Costly Collisions: A small-town personal injury case sends a powerful message to the trucking industry

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal

In Gadsden County, Florida, last October, six jurors and an alternate settled in for a long day in front of their home computers and mobile devices to hear a personal injury case. Among them was a pastor, a chiropractor and a state government worker.

The judge, presiding from his computer inside the century-old Gadsden County courthouse in downtown Quincy, population about 7,000, asked everyone to be ready for the Zoom trial by 8:30 a.m. Across the street in a rented office, the plaintiff’s legal team flipped open their laptops and prepared to make their arguments.

One of the plaintiff’s attorneys was Ben Crump, who at the time was juggling some of the nation’s highest-profile civil rights cases on behalf of families whose loved ones were killed by police. Crump had come back to his home base in Tallahassee to represent Duane Washington, a retired Army veteran and software tester who was permanently injured when he crashed his motorcycle during a 45-vehicle pileup on a Florida highway.

The case drew scant attention outside the local community in the state’s panhandle—at least in the beginning.

A storm moves in

After finishing work on July 24, 2018, Duane Washington put on a light jacket, leather gloves, elbow and knee pads and a full-face helmet before hopping onto his 2008 Aprilia motorcycle to head home.

He turned onto westbound Interstate 10, the route he usually took for the 30-minute commute. As he cruised along I-10, a heavy rainstorm moved in.

Washington’s memory is spotty about what happened next. He remembers traffic slowing down and seeing lots of brake lights as the rain turned into a torrential downpour. Up ahead, a semitrailer truck had jackknifed, triggering a series of crashes behind it, including cars and other trucks. Washington decided to pull over at an underpass to get out of the pounding rain and wait until the storm passed.

A 45-vehicle pileup on Interstate 10 in Florida during a heavy rainstorm in 2018 left motorcyclist Duane Washington critically injured. Photo (c) The Tallahassee Democrat/Joe Rondone - USA Today Network

As he steered left to the median, Washington slammed into the back of a pickup truck that also had pulled over to stop, and he was thrown from his motorcycle.

A woman driving behind Washington saw him crash. “Oh my gosh. This man is dead … I can’t believe I just saw that,” she later recalled saying to herself. She stopped and got out of her car to check on him. “I honestly just prayed for him.”

Other drivers who saw the crash dialed 911 from their cellphones but could not get through, likely because the system was overloaded with callers who had witnessed or were involved in the massive pileup. Authorities already were on the way. Washington was conscious but unable to talk as he lay on the ground. An off-duty paramedic at the scene asked him some questions, which he answered by blinking his eyes. Washington, who was 40 years old at the time, sustained the most serious injuries among at least eight others who were hurt.

Multiple semitrailer trucks were involved in the Florida crash, causing traffic to back up for miles. Photos (c) The Tallahassee Democrat/Joe Rondone - USA Today Network

The Florida Highway Patrol believed the pileup started when a semitrailer truck driver took evasive action to avoid another driver who had slowed down during the rainstorm.

Truck crashes piling up

The number of crashes involving large trucks has been rising during the past decade. In 2019, the latest year for which statistics were available, 118,000 trucks were involved in crashes resulting in injuries, more than double the number of such crashes in 2009. The majority of those injured were in other vehicles. And since 2010, the number of deaths had increased 36% to 5,005 in 2019, with most of those killed riding in other vehicles, according to the National Safety Council.

While the statistics show an increase in the number of truck crashes, they do not indicate what caused them or who was at fault. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Report to Congress on the Large Truck Crash Causation Study, the only such analysis of its kind, examined crashes between 2001 and 2003 that resulted in injury or death. It found that passenger vehicles were the “critical reason” for crashes in 56% of the incidents involving trucks and passenger vehicles.

Whatever the cause, personal injury and wrongful death lawsuits routinely follow such crashes, seeking to ascribe liability and collect damages. And as the number of crashes has increased, so has the size of jury awards and settlements, often resulting in what some lawyers call “nuclear verdicts”—multimillion-dollar damages verdicts significantly higher than expected given the injuries in the case, generally in excess of $10 million.

The upward trend in such verdicts began in September of 2011 when a jury in Cobb County, Georgia, heard a wrongful death case against Landstar Ranger, a Florida-based trucking company. One of its drivers ran an 18-wheeler through a stop sign and plowed into a pickup truck, killing two men and seriously injuring a woman in the back seat. After a two-week trial, the 12-member panel came back with a $40 million verdict.

“The birth of the nuclear verdict was the Landstar case,” says Charles Carr, a longtime defense lawyer for trucking companies. “That was a harbinger of things to come.”

