A Smokin' Body: Cancer Images Are Lighting up a First Amendment Blaze

Photo U.S Food and Drug Administration

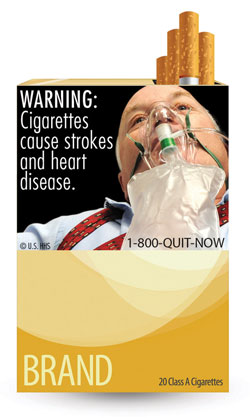

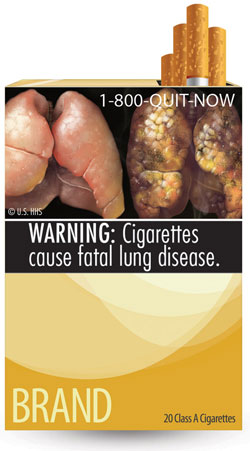

Photo U.S Food and Drug Administration

It’s a burning controversy that continues to smolder—and use any other smoking puns you prefer—as the dispute over requiring graphic anti-cancer images on cigarette packs lights up a First Amendment fire.

The battle over the constitutionality of new warnings mandated by the Food and Drug Administration to appear on cigarette packages is being fought in the lower federal courts. And two cases have already been appealed as tobacco firms and the government get heated over the FDA order.

In 2009, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed into law the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which gave the FDA additional authority to regulate tobacco products. The FDA rule requires nine new textual warnings and graphic images to appear prominently on cigarette packages.

The textual warnings include: “Cigarettes are addictive,” “Cigarettes cause fatal lung disease,” “Cigarettes cause cancer,” “Cigarettes cause strokes and heart disease,” “Smoking during pregnancy can harm your baby,” “Smoking can kill you,” “Tobacco smoke causes fatal lung disease in nonsmokers” and “Quitting smoking now greatly reduces serious risks to your health.”

The FDA rule also requires the posting of one of nine graphic images, including a cadaver on an autopsy table, horribly damaged teeth and a man exhaling smoke through a tracheotomy opening in his neck. The rule requires the text and images to encompass 50 percent of the front and back of all cigarette packages.

Tobacco companies challenged various provisions of the statute, including the mandated requirement of the graphic warning labels, which the companies claim amounts to the government confiscating the tobacco packages for their own advocacy. The companies contended in federal lawsuits in the districts of Western Kentucky and the District of Columbia that the warning labels amounted to unconstitutional compelled speech in violation of the First Amendment.

COMPELLING QUESTIONS

Last November, U.S. District Judge Richard J. Leon for the D.C. court ruled in R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. United States Food and Drug Administration that the companies were entitled to a preliminary injunction based on their First Amendment arguments. On Feb. 29 he raised it to a permanent injunction. The government had argued that the warning requirements were simply a reasonable disclaimer on commercial speech or advertising that always has received a lower level of free speech protection.

However, Judge Leon reasoned that this lower level of scrutiny applied only to disclaimers of “purely factual and uncontroversial information.” To Leon, the images amounted to “government advocacy” and compelled commercial speech that required the application of strict scrutiny.

Under this tighter standard, a government regulation must advance a compelling interest in a narrowly tailored way. But Leon said that “the government’s emphasis on the images’ ability to provoke emotion strongly suggests that the government’s actual purpose is not to inform but rather to advocate a change in consumer behavior.”

New York City-based attorney Floyd Abrams, who represents the Lorillard Tobacco Co., a plaintiff in the case, says that Leon accurately questioned the government’s requirements as crossing the line from permissible information to consumers to impermissible government advocacy on the backs of private companies’ advertising.

“The ruling didn’t come as a surprise because the law seemed to us quite strongly in our favor,” says Abrams, a First Amendment expert. The decision is a “major First Amendment victory,” he adds.

“There’s no doubt it was compelled speech, but there’s also no doubt that warnings may be required by tobacco companies and others on their products,” Abrams says.

