50 years later, Freedom of Information Act still chipping away at government's secretive culture

Photograph by Worldwide Hideout

Johnson’s comments at the low-key signing ceremony at the ranch illustrated his mixed feelings about the new law. “I signed this measure with a deep sense of pride that the United States is an open society,” he said. “I have always believed that freedom of information is so vital that only the national security, not the desire of public officials or private citizens, should determine when it must be restricted. At the same time, the welfare of the nation or the rights of individuals may require that some documents not be made available. As long as threats to peace exist, for example, there must be military secrets.”

Johnson’s comments still describe the ongoing tension between the commitment to disclosure of government information to members of the press and public measured against the governmental inclination to withhold information, most often on grounds of national security.

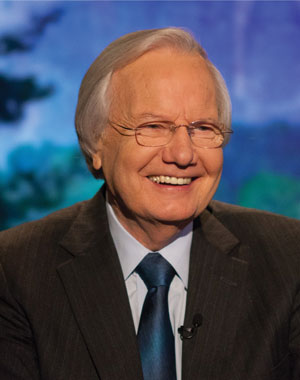

Consternation over FOIA was not confined to the Oval Office. More than a dozen federal agencies actively opposed the bill and testified against it at congressional hearings. But the press and some committed members of Congress actively pushed it to fruition. Even Johnson’s own press secretary, Bill Moyers, encouraged his boss to sign the bill into law.

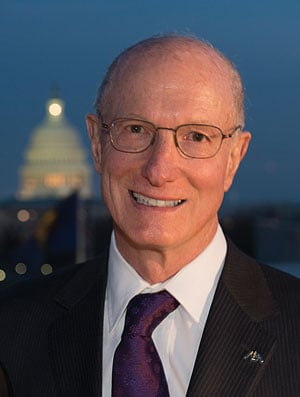

Bill Moyers. Photograph by Dale Moyers.

“Getting FOIA passed was almost as difficult as making it work once it was law,” says Moyers, who left the administration in 1967 for a career in broadcasting and political commentary. “Even LBJ got cold feet; and only at the last minute, pressed by John Moss and his friends in the press, did he turn it around and claim FOIA as his own, even exulting over it. We had to fight for it then, and we have to keep fighting for it 50 years later.”

SHARPER TEETH

The concepts embodied in FOIA were not new when it became law in 1966. Provisions of the act originally were contained in the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, but their teeth weren’t very sharp. Many advocates of more open government were concerned that the APA gave federal agencies more discretion to withhold information rather than disclose it.

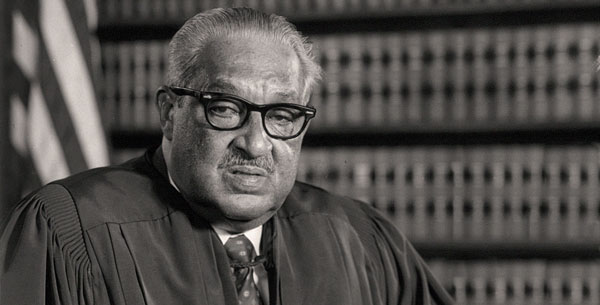

FOIA took those provisions out of the APA to bolster disclosure requirements governing federal agencies, and the law continues to be the leading federal statute providing a mechanism for individuals to request government documents. “The basic purpose of FOIA is to ensure an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors accountable to the governed,” wrote Justice Thurgood Marshall in a dissenting opinion in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1978 decision in NLRB v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co. that the National Labor Relations Board did not have to disclose its witness statements because they were exempt under FOIA.

Open government advocates emphasize the importance of FOIA to a fully functioning constitutional democracy. “I don’t think it is possible to overstate the impact of FOIA on openness in government,” says Jane E. Kirtley, director of the Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. “The FOI Act is an imperfect tool, but as compared to many other countries’ comparable legislation, it is remarkably effective. Without FOIA, we’d be left with the Administrative Procedure Act and not much else. Given the range of regulatory and enforcement activities of the executive branch, it is imperative that the public have a tool that makes it more open and accountable. FOIA is that tool.”

FOIA has allowed reporters and others to uncover government abuses, wasteful government spending and safety hazards. The Sunshine in Government Initiative, a self-described “coalition of media groups committed to promoting policies that ensure the government is accessible, accountable and open,” provides in its online FOIA Files numerous examples of how journalists have used FOIA requests to uncover vital information, such as how the federal government turned down millions of dollars in aid after Hurricane Katrina; how 17,000 bridges have not had up-to-date safety inspections; how there is a serious backlog of disability benefit requests that have been filed by recent veterans from wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; and how the Pentagon has ignored serious waste allegations.

“These and a long list of other such reporting never would have been possible without the FOIA,” says Paul K. McMasters, a longtime advocate for the First Amendment and freedom of information who is the former national ombudsman for the Freedom Forum. “This flow of information transcends annoyances or embarrassments to public officials; it revitalizes and strengthens the working relationship between the government and the citizenry.”

Photograph by Worldwide Hideout

(As a matter of disclosure, this author holds a part-time position with the Freedom Forum as First Amendment ombudsman.)