Seeing the possibility of large payouts, plaintiffs attorneys became less inclined to settle cases right away, Carr says. “I’ve lived this stuff. It’s an issue that’s pretty significant, and it’s significant for the transportation industry,” he says.

The American Transportation Research Institute, a not-for-profit research organization for the trucking industry, took notice. In 2020, it published a study that found nearly 300 lawsuits from 2006 to 2019 resulted in jury verdicts over $1 million against trucking companies. Of those cases, 71 ended in verdicts of more than $10 million. In one case, a Georgia jury awarded $280 million to a family that lost five people in a crash. “Over several decades, the trucking industry has become a leading target for litigation,” the report says.

Carr says all trucking companies are now faced with the consequences of these huge verdicts. “Insurance companies are less likely to insure them,” he says. “And excess insurance has become prohibitively expensive. The smaller mom-and-pop carriers won’t be able to survive.”

The report, Understanding the Impact of Nuclear Verdicts on the Trucking Industry, noted, however, that while the size of awards has gone up, nuclear verdicts still represent a small portion of the awards.

Road to recovery

Duane Washington, a single father who was raising three sons, arrived at the hospital in critical condition. The impact of the crash broke both sides of his pelvis away from his spine. His internal organs were smashed, and he suffered from severe colon and urethra damage. He was not expected to live.

Washington endured multiple surgeries to repair the damage to this body. He was hospitalized for six months and faced difficult physical therapy afterward, enduring constant pain. He could not walk without the aid of a specialized crutch.

Duane Washington and two of his sons during better times. Photo courtesy of Duane Washington

Shortly after the crash, Washington’s sister, a family law attorney, recommended he get in touch with Robert Cox, a personal injury lawyer she had worked for while in law school. Cox agreed to take the case and knew just who to call to work with him on it: Ben Crump. Cox and Crump were old friends. Cox had mentored Crump and hired him as a clerk while Crump was in law school—long before he became internationally known for representing the families of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd.

Despite a busy schedule that had him crisscrossing the country, Crump said yes. Representing Washington would be more than a personal injury case to him: He says it was about seeking justice for another Black man whose life mattered. While Crump was traveling, Cox got to work on the case.

In November 2018, about four months after the accident, Cox filed suit in Gadsden County against multiple defendants, including Sinclair Broadcast Group, the company that owned the pickup Washington crashed into; North American Van Lines and the transportation company it contracted with whose truck jackknifed during the pileup; and Top Auto Express, whose car carrier sideswiped and struck multiple vehicles, closing off two lanes of the interstate.

The suit sought unspecified damages for Washington and his children.

Laying out the case

The defendants indicated through court filings that they planned to argue Washington’s own negligence contributed to his crashing into the back of the pickup. The extent of Washington’s negligence, if any, could diminish a potential damages award.

Like other complex civil cases with multiple defendants, this one moved slowly. When COVID-19 hit, the proceedings had to be held remotely. The lawyers continued to move forward preparing for trial—as well as discussing settlement proposals.

One of the defendants, Top Auto Express, declined a settlement proposal for $1 million and pressed forward for a trial. But the company was curiously lagging in its court filings as the weeks and months moved on. Top Auto’s lawyers told the court they were having trouble getting cooperation from their client and asked for an extension to fulfill requests for discovery.

But Cox was running out of patience and asked Judge David Frank to impose sanctions against the Top Auto Express lawyers. Three days later, the lawyers for Top Auto Express asked to withdraw as counsel, citing irreconcilable differences with their client.

The judge granted their request.

After a month passed, it became clear that no other lawyers were going to take the case. The owner of Top Auto Express failed to respond to court summonses, and the judge declared a default judgment against the company.

The court would now have to summon a jury to decide the damages.

Fighting back

Jury awards in personal injury cases like Washington’s have the potential to go high—so high that one defense attorney decided to write a book to help the defense bar fight back against what he sees as a climbing number of outsize verdicts.

“The reality is that nuclear verdicts happen because of excellent plaintiffs lawyers, and the defense has not kept up,” says Robert Tyson, a San Diego-based trial lawyer and author of the self-published book Nuclear Verdicts: Defending Justice for All.

He says plaintiffs lawyers have done so well because they’re willing to discuss strategies with one another. “As defense lawyers, we don’t share information with each other or don’t share much,” he says.

Bob Tyson: “During this pandemic, these truckers were American Heroes trucking food all over our country.” Photo by Luis Gonzalez

Tyson has observed that plaintiffs attorneys are not only adept at eliciting sympathy for their clients but also at building anger against defendants, portraying them as big, bad greedy companies. “Get the jury angry at the defendant—the corporate defendant,” he says.

