest and who may become pregnant as a result to access the medical care they need, when they need it.

In the case of the Ohio victim who had to travel to Indiana, a 27-year-old man was arrested and charged. That is not the usual outcome for most rape cases, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, also known as RAINN. The agency reports that of every 1,000 sexual assaults, only 310 will be reported to police and just 50 will lead to arrest; 28 cases will lead to conviction; and 25 rape offenders will be incarcerated. Most perpetrators—975 of the 1,000—in all likelihood will not face charges. Some abortion laws require rape victims to complete a police report.

“It was very complicated to try and raise my son and try not to take my dysfunction out on him,” says Loretta J. Ross. “As my son got older, we talked about this. I had to apologize to him because I was never able to give him unconditional love.” (Photo by Heath Robbins / ABA Journal)

“It was very complicated to try and raise my son and try not to take my dysfunction out on him,” says Loretta J. Ross. “As my son got older, we talked about this. I had to apologize to him because I was never able to give him unconditional love.” (Photo by Heath Robbins / ABA Journal)

Ross says the relative who raped her left the country to evade the wrath of her father. In the early 1970s, she was in her first year at Howard University when she became pregnant again by her boyfriend, who also was in school. They both decided to end the pregnancy, and they were able to do so in Washington, D.C., where abortion was legal. Ross graduated from Agnes Scott College and later became the national coordinator of the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Collective. She also co-authored Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique.

“I’m still that pissed off 14-year-old girl who couldn’t decide on if and when I had sex, if and when I had a baby,” Ross says. “The lack of self-determination still animates me. I remember how hard it was to become a teen parent.”

Dobbs, meet the Janes

That early fight for reproductive rights was the subject of The Janes, a documentary shown at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival that premiered on HBO in June. From 1969 to 1973, the Jane Collective, an underground network of women, provided thousands of illegal abortions in Chicago in defiance of the many dangers they faced—such as being arrested or running afoul of the mob, which profited from performing illegal abortions. A film about Chicago’s abortion operation, Call Jane, was released in theaters in October.

Elizabeth Banks stars as a suburban housewife seeking an abortion in Call Jane, which dramatizes the real-life Chicago underground network that operated during the 1960s and ’70s. (Photo by Roadside Attractions.)

Elizabeth Banks stars as a suburban housewife seeking an abortion in Call Jane, which dramatizes the real-life Chicago underground network that operated during the 1960s and ’70s. (Photo by Roadside Attractions.) Rabbi Tamar Manasseh is a Chicago activist who founded the nonprofit group Mothers/Men Against Senseless Killings in 2015, after a mother was murdered on a street corner. In 2021, she became the first Black woman to be ordained to the rabbinate at Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation.

In much the same way she felt it necessary to interrupt the violence perpetrated on Chicago’s residents, when the Dobbs ruling came down, Manasseh was once again spurred into action. This time, she partnered with the Chicago Abortion Fund to create a new initiative called We Are Jane, based on the Jane Collective.

“Roe being overturned, it’s terrifying. As a Black woman in this country, it’s terrifying,” Manasseh says. “Every right Black people have in this country has been given to us with the stroke of a pen. … Once you start taking things back, what’s next? For me, it’s such a slippery slope.”

Religious freedom was the basis of a lawsuit filed in June by a synagogue in Boynton Beach, Florida, challenging a state law that bans abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Complete prohibition of abortion is not consistent with traditional Jewish dogma.

“For Jews, this is not just a difference of opinion,” Manasseh says. “It’s not a matter of, ‘Oh, I’m pro-choice and you are pro-life, and we have to agree to disagree.’ So if you are taking a right away from me that my religion gives me, you don’t get to say your [religion] takes precedent over mine in the country you want to be a Christian country. That is not what America is about. That is not what the Constitution says. It becomes a legal issue when you are talking about Jews.”

Manasseh says the newest incarnation of the Janes will not be as clandestine as their earlier counterparts, nor will they be performing abortions. The Janes will visit college campuses in states that ban abortion to hand out care packages that contain Plan B pills, female and male condoms and birth control pills. They also will offer QR codes with information on how to get transportation to a state where abortion is legal, where to stay and how to get money for a bus or plane ticket.

“For Jews, this is not just a difference of opinion,” says Rabbi Tamar Manasseh. “If you are taking a right away from me that my religion gives me, your don’t get to say [your] religion takes precedent over mine in the country you want to be a Christian country.” (Photo by Matt Marton / ABA Journal)

“For Jews, this is not just a difference of opinion,” says Rabbi Tamar Manasseh. “If you are taking a right away from me that my religion gives me, your don’t get to say [your] religion takes precedent over mine in the country you want to be a Christian country.” (Photo by Matt Marton / ABA Journal)Ross and Manasseh both feel that the lack of abortion access will disproportionately affect low-income and women of color. Manasseh points out that over the years, Black women have become one of the most college-educated groups in the U.S.

“How do you derail that? You tell them they can’t get an abortion if they need one when they are a freshman in college, or you lock them up because they did get one. That is the quickest way to completely derail some of the brightest futures that this country may see.”

Missouri lawmakers considered legislation that would limit or prevent travel to other states to get an abortion, aware that women can circumvent bans by traveling to another state. Others have enacted bounty hunter provisions, testing the limits of state power to regulate abortion. In September, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., proposed a bill that would ban abortion nationwide after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

“Some conservative states have hinted at the broad use of criminal prohibitions on aiding and abetting, which could easily be applied to groups that perform abortions—or even those that provide referrals or basic information,” Zeigler says. “The tricky question is when or whether states will be able to enforce their laws outside of state lines. We don’t have much precedent in recent decades to know how courts will address that question.”

