As Other States Watch, Florida’s Redistricting Fracas May Set the Lines for the Future

Photo of Scott Fortune by Neil Rashba

The polls had closed only hours earlier when the electronic complaint sailed across the virtual transom over the federal courthouse door in downtown Miami just shy of 2 a.m. on Nov. 3, hitting the docket with a resounding thud.

Nearly two-thirds of the Florida voters who went to the polls the day before had cast ballots in favor of two state constitutional amendments that for the first time directly restrain lawmakers when they set out to draw new district lines for seats in the U.S. House and for both chambers of the Florida legislature.

But two incumbent politicians want to undo that vote and save their jobs by persuading the court to strike down the new rules. Though the voters spoke loudly, the representatives insist the job of line-drawing resides correctly now where it always has—with state legislators. U.S. Reps. Corrine Brown, an African-American Democrat from Jacksonville, and Mario Diaz-Balart, a Cuban-American Republican from Miami, filed the first of what likely will be endless lawsuits across the country claiming one side or the other is getting the short end of the redistricting stick. Both representatives say they’re protecting their constituents, not themselves.

The peculiar shape of Florida’s 3rd Congressional District. Illustration by Aman Khanna

LONG-TERM BENEFITS

Not a single line has been drawn yet in Florida, and likely one won’t be until the spring of 2012. Still, being first brings notice.

“I had been thinking about it for a long time,” says the pair’s lawyer, Stephen Michael Cody of Coral Gables. “Once we got the election results in, I talked to Corrine and I talked to Mario. They said it was a go.”

Though always a rich source of political theater and litigation, redistricting has attracted extra attention in the wake of the Republican rout of the Democrats in November. Besides wresting control of the U.S. House, Republicans gained control of both houses in 25 states, up from just 14 before the election.

Redistricting is a huge deal. While election results are good for just a couple of years, clever redistricting can rearrange the political table for decades. And in Florida, voters of both parties were evidently fed up with business as usual by the time the midterms rolled around.

Though barely a third of Florida’s 11.2 million eligible voters cast ballots, almost 63 percent favored two nearly identical amendments to the state constitution setting new rules for drawing congressional and legislative districts.

Legislators of both parties historically had freelanced and gerrymandered the state from top to bottom for personal job security and partisan advantage. Under the new amendments, legislators could not favor or disfavor incumbents or deny racial and language minorities the opportunity to participate in politics and elect the candidates they want. To prevent gerrymandering, which often results in virtual Rorschach cards dotting the map, districts must be contiguous; as compact and equal in population as possible; and, wherever feasible, follow city, county and geographical boundaries.

The new rules face considerable resistance from opponents who deride the amendments as left-wing sleight-of-hand designed to overcome a crippling Republican legislative majority. Last summer, the Florida Supreme Court beat back yet another proposed amendment Republican legislators pushed to knock the redistricting measures off the ballot.

But backers say the amendments enjoy wide bipartisan support, despite the fact that they face persistent political hostility and even thornier issues regarding minority representation.

“I think it will be a challenge, but yes, I think it can be absolutely done,” says Coconut Grove lawyer Ellen C. Freidin, campaign chairwoman for FairDistricts Now, which spent four years and $9 million getting the measures on the ballot. “I think it will be able to accommodate minorities.”

On Jan. 4, just three days after he took office, newly elected Republican Gov. Rick Scott secretly withdrew the state’s federally required request for Justice Department approval of the new constitutional language.

Scott also appointed Kurt Browning as secretary of state. In 2010, Browning retired as secretary of state to campaign against the new election rules. Now reappointed by Scott, he earns both a pension and a salary as the state official tasked with enforcing—or not enforcing—the rules he campaigned against.

As redistricting committees in both chambers tested public access software and planned public hearings, the Florida House intervened in the court challenge on the side of the Congress members. They asked the court to strike the law as a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s elections clause, which they say bestows on them exclusive mapmaking power. A spokeswoman for Republican House Speaker Dean Cannon says the legislative cartographers merely want to know the rules of the road before they get started. But their complaint only asks the court to rid them of the law and nothing more.