“What the government could not successfully respond to were Judge Leon’s repeated questions about how he should determine what sort of statements were ‘factual and uncontroversial,’ ” says Abrams, referring to guidelines set in the 1985 U.S. Supreme Court case Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, “and what amounted to government advocacy—the latter being something the government was plainly free to engage in but not to require the seller of the lawful product to do.”

“This sort of graphic imagery is way over the top and does amount to compelled speech,” says Richard Kaplar, vice president of the Media Institute, an Arlington, Va.-based nonprofit research foundation.

“It certainly is not a narrowly tailored means and represents the government asserting its own political agenda into the realm of speech. I think that Judge Leon is exactly right—that the government’s action is unconstitutional and does amount to compelled speech,” Kaplar says. “I hope and trust that an appellate court would find the same way. After all, it is still a lawful product marketed to adults.”

But Northeastern University law professor Richard A. Daynard, who heads the school’s Public Health Advocacy Institute and chairs the Tobacco Products Liability Project, finds fault with Leon’s ruling.

“As Judge Leon notes—and pooh-poohs—4,000 American children and teenagers experiment with cigarettes every day, and 1,000 of them proceed to become addicted,” Daynard says. “He doesn’t mention that half of all regular smokers die from their cigarette use, taking many years off their life expectancy.

“Anything that discourages them from smoking, such as graphic warnings that break through the clutter of legally required information on consumer products that few consumers read, will save many lives,” Daynard adds. “With more than 400,000 Americans dying of cigarette-caused diseases each year, smoking remains by far the leading preventable cause of death and disease.”

Leon “is utterly indifferent to the compelling public interest in promoting public health, and to the lives that will be lost as a result of delaying the graphic warnings,” Daynard contends. “He completely misunderstands the nature of mass communication. He wouldn’t last 10 minutes on Madison Avenue with his notion that you can educate people without engaging their emotions.”

The government has appealed the ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Photo U.S Food and Drug Administration

HEADED TO THE HIGH COURT?

Leon’s ruling, which received a lion’s share of the media attention, is not the only litigation involving tobacco regulation. In January 2010, U.S. District Judge Joseph H. McKinley Jr. for the Western District of Kentucky reached a different result than Leon and rejected various constitutional challenges to the federal statute.

The lawsuit in Commonwealth Brands Inc. v. United States featured facial challenges to numerous parts of the new law, including bans on outdoor advertising, color graphics and other features. But the suit also challenged the new tobacco warnings and upcoming images. Judge McKinley upheld the provision, writing that “the court does not believe that the addition of a graphic image will alter the substance of such messages, at least as a general rule.”

The government appealed the decision—now known as Discount Tobacco City & Lottery v. United States—to the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Cincinnati, which heard oral arguments late last July.

Steven A. Delchin, a Cleveland attorney with the law firm of Squire Sanders, which maintains the Sixth Circuit Appellate Blog, does not believe the circuit will be swayed much by Leon’s ruling.

“It is important to note that the case before Judge Leon in the District of Columbia is different than the case before the 6th Circuit,” Delchin says. “As Judge Leon himself noted in his opinion preliminarily enjoining the FDA’s final rule establishing graphic warnings for cigarette packaging and advertising, the D.C. case is ‘wholly separate’ from the 6th Circuit case, ‘both factually and legally.’ ”

Whatever the outcome of the cases before the D.C. and 6th Circuits, the legal battles will continue. Obama criticized the tobacco companies for opposing the labels, and his administration appears committed to defending the new tobacco law and the graphic image requirements.

That means the dispute will not flame out like flickering embers but continue blazing, probably all the way to the Supreme Court.

Editor’s note: In a March 19 ruling (PDF), the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed most of the district court’s decision, upholding the constitutionality of the statute. The appeals court, however, reversed the lower court by striking down a provision that barred the tobacco companies from using color or imagery in their ads.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.