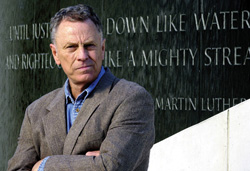

A Crusader's Reward: Morris Dees to Receive 2012 ABA Medal

AP Photo/Dave Martin

Four decades ago this month, a young lawyer from Alabama had an idea: Sue two organizations for damages stemming from the conduct and actions of their employees or members.

The organizations were the Republican National Committee and the Committee for the Re-election of the President. The individuals were five “burglars” who had broken into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C., on June 17, 1972.

The lawyer was Morris Dees, who at the time was serving as campaign finance director for George S. McGovern, who would become the Democratic candidate running against Richard Nixon in that year’s presidential race. After reading that the men arrested in the Watergate break-in had connections with the RNC and CREEP, Dees contacted McGovern’s campaign manager.

“I called Gary Hart” [a presidential candidate in the 1980s], says Dees, “and I said, ‘Gary, I smell a rat here. I say, let’s sue them.’ ”

The lawsuit eventually settled for a few hundred thousand dollars—a result that displeases Dees even to this day. He thinks the recovery against the RNC and CREEP could have been in the millions.

But Dees soon found other ways to put his unique legal theory to effective use. Starting in 1980 and continuing for the next three decades, the Southern Poverty Law Center, which Dees co-founded in 1971, filed a series of historic and highly successful civil lawsuits seeking to hold various chapters of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations responsible for the wrongdoings of their members. And he’s got the death threats to prove it—at least two dozen by his count.

In 1984, for instance, Dees filed Donald v. United Klans of America in federal district court on behalf of the mother of Michael Donald, who had been lynched by two Klansmen three years earlier in Mobile. The jury’s verdict: $7 million. The judge awarded the plaintiff the deed to the United Klans’ headquarters.

In one of the most recent cases, the SPLC won a $2.5 million judgment against the Imperial Klans of America and its imperial wizard, Ron Edwards, for the brutal beating of a Latino teenager at a Kentucky county fair in 2006. The Kentucky Supreme Court upheld the verdict in March.

PURSUING DREAMS

In August, the ABA will present Morris Seligman Dees Jr. with its highest honor, the ABA Medal. The association’s Board of Governors selected him as this year’s recipient in June, and he will receive the medal during the House of Delegates session at the 2012 annual meeting in Chicago. Previous recipients include Leon Jaworski, U.S. Supreme Court Justices Thurgood Marshall and Sandra Day O’Connor, and the Rev. Robert F. Drinan.

“Morris has done some incredible work and had amazing success in the arena of civil rights,” says H. Thomas Wells Jr., a fellow Alabamian who nominated Dees for the medal.

“Morris Dees is known as the lawyer who bankrupted the Ku Klux Klan and effectively put them out of business, but he’s accomplished so much more. Morris has dedicated his life to public service,” says Wells, a shareholder at Maynard Cooper & Gale in Birmingham who served as ABA president in 2008-09.

Dees was born in 1936. His father was a poor cotton farmer in Mount Meigs, just east of Alabama’s state capital of Montgomery. Their house didn’t have running water, and the family couldn’t always afford the electric bill. But in an environment where racism was rampant, the elder Dees taught his son to treat their African-American neighbors as equals.

Pressured by his father, Dees attended the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, where he received his law degree in 1960. Dees met Millard Fuller while at the university. The pair started a direct-mail marketing and publishing business, which paid for their law schooling. The company continued to grow after they graduated, and it ultimately made them millionaires.

The company’s success also allowed them to pursue other dreams. Fuller went to Africa, where he helped build housing. What he learned there helped inspire him to create Habitat for Humanity. Fuller died in 2009.

Meanwhile, Dees was drawn to the growing civil rights movement. In 1963, he had used his position as a Sunday school teacher to raise money for the victims of the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, in which four girls died. In 1965, he helped work for passage by Congress of the Voting Rights Act. That same year, he drove some of his black friends to Selma to join protests—a move so infuriating to some of his family members that they suggested he change his name.

INSPIRED BY CLARENCE DARROW

But Dees recalls that his real epiphany occurred one winter night in 1968, when he was snowed in for several hours at the Cincinnati airport waiting for a flight to Chicago. “I walked over and picked up a paperback book called The Story of My Life by Clarence Darrow,” says Dees. “A lot of people don’t realize that he was a general counsel for the railroad and he watched them hire thugs that beat up the workers, burned rail cars and blamed it on them. So he just walked in one day to the president of the railroad and said, ‘Look, my heart is on the other side of this fight.’ I read the whole thing during the night and I just made my mind up that I was going to do full time what I had been dabbling at and things that I really wanted to do.”

Dees sold the direct-mail company in 1969, using the funds to beef up his legal operation in Montgomery, which two years later became the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The first major case came that year, when Dees sued the Montgomery YMCA for its policy of segregation, which meant that black children could not attend summer camp. Smith v. YMCA landed in the courtroom of legendary U.S. District Judge Frank Johnson, who had previously ruled that the city had to integrate its public swimming pools.

“It was a big deal because Montgomery officials closed the parks and pools and cemented them up because they didn’t want to integrate parks and pools,” Dees says.

Dees uncovered a secret contract between the YMCA and the city to have a joint recreation program. The agreement called for the city to operate some programs, such as youth baseball, because there was no objection to them being integrated. Meanwhile, programs that city officials wanted to keep segregated, such as swimming, were turned over to the YMCA.

As Dees explains it, the suit created the possibility of “putting little white girls in the swimming pool with little black boys, and that was a no-no in Montgomery. I wasn’t too popular.”

But, he says, “Judge Johnson came back with a sweeping injunction, and it was really the first time a nonprofit group was ever integrated, and we proved that there was coordination and support from the city.”

At 75, Dees doesn’t sound like he’s ready to slow down. “There’s still so much more to do,” he says. “We are doing a lot of individual cases and we have a major juvenile justice project. The schools to prison pipeline must be addressed. Klan Watch is still doing tremendous work and we have a team going to law enforcement agencies across the country doing 30 to 50 seminars a year on hate crimes.”

In court and out, Dees, who once dreamed of being a Baptist preacher, often cites scripture, particularly Amos 5:24 in the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible): “But let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.