It’s much the same in most states that let legislators call the tune to the redistricting dance. Though 13 have tried to reduce or eliminate partisan influence by naming citizens commissions to draw the lines, elected officials typically get to appoint the members.

The only other significant redistricting change voters approved in November created a California citizens panel that may go the furthest in neutralizing politics. By mid-February 2010—nine months before the election—nearly 31,000 people had applied for spots on the 14-member commission, to be composed of five Democrats, five Republicans and four independents or minor party members. After auditors narrowed the field to 60, legislators could only remove 24. Auditors then selected the first eight members randomly, and those panelists chose the remaining six among themselves.

Some question the motives of Rep. Corrine Brown (shown at a 1999 news conference), who finds herself in opposition to other African-American legislators and the NAACP in regard to to Florida redistricting legislation. Photo by AP/Peter Cosgrove

COMING TO THEIR CENSUS

Regardless of how they do it, the partisan legislative pas de deux steps off anew every decade with the U.S. census. The federal head counters, through a related process called reapportionment, determine how many congressional seats each state will have according to population gains and losses over the past decade. Thus, states with shrinking populations may stand to lose seats, while those gaining new residents could increase their representation. Florida’s population grew from 15.9 million in 2000 to 18.8 million in 2010, increasing its congressional delegation by two seats to 27 for the 2012 elections.

After the census finishes its work, it’s off to the legislatures. There, lawmakers divvy up the territory. Redistricting often becomes an acrimonious partisan frenzy as Democrats and Republicans both try to hold precious real estate and votes, often gerrymandering districts by twisting them into bizarre shapes to benefit their own.

Along with the usual partisan complaints comes the ubiquitous litigation. Racial minorities and non-English speakers often are first to line up outside the courthouse with complaints of being shut out of effective representation. Hispanics, as the nation’s largest minority, are expected to press the point, especially in states like Florida.

In 2010, the total number of Hispanics in the U.S. far exceeded the number of blacks. Their 50.4 million represents 16.3 percent of the 308.7 million total U.S. population. The African-American community, at 38 million, continued to expand, but it now represents only 12.6 percent of the U.S. population.

In Florida’s 25 current congressional districts, Hispanics or blacks form a majority or near majority in six. In the 120-member Florida House, Hispanics hold 11 seats, while blacks occupy 13. The 40-member Senate seats three Hispanics and 13 blacks. In 2010 the state’s Hispanics numbered 4.2 million. They accounted for 51 percent of Florida’s growth and 22.5 percent of its population.

But redistricting is not just about race; it’s about incumbency. And incumbents from both parties and all races scurry to protect their jobs, even when they have no say in the process. Reps. Brown and Diaz-Balart publicly proclaim their lawsuit aims to ensure constituents can elect the candidates of their choice—which more often than not turn out to be the incumbents themselves.

Federal law also plays a heavy hand. Under the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination—chiefly the states that were part of the former Confederacy—must “preclear” with the Justice Department any changes that may affect minority power at the polls. This season, as in previous decades, fervor is building for judicial repeal of the provision—called Section 5—as outdated and unnecessary.

Lawyers for civil rights groups are closely watching a case called Shelby County, Ala., v. Holder, under way before a three-judge panel in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, the alternative approval forum to the Justice Department administrative route. In a broad assault, the county’s tiny community of Calera wants Section 5 declared unconstitutional on its face to preserve a redistricting scheme that eliminated the only African-American from the Calera city council.

Judges have faint appetite to trash Section 5. The last time the U.S. Supreme Court had a crack at the provision was in 2009 in Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder, when by an 8-1 vote the justices avoided constitutional questions and ducked passing judgment on Section 5.