The trucking industry, Tyson says, is one such target. “The trucking industry is painted in a terrible light by plaintiffs attorneys,” he says, “During this pandemic, these truckers were American heroes trucking food all over our country.”

While researching his book, Tyson interviewed lawyers who told him they believe jurors have become desensitized to large verdict awards. They may have read about or watched news stories of large jury verdicts and see them as normal.

Large awards are typically challenged or become subject to negotiated settlements. According to a recent report in Law.com, appellate lawyers are routinely sitting in during trials to help identify objectionable and emotionally charged statements as well as to preserve issues for appeal.

Elissa Haynes: “Juries are not understanding the true value of money. It’s like Monopoly Money.” Photo by Chris Voith Photography

Elissa Haynes, an appellate attorney for insurance companies and a partner at Drew, Eckl & Farnham in Atlanta, has done just that. “In the insurance defense field, it’s always been difficult to explain to a carrier that they also need an appellate attorney at the table,” she says. “But because of the nuclear verdicts, they recognize the importance of having a second set of eyes.”

Haynes says she can sympathize with those who have been severely and permanently injured in crashes, and she can accept when her clients are found liable. But she says many damage awards have been excessive. “We are seeing a significant portion of verdicts that are out of proportion,” she says. “Juries are not understanding the true value of money. It’s like Monopoly money.”

Jury verdicts should reflect “what’s reasonable and necessary,” she says. “I’ve represented enough mom-and-pop truckers who have had good safety records and have this one accident—and that’s it.”

Rich Pianka, deputy general counsel for the American Trucking Associations, a national federation of trucking associations from all 50 states, says many awards are justified. “Not all large verdicts are nuclear,” Pianka says. “And sometimes large verdicts are appropriate. We’re concerned about inflated awards that are not justifiable.”

Pianka says the trucking industry is seeking to tamp down litigation to make it “less of a jackpot venture” and instead focus on making inju red people whole. “There is a sense that taking money from trucking companies is free money—that their insurance will cover it,” he says. “Of course, that’s not the case. This money doesn’t come out of the sky.”

The trial begins

The damages trial for Duane Washington would be the first held remotely in Gadsden County and presented several challenges, including how to pick a jury that did not exclude those with limited technology skills or access to computers.

“Our first challenge was, ‘How do we get a random pick of jurors?’ We had to agree to provide the technology to people who did not have the technology. And just as important, we had to agree to provide support so that people who have not used Zoom or a similar system would know how to do it,” Cox says. “We were very concerned that we would not have enough jurors.”

The plaintiffs hired a court technology liaison to help jurors with their computers and Zoom applications and covered the cost to provide laptops and mobile hot spots to ensure they had strong wireless connections.

“I think we got a good diverse jury, something that we were very concerned about because we saw that a lot of marginalized people and minorities would not be able to afford it,” Crump says.

As the jury in Duane Washington’s case watched and listened to the proceedings, they learned that Top Auto Express was found negligent by default, and that no lawyers or representatives for the company would be participating in the damages portion of the trial. It would be a one-sided case with just a handful of witnesses, including doctors, members of Washington’s family and Washington himself.

Still, Crump and Cox, both veteran litigators, were in unfamiliar territory arguing to a jury sitting at home watching on computer screens. Winning a substantial verdict would not necessarily be a slam dunk.

Veteran personal injury lawyer Robert Cox knew just who to call to work with him on Duane Washington’s case: his old friend and protege Ben Crump. Photo courtesy of Ben Crump Law

“I was very concerned whether we could connect with the jury,” Cox says. “A lot of us are engaged in a lot of theatrics and a lot of movement that is intended to help with the persuasion. Zoom takes that away. So all you’re hearing is a detached voice in the background talking to a talking head.”

Crump and Washington were in the same rented office across from the courthouse, allowing Crump to conduct a direct examination of his client in person. Both appeared on camera in the same frame so that jurors could watch them interact.

“We thought it would be important for the jury to see the interaction between the lawyer and the witness,” Cox says. “In a typical Zoom setting, you’re not going to see the lawyer. All the jury would see is the face of the witnesses.”

Crump laid out the story of Washington’s life, telling the jury how after the crash, his injured client lamented that he had only been good at two things in his life: being a soldier for the Army and being a dad. He quit the Army, he told Crump, so that he could concentrate on raising his boys.

“I saw a white lady on the jury during Zoom, she put tissues to her eyes when she heard that, and I knew we had connected,” Crump recalls. “And I thought that was so significant about this Zoom experience, that just like in the movies, you can still connect human emotion no matter what.”