Navigating rocky terrain

During its annual meeting in August, the ABA’s House of Delegates adopted six resolutions, including one that upholds access to contraceptives and another that “opposes the criminal prosecution of any physician or medical or health care provider who provides or attempts to provide an abortion, or who encourages, helps, advises, gives information to, aids, assists or supports a patient with having an abortion.”

Also in August, the ABA Health Law Section announced the creation of a Dobbs-related task force, which was formed to provide information to members “whose clients are impacted by the complex health law issues related to Dobbs.”

The Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice and the Standing Committee on Pro Bono & Public Service will be collaborating with other ABA entities to develop a clearinghouse of resources for both attorneys and people seeking updates and legal information.

The ABA-led endeavors will help lawyers as they represent clients in different states with varying laws. For example, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt signed five abortion bans into law in 13 months, including two “bounty-hunting” laws.

The idea of prosecuting individuals who help a woman obtain medical services in a state where abortion is legal doesn’t make sense to Rabia Muqaddam, senior staff attorney at the Center for Reproductive Rights. “However, we know that these states are just chomping at the bit to find ways to restrict abortion access, and they are not going to be content with merely banning it within their state borders.”

Oklahoma’s bans have created legal confusion, for instance, in how they define a medical emergency. They also have conflicting information on issues such as ectopic pregnancies and exceptions for survivors of rape and abuse.

“The most recent ban that took effect has an exception to preserve a person’s life in a medical emergency. But the pre-Roe ban, which is also in effect, only has an exception to preserve a patient’s life,” says Muqaddam, who is hoping that the Oklahoma Supreme Court will interpret its own constitution to protect the right to abortion.

‘Great bodily injury’

In 1978, a 17-year-old rape victim became pregnant in California. In People v. Sargent (1978), California’s 4th District Court of Appeal held that “a victim of forcible rape who becomes pregnant as a result of that rape suffers great bodily injury.”

(Photo illustration by Sara Wadford / ABA Journal)

(Photo illustration by Sara Wadford / ABA Journal)According to rape and incest survivors, the mental trauma associated with the experience is one that many cannot escape without outside help. “I didn’t get any help for many, many years,” Ross says. “I self-medicated with drugs. I did a lot of destructive stuff.”

Ross also says it wasn’t easy being a young single mom. “It was very complicated to try and raise my son and try not to take my dysfunction out on him at the same time. It was a battle, she recalls. “As my son got older, we talked about this. I had to apologize to him because I was never able to give him unconditional love. Every child deserves unconditional love from their mother.”

According to Indiana lawyer Jim Bopp, the Ohio adolescent who was raped should have carried her baby to term instead of having an abortion. Bopp, general counsel for National Right to Life, an anti-abortion organization with over 3,000 local chapters, authored a model law that promotes abortion restrictions.

“She would have had the baby, and as many women who have had babies as a result of rape, we would hope that she would understand the reason and ultimately the benefit of having the child,” Bopp said in an interview with Politico.

In May, National Right to Life sent an open letter to state lawmakers from anti-abortion organizations containing the following: “The mother who aborts her child is also Roe’s victim. She is the victim of a callous industry created to take lives; an industry that claims to provide for ‘women’s health’ but denies the reality that far too many American women suffer devastating physical and psychological damage following abortion.”

National Right to Life did not respond to requests for comment.

Regardless of the debates around abortion, some victims of rape feel revictimized by flaws in the legal system that leave them without necessary resources, even when they make the choice to keep their babies.

At 14, Kaitlyn Urenda was on the swim team at her El Paso, Texas, high school. During a time when she should have been racking up medals and enjoying the exuberance of youth, Urenda was instead groomed and sexually assaulted by a gymnastics coach at her school. She became pregnant at 16 and eventually gave birth to a baby girl. “I didn’t tell anyone it was sexual assault,” Urenda says.

That’s because she didn’t realize it herself until receiving therapy years later. Urenda also was forced into a shared custody arrangement with her daughter’s father, a fight she says amassed $40,000 in attorney fees by the time she was 19. Years later, her abuser was accused and convicted of sexual assault involving three other students.

Urenda, now 30, is a single mom raising her 13-year-old daughter. She eventually graduated from college, and now she has a new dream: becoming a lawyer. She feels lawmakers who restrict abortion access don’t comprehend the amount of support women need, especially in cases of rape or incest.

“We cannot continue to make laws that don’t reflect our country’s morality,” says Urenda, who is a RAINN spokesperson and activist. “Until our morality is as high as that expectation, you cannot make laws forcing women to have children. … It’s a woman’s choice to have a say-so over her body and what happens to it.”

No doubt women voters had a say during the midterm elections in California, Michigan and Vermont, where measures enshrining abortion rights into state constitutions were approved. In Kentucky, voters rejected a bid to put an abortion ban into its state constitution. And early numbers indicated a “born alive” ballot measure in Montana would fail.

The fight for reproductive justice continues, and Ross, who is now a proud grandmother, says what we are seeing after the Dobbs decision is essentially the same battle she faced in the ’70s: “One of the reasons I still fight is that young girls today have a harder time getting an abortion now than I did 50 years ago.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.