Congress has shown no interest in killing the Voting Rights Act either. In 2006, it was extended for 25 years by votes of 98-0 in the Senate and 390-33 in the House. In Florida, Section 5 covers five counties, and the Justice Department must approve the amendments before and after the lines are drawn. Gov. Scott’s withdrawal of Florida’s Section 5 request got him and his appointed secretary of state, Browning, sued by the American Civil Liberties Union and other rights groups backing the amendments. Scott’s predecessor, Republican Charlie Crist, supported the amendments and had filed the request in the fall as soon as the election results were certified.

“I was dumbfounded when he withdrew it,” says former Democratic state Sen. Dan Gelber of Miami Beach, counsel to Fair Districts and an unsuccessful candidate for attorney general last year. “It was like snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.”

When reporters discovered what Scott had done three weeks later, a spokesman explained it as part of a broad rules freeze Scott had promised as a candidate. His one-sentence letter to Justice offered no reason. Scott did not respond to continued interview requests.

The case against Scott was mooted in late March when the legislature resubmitted the request, along with backup material explaining how the amendments won’t disturb minority voting rights. They moved after Scott finally asked them who was supposed to file the letter or what information to include. Legislators concluded the authority belongs either to them or the attorney general—and not the governor.

Indeed, the Florida governor’s role is limited and leaves him largely out of the loop. While the governor must approve the congressional districts, only the Florida Supreme Court and U.S. Justice Department need to approve the legislative changes.

It’s anyone’s guess whether the new rules will end the potential for political mayhem already wired into the system. But despite new laws on the books, Democrats may not be able to do much to help themselves.

ROLLING REPUBLICAN

Before the last election, Florida had 4.6 million registered Democrats and 4 million Republicans. Still, the GOP long has enjoyed oversize majorities in both the legislature and the congressional delegation. Today it holds veto-proof majorities in the state Senate, at 28-12, and the House, at 81-39. Republicans occupy 19 of the 25 seats in the current congressional delegation.

This occurs partly because Florida Democrats commonly live in highly concentrated districts in coastal urban areas like Miami, Jacksonville and Tampa, where they often account for substantially more than half the voters. Thus, in a hypothetical urban district with 100,000 voters, 75,000 could be Democrats. Assuming it only takes 50 percent of the vote plus one to elect a candidate, the remaining 25,000 Democratic votes are effectively “wasted.”

That leaves the rest of the state to Republicans, typically denizens of geographically expansive suburban and rural areas. Republicans occupying more land can, in turn, control more districts with fewer votes.

Democrats wielded similar advantages until the 1980s, when the South underwent party realignment after President Ronald Reagan’s election, with many old-line Democrats jumping to the Republican Party.

With help from 39th District mapmakers, Rep. Geraldine Thompson of Orlando could form a coalition with Hispanics to gain a majority.

“African-Americans are packed into so very few districts that everything else around them is bleached,” complains Geraldine F. “Geri” Thompson, a black state representative from Orlando who is eyeing a state Senate seat for 2012. “In Orlando, you have a single African-American legislator—that’s me—and one senator. We have room for more.”

But residential patterns don’t explain why black Rep. Brown finds herself on the opposite side of the issue from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and many other black legislators.

Some chalk up the sad state of Democrats in Florida to the national wave of voter dissatisfaction with the party. Political scientists generate one computer model after another to explain the Democrats’ plight. But those involved say redistricting controversies just aren’t that complex.

“The driver on this is incumbency,” says FairDistricts lawyer Gelber. “This is about incumbents wanting to pick their voters.”

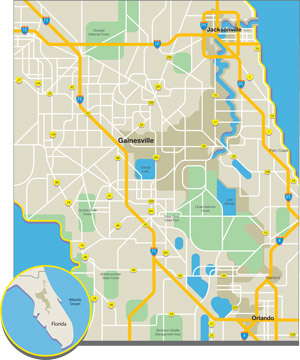

Rep. Brown’s 3rd Congressional District, regarded as one of the most severely gerrymandered anywhere, was created in 1992. The idea was to include African-American communities in the old plantation country along the St. Johns River, one of the few regions where newly freed slaves could buy land after the Civil War. White Republican legislators were willing to concede a few seats to minorities by consigning high concentrations of minority voters to a handful of districts.