Cox watched as Crump deepened that connection. “That was the most powerful thing I’ve ever seen,” Cox says. “We were watching the jurors on the monitor, several of them teared up. It was definitely effective.”

“One of the things that was truly riveting was to watch the human emotion that went through the Zoom computer screen,” Crump says. “I don’t know why we were so surprised. We go to the movies all the time where you have people laughing and crying and going through all kinds of emotion while watching a movie screen.”

An extraordinary win

The six jurors deliberated for about an hour on Zoom, calculating medical expenses, loss of income, loss of financial support for Washington’s children and how much to compensate him for the things he lost in his life that he’ll never have again.

Their decision made it clear that Crump and Cox put on an extraordinary case. They awarded their client $411 million—likely the highest amount ever for such a case.

“It’s an alarming number,” the American Trucking Associations’ Pianka says of the award. “Even if it’s a one-off, it might encourage others to shoot for the moon.”

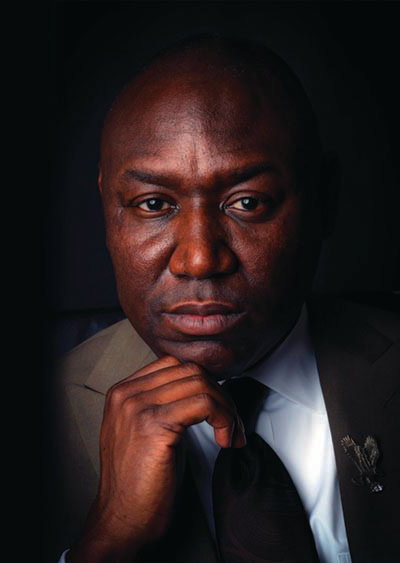

Ben Crump: “The jury showed that this black man’s life matters, that his life experiences matter.” Photo courtesy of Ben Crump Law

Crump says the jury sent a message “that this Black man’s life matters, that his life experiences matter, that his relationships with his children matters. They returned a verdict that I believe spoke to them and rendered full justice to Duane Washington.”

But for Duane Washington, life will never be the same. He’s in constant pain and cannot walk unaided. Before the accident, he used to go swimming, visit amusement parks, play racquetball, volleyball and basketball. He enjoyed going for walks and tossing around a Frisbee. He used to cook but now cannot handle multiple tasks in the kitchen for fear of burning food on the stove.

Because of pending litigation issues with other defendants, Washington’s lawyers declined to make him available for an interview.

Cox says no amount of money could restore his client’s quality of life. “He has lost the ability to do everything you take for granted,” he says. “The size of the verdict relates to Ben’s point about the dignity and value of African American lives.”

Adds Crump: “The injuries Mr. Washington suffered were horrific—not only to himself, but also to his three sons. And I think everyone on that jury understood that loss had occurred due to the negligence of the trucking company.”

Juror Clifford Hill, recently retired as pastor of the Palace African Methodist Episcopal Church in Havana, Florida, watched the trial on his laptop in the church office.

Hill was sympathetic to Washington and the challenges he will face. “This guy has been injured for life, and his family has been disrupted,” he says.

The size of the damages awarded, Hill says, reflected how the jury felt about no one showing up to represent Top Auto Express.

“Somebody should have come to represent the company,” Hill says. “That probably would have reduced the award. The implication was that they had something to hide. The company didn’t take responsibility.”

Cox agrees that the lack of representation hurt Top Auto. “If you’re not going to show up, don’t do it in a case where Ben Crump is the lead lawyer,” he says. “You don’t want to leave Ben Crump alone in front of a jury.”

The registered owner of Top Auto Express could not be reached for comment. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, Top Auto Express’ motor carrier registration is inactive. Four phone numbers associated with the company are no longer in service.

The lawyers who withdrew from the case have since moved on to another firm and did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Washington’s lawyers knew that collecting a $411 million verdict from the now-defunct trucking company would be impossible, and they negotiated a settlement with the insurers for about $1 million.

Eight months after the Top Auto case ended, one of the other defendants in the case, Sinclair Broadcast, went to trial in person at the Gadsden County Courthouse under strict COVID-19 safety protocols that included plastic shields and masks.

Sinclair employed the driver of the pickup into which Washington crashed. The driver had indicated he did not signal when changing lanes and did not put on emergency flashers after stopping. He says he braked abruptly and admitted to being on his cellphone with his wife.

The jury found the company 65% liable in the crash, North American Van Lines 30% liable and Washington 5% liable. At press time, a separate trial to determine damages was scheduled for Oct. 18.

This story was originally published in the October/November 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Costly Collisions: A small-town personal injury case sends a powerful message to the trucking industry.”