“The federal Freedom of Information Act stands as one of the essential clauses of the working contract between a government and its citizenry,” says McMasters, who is a past president of the Society of Professional Journalists. “The law assures an informed citizenry that in turn assures a government that can more effectively protect and serve that citizenry. When government officials fail, or refuse, to share with fellow citizens information vital to full and fair participation in the democratic process, however, that fragile contract is shattered. That leaves a government vulnerable to potential corruption and actual incompetence.” FOIA helped change the thinking about how to approach disclosure of information by the government, says Thomas M. Susman, director of the ABA Governmental Affairs Office in Washington, D.C. “Bureaucracies are by their nature secret,” says Susman. “FOIA started to reverse the culture that presumed everything was secret unless it was in the interest of the government to release it.”

THE CRUSADER

Gaining passage of FOIA was no easy thing. It took the herculean efforts of Moss, a Democratic congressman from California, to keep the measure alive for more than a decade. Moss died in 1997.

“It was an all but impossible task that took 12 years, but John Moss was tenacious and he saw it through,” says Michael R. Lemov, author of People’s Warrior: John Moss and the Fight for Freedom of Information and Consumer Rights. “President Johnson thought at one time it was terrible legislation. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower also opposed it. Every federal executive agency opposed it. John Moss is an underappreciated American hero, and he really was the people’s warrior. Without his tenacious and tireless efforts, FOIA would not have been passed until much later.”

Moss made his feelings clear in a speech on Capitol Hill in June 1966, shortly before his bill was passed. “We must remove every barrier to information about—and understanding of—government activities consistent with our security if the American public is to be adequately equipped to fulfill the ever more demanding role of responsible citizenship,” he told his colleagues in the House.

President Lyndon B. Johnson. AP Images.

Moss emphasized three basic changes brought about by his measure. First, the bill required that most government records would be available to “any person” rather than simply to those “properly and directly concerned.” Second, the measure identified discrete categories of exempt records instead of relying on vague phrases like “good cause” or “in the public interest” to control decisions about disclosure. And third, the bill gave a person whose request for a record was denied a right to challenge that denial in federal district court.

“Everyone agrees that Moss was pivotal,” says Michael S. Schudson, a professor at the Columbia Journalism School in New York City and the author of The Rise of the Right to Know. “He was a bulldog on the topic of freedom of information. For over a decade it was the subject he lived and breathed. He was the leader and his staff ran the switchboard connecting journalists, media lawyers and legislators to make FOIA happen.”

During his tenure as speaker of the House of Representatives, Sam Rayburn appointed Moss as chairman of the Special Subcommittee on Government Information. From this position, Moss fumed that the Civil Service Commission was withholding countless documents related to the discharge of employees on the basis of security.

Moss eventually landed a co-sponsor from across the political aisle:

Donald H. Rumsfeld, an Illinois Republican who was a member of the Subcommittee on Foreign Operations and Government Information. Rumsfeld, says Schudson, “was an ardent and outspoken supporter of the legislation that became FOIA. Later, serving as secretary of defense for President George W. Bush, he was far less than a FOIA enthusiast and, in his memoir, wrote very critically of the legislation he had once supported.”

A PUSH FROM THE PRESS

FOIA was not something that sprung from public outcry over the overclassification of government documents. Moss’ primary allies were journalists.”The public did not insist on FOIA,” Schudson says. “FOIA was generated from inside the Beltway without grassroots support. The only supporters—and they worked closely with the Moss committee—were journalists, especially organized associations of journalists like the American Society of Newspaper Editors and the journalism honorary society, Sigma Delta Chi. FOIA emerged from congressional efforts to control a rapidly growing executive branch of government, not from a general public faith in a right to know.”

But FOIA was not a perfect piece of legislation. The law failed to create a culture of openness within many federal agencies. Instead, agencies often stonewalled on requests for information. Significantly, the law contained no meaningful time requirements for agencies to respond to disclosure requests.

Many government agencies broadly interpreted the nine exemptions in FOIA, covering national security, internal agency rules, the so-called statutory exemption, trade secrets, internal agency memos, personal privacy, law enforcement records, bank reports, and oil/gas well data. Some of these exemptions are still broadly interpreted by some government officials, particularly the ones addressing national security, personal privacy and law enforcement records.

Justice Thurgood Marshall. Photographs Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Library of Congress.

In the wake of the Watergate scandal and several court decisions that expansively interpreted several FOIA exemptions, Congress amended the act in 1974. These modifications added time requirements and imposed sanctions when government officials failed to comply. Under the amendments, for instance, agencies now had 10 working days to process FOIA requests.

Citing national security concerns, President Gerald R. Ford vetoed the measure, in part based on legal advice from Antonin Scalia, who was a member of the Office of Legal Counsel. Congress overrode President Ford’s veto.

“The 1974 amendments gave teeth to the law,” says Susman, who was a driving force behind them as chief counsel to the Senate Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure. “Most fundamentally, it made the law much more useful to the people.”

President Harry Truman signs the Administrative Procedure Act in 1946. The concepts embodied in FOIA were part of the APA, but their teeth weren’t very sharp. Photographs Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Library of Congress.

Charles N. Davis, a longtime freedom of information expert and dean of the Henry W. Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia in Athens, says the 1974 amendments “represent the most substantive reforms to the federal act in its history.” “They reflect the tumult of post-Watergate Washington and, of course, had to overcome a presidential veto—a sure sign that they were meaty enough to accomplish something. There were many substantive changes in the 1974 amendments: potential sanctions for ‘arbitrary or capricious’ denials of FOIA requests; uniform agency fees for search and duplication; and time limits in responding to requests. The real controversy arose over the provision calling for in camera review of requested documents by the court to see if documents were in fact properly classified.”

In 1996, Congress passed the Electronic Freedom of Information Act amendments to FOIA. These clarified that electronically stored materials