The results can be ridiculous. Today Brown’s district stretches for 140 miles south from her northeast Flor ida Jacksonville base to Orlando, expanding and contracting as needed to suck in as many black communities as possible. The district is just a few feet wide at some points.

“So often, it’s just simple horse-trading,” Gelber says. The give-and-take made Brown the first African-American from Florida elected to Congress since Reconstruction.

Diaz-Balart, on the other hand, pulled an inside job in 2002 to get his original 25th District the way he wanted it. That’s because, as state House redistricting chairman, he drew the lines himself. He wound up with western Miami-Dade County, the Florida Keys and the Everglades.

Diaz-Balart, who failed to acknowledge numerous interview requests, ran unopposed in the district’s first election in 2004; but his margins of victory steadily shrank as more Democrats moved in. So in 2010 he packed up and relocated to the adjacent 21st District, the one he is now defending in court.

Squeezed against the eastern edge of the Everglades, the 21st District includes a chunk of Broward County, middle-class suburbs in Miami-Dade and heavily Cuban-American Hialeah. The district had one more advantage: It was represented by his brother, Rep. Lincoln Diaz-Balart. Lincoln announced his retirement in 2010, and brother Mario ran unopposed.

Significantly, pre-election polling last fall by the Pew Hispanic Center in Washington, D.C., showed two-thirds of the nation’s Latino voters intended to pull the lever for Democrats. But Miami-Dade Cuban-Americans form a unique anti-Castro bloc and overwhelmingly vote for Republicans.

Diaz-Balart “moved into his brother’s district because he’ll never face a serious opponent,” says Howard Simon, executive director for the Florida ACLU.

“Why is he climbing the walls over [amendments] 5 and 6?” Simon wonders. “It’s not for personal advantage. It’s for partisan advantage. He’s got job security.”

The ACLU is among several civil rights groups that have intervened as defendants to oppose the Brown and Diaz-Balart challenge, as well as filing the separate complaint against Gov. Scott over the Section 5 withdrawal. They find themselves opposite Brown, a brash and polarizing figure who did most of the talking last year during the campaign against amendments 5 and 6.

Brown apparently doesn’t care for questions about her fight against the new rules for redistricting. She didn’t respond to interview requests. And last year she hung up five minutes into a telephone radio interview when callers wanted to know about her opposition to the amendments.

Even before she landed in Congress, state and federal authorities investigated her for mishandling campaign contributions and government funds. She often complains the criticism or opposition is racially motivated. But she seems politically unassailable.

“My philosophy has always been that, when the community has a cold, the African-American community has pneumonia,” Brown testified in an equal protection challenge to her original black majority 3rd District brought by radio talk show host Andy Johnson, an unsuccessful candidate for her seat.

“The bubba I beat couldn’t win at the ballot box,” Brown complained to The New Republic, “[so] he took it to court.”

Illustration by Aman Khanna

COURT-DRAWN LINES

In 1992 a court drew the original 3rd district lines Johnson later complained about after legislators failed to agree on the boundaries. Even compared with today’s version, that district was a doozy, with an in verted horseshoe shape stretching across north central Florida, beginning in Orlando at one end then snaking north capturing black communities along the way before reaching Jacksonville, then turning west and dipping south through Gainesville and Ocala. A second court dumped that map in 1996 and ordered legislators to draw new lines that remain today.

Regardless of the district’s configuration, the opposition Brown drew last year was the first she had encountered since 2002, when she still won easily with 59 percent of the ballots cast. The 2010 campaign was steeped with questions about the size and shape of the 3rd District.

