Government Work

Penelope Farthing and Matthew Oresman

Photo by Ron Aira

Matthew Oresman faced a most unusual challenge recently: One of his clients, an American corporation that does business in South America, had an employee who was kidnapped. Oresman was thrown into crisis management, researching the law on ransoms and conferring with the Justice and Treasury departments so he could offer appropriate advice.

The employee ultimately was released without a ransom. But the ordeal illustrates the rush and excitement Oresman, 30, an associate at Patton Boggs, gets from a career as a Washington, D.C., lobbyist.

Oresman at first was interested in international law and policy when he landed a job in the Patton Boggs corporate department after law school. He had some policy experience working in U.S.-China relations. But drafting legal memos on esoteric topics didn’t give him a sense of tangible accomplishment, so he gradually began getting assignments in the firm’s governmental affairs department.

“I stumbled into it. I ended up finding the perfect fit,” Oresman says. “You are very rarely doing the same thing twice. You are always on the cutting edge of the law. The problems I get presented with on a daily basis are problems that no one has been presented with before.”

Lawyers are among the most successful lobbyists, a trend that has been growing steadily over the last dozen years or so, experts say. More firms have opened governmental affairs practices to help clients navigate the complexities of Capitol Hill and state capitols.

“We’ve certainly found through the years that the interest in participating in advocacy and government affairs has been on the rise,” says Thomas Susman, the director of the ABA’s Governmental Affairs Office.

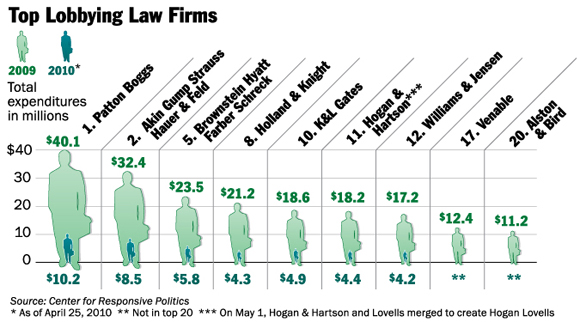

That interest has translated into dollars and manpower—nearly $3.5 billion in 2009 and 13,751 registered, active lobbyists in Washington, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Law firms were well-represented among the top-20 lobbying groups in Washington.

UNDERCOVER JOB

Lobbying is not a field that gets much mention from career counselors or recruiters at law school job fairs. “I’ve never had a student come to me and say, ‘I want to be a lobbyist,’ ” says Marianne Deagle, assistant dean for career services at Loyola University Chicago School of Law. “It’s something they come to after they’ve been practicing a year or two, particularly if they’re working in a state or federal organization.”

Illustration by Adam S. Weiskind

The trip from lawyer to lobbyist often starts with work for a government agency, a congressional committee or a member of Congress. Coupling the skills to draft and read legislation (and bend ears persuasively), many are snatched up by lobbying firms after their stints in government.

“Nobody offers a degree in lobbying and there is no bar exam,” says Patti Jo Baber, executive director of the American League of Lobbyists, a trade association based in Arlington, Va. “If company A works with a good staffer who specializes in appropriations and wants to leave the Hill, that becomes the ideal person for company A to hire.”

Lawyer-lobbyists insist they are providing a valuable service to those who would otherwise have no ability to navigate the complexities of government.

“There’s a lot of space for negotiation in our system,” says Penelope S. Farthing, senior counsel at Patton Boggs in D.C., who represents municipalities and nonprofits. “It is very frankly built to give input of the public.”

Farthing says she and other lawyers at the firm spent “days on end” analyzing the Obama economic stimulus bill for municipalities. “They can’t fly up here every time they need to know something. … I don’t know how they would have done it on their own.”

Susman agrees that lawyers and lobbyists are a good fit.

“A nonlawyer lobbyist needs to have a lawyer handy,” he says, noting that lawyers are well-suited to understanding the implications of legislative language.

So do trade associations seek out lawyers when they’re looking for lobbyists? Their recruiters and members of lobby associations say not necessarily so. They may say they want a former member of Congress, though many legislators are lawyers, recruiters say.

Pamela Kaul is president of the Alexandria, Va.-based executive search firm Association Strategies, which helps corporations, trade associations and nonprofits hire executives. Kaul says her clients are primarily looking for people with a depth of understanding in an industry or, for example, experience on the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee

“Anecdotally, it’s probably correct that maybe more lawyers are getting hired to the world of trade and professional associations,” she says.

“But I don’t know if that’s tar geted or if they just have the skill set.”