A Real-Life Grisham Story: Denial of Jury Award Marks Disappointing Postscript to Death Row Release

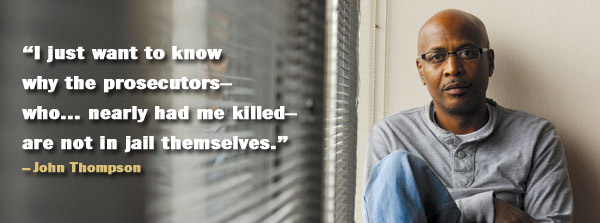

Photo by Jennifer S. Altman

John Thompson has had worse days than the one in late March when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 against him in his civil rights case. After all, the Louisiana man spent 14 years on death row for a murder he didn’t commit and he once came within weeks of being executed.

But Thompson also has had better days, such as when the jury in his retrial, after having been presented exculpatory evidence not disclosed to his lawyers the first time around, acquitted him of murder after 35 minutes of deliberations.

While Thompson has been a free man since that 2003 acquittal, the court’s March 29 decision in Connick v. Thompson threw out a $14 million civil jury award he won against the Orleans Parish district attorney’s office.

The majority held that a district attorney’s office cannot be held liable for a failure to train its prosecutors stemming from a single violation of the court’s landmark 1963 decision in Brady v. Maryland. In that case, the court held that due process requires prosecutors to turn over evidence to the accused.

The Connick majority drew a sharp dissent from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. “The record in this case abundantly shows flagrant indifference to Thompson’s rights,” Ginsburg said from the bench.

It also was rebuked by retired Justice John Paul Stevens, who made a rare comment about a court decision. In a May 2 public appearance, Stevens suggested that Congress should step in with a law that would make it easier for public agencies to be held strictly liable for the torts of their employees. Doing so “would produce a just result in cases like Thompson’s in which there is no dispute about the fact that he was harmed by conduct that flagrantly violated his constitutional rights.”

CALL FOR CULPABILITY

The decision was a lesson in disappointment for Thompson, now director of a support group for exonerated inmates.

“I don’t care about the money,” he wrote in an op-ed essay in the New York Times days after the decision. “I just want to know why the prosecutors—who hid evidence, sent me to prison for something I didn’t do and nearly had me killed—are not in jail themselves. There were no ethics charges against them, no criminal charges; no one was fired and now, according to the Supreme Court, no one can be sued.”

Many in the legal community are debating the Brady disclosure obligations and the proper role of training in prosecutors’ offices.

“What we really need to be thinking about is how to create a system under which these things don’t happen in the first place,” says New York University law professor Rachel E. Barkow, who has studied Brady issues.

Thompson’s story reads like a real-life plot out of a John Grisham novel. In 1985, he and another man were arrested and charged in the murder of a New Orleans businessman. In their investigation, Orleans Parish pros ecutors linked Thompson to the armed robbery of three siblings committed three weeks after the Decem ber 1984 murder. During that robbery, the assailant’s blood stained one of the victim’s pant legs. A swatch was tested by a crime lab, but the results were never revealed by prosecutors to Thompson’s attorneys.

Prosecutors chose first to try Thompson in the armed robbery, for which a conviction could be invoked in support of the death penalty. At least four prosecutors in the Orleans Parish district attorney’s office knew of the blood evidence, but none of them disclosed that to the defense. And just before the trial one of the prosecutors, Assistant District Attorney Gerry Deegan, removed the bloody swatch from the evidence in the case to keep its existence unknown to the defense.

Thompson was convicted of the armed robbery and later of the separate murder, and still the blood evidence went unknown to his lawyers.

EVIDENCE EMERGES

Defense lawyers worked for years on post-conviction proceedings, but without success. In 1999, Louisiana set an execution date for Thompson. Meanwhile, a defense investigator unearthed a microfiche copy of the lab report. It identified the armed robber’s blood as Type B. Thompson’s blood is Type O.

Microfiche records showed the report had been delivered to a prosecutor in 1985. Thompson’s lawyers contacted that prosecutor, who told them even more. In 1993, after finding out he was terminally ill, Deegan confessed to a friend that he had suppressed the blood evidence in the armed robbery case. Deegan was urged to confess, but died in 1994 without revealing his secret.

With the crucial blood evidence finally revealed, Thompson’s execution was stayed; the armed robbery conviction was thrown out. The murder conviction was later set aside by a state appellate court, but the district attorney’s office insisted on retrying Thompson.

Bolstered by evidence not previously disclosed to him, Thompson was able to convince the second jury that he did not commit the murder. (The acquaintance arrested with him in 1985, whom Thompson’s lawyers implicate as the murderer, died in 1995.)

Thompson sued Harry F. Connick, the longtime Orleans Parish DA, alleging that Connick and other prosecutors had violated his civil rights by wrongfully withholding Brady evidence. The $14 million jury verdict he won was affirmed by the evenly divided en banc 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at New Orleans.

But Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote the majority opinion, noted that the civil jury had found no unconstitutional policy in the district attorney’s office that caused the Brady violation. To recover damages from the government agency, Thompson had to prove deliberate indifference based on a failure-to-train theory.

But “failure to train prosecutors in their Brady obligations does not fall within the narrow range” of single-incident liability, Thomas said. While a police officer would obviously need such training, lawyers arrive at a prosecutor’s office already trained in the law, he said. Thomas was joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony M. Kennedy and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

DISSENTERS CITE NEED TO TRAIN

In dissent, Ginsburg said that what happened to Thompson “was no momentary oversight.” Connick hired staff members right out of law school, she noted, and because of high turnover, inexperienced prosecutors quickly became supervisors charged with training the newest additions. Instruction on Brady and its application was nonexistent, Ginsburg said.

University of Virginia law professor Brandon L. Garrett says it was ludicrous for Thomas to suggest there is no obvious need to train prosecutors on Brady.

“Good prosecutors’ offices would find the idea ridiculous, too,” says Garrett, author of Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong, a study of wrongful convictions published in April. “It’s not because they might get sued years later. But prosecutors and [defense] attorneys realize they need to share good information.”

Scott Burns, the executive director of the National District Attorneys Association, says prosecutors “are always open to more Brady training.” But his group welcomed a ruling that makes it more difficult to hold prosecutors’ agencies liable for disclosure errors.

“I don’t know how you train to keep someone from that very rare instance where [a prosecutor] violates the rules and is borderline criminal,” Burns says. “This was an anomaly, and I would take issue with anyone who said it was pervasive throughout the system.”

University of Pennsylvania law professor Stephanos Bibas says Thompson has a sympathetic case, but the Supreme Court majority got it right on the constitutional standard for holding the prosecutor’s office liable.

“You feel sorry for Thompson here,” says Bibas. “But the facts obscure what this case means in general because it is an extreme case.”

Bibas helped lead a working group focused on improved Brady training as part of a 2009 symposium at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Among the group’s conclusions: Both formal and informal training programs are needed, and police and crime labs must also be kept aware of their obligations.

NYU’s Barkow, who participated in the Cardozo symposium, says Thomas could have done more to emphasize lawyers’ obligations to disclose evidence.

“I would have liked to see a little bit more about the obligations of the bar when it comes to Brady,” Barkow says. “Sometimes the court comes together and talks about the legal profession and what it should be doing. I see this as a lost opportunity.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.