Courts historically have accepted wacky-shaped districts like Brown’s in order to create districts that can generate minority representation. But can that be accomplished in districts created within the limits of Florida’s new election rules? Brown’s district, for instance, covers nine counties.

Scott Thomas Fortune may know that better than anyone. Brown beat Fortune in the 2010 Democratic primary with 80 percent of the vote. Fortune comes from upscale Jacksonville Beach, a barrier island community off the Atlantic coast where 90 percent of the residents are white. Fortune had no problem picking up Brown’s racial code for him.

“Corrine Brown kept referring to me as ‘that lawyer from the beaches,’ ” Fortune says.

The continuing controversy over Brown’s district lines proved to be too much for Fortune to ignore. So one June weekend he packed up his van, along with a giant map and a video camera, and set out on a three-day tour of the serpentine 3rd District that took him from Jacksonville to Orlando.

He drove from one small town to the other, most with just a few thousand residents, most of which were divided by district lines separating Republican white voters from Brown’s Democratic black voters. Sometimes the district boundaries run along railroad tracks or right down the centerline of a town’s main drag. It reminded Fortune of old-fashioned segregation. In less populated areas, legislators connected African-American communities almost literally by a thread, linking them with no more than 10-foot-wide strips of vacant land along the roadside.

One town, Apopka, has a population of about 27,000. Still, it has three congressmen.

“This town has been carved up for nothing more than political gain,” Fortune says on his video while sitting behind the wheel.

His trip ended in Orlando, where he got acquainted with Rep. Thompson at a festival marking the emancipation of African-Americans from slavery. Thompson knows she needs help from the mapmakers if the still-mythical state Senate seat she’s considering is ever to become hers.

“I don’t know what opportunities will open after we draw the map,” Thompson says. One possibility, which courts have approved, is drawing a district where blacks don’t constitute a majority but still have the voting strength to elect whom they want by forming crossover coalitions with other voters. Thompson might find attractive coalition partners among new Hispanic residents who in the last decade have inundated central Florida.

Latino leaders like Thompson’s neighborhood, too, and they hope to get a seat to accommodate some 900,000 Hispanics who live along the Interstate 4 corridor—from Tampa on the Gulf Coast, northeast to Thompson’s Orlando backyard, then on to Daytona Beach on the Atlantic.

But a 2009 Supreme Court decision that started with the 2000 census may stand in the way of crossover districts. In Bartlett v. Strickland, a plurality of the justices held that the Voting Rights Act doesn’t offer minorities protection from government actions that damage their voting strength if they account for less than 50 percent of a district’s voting age population. (Blacks recently eked over the 50 percent mark in Brown’s district, so the decision presumably would not affect it.)

Now, with the next redistricting cycle here, civil rights lawyers are waiting to see whether the justices really meant what they said. Kristen Clarke isn’t so sure they did.

“We’ll have to look very closely case by case to see if those coalition districts can give minorities opportunities,” says Clarke, political participation co-director for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “I think line-drawers could find themselves in hot water if they go out and dismantle these districts.”

Meanwhile, the Florida litigation rolls on, with more cases likely to come later. That’s a problem, too, because Florida’s legislative schedule for completing redistricting is one of the nation’s latest. Final approval even can overlap with the June 18-22, 2012, qualifying period when candidates must submit petitions and other documents to get on the ballot that fall.

So folks who file lawsuits later in the process may find their backs against the wall, with abbreviated discovery and other evidence gathering pushed there along with them. Some parties, thus, may be unable to fully develop their cases—a factor some say favors incumbents who already know the lay of the land, what political bodies are buried beneath it and where. Fair Districts lawyer Gelber says legislators could avoid eleventh-hour migraines simply by working faster to finish earlier.

“You could litigate it for some time,” he says, “but you have to give voters a fair chance to make an informed choice.”

Last updated Aug. 16 to fix a Web production error. The caption for the Scott Fortune image was inadvertently inserted into the main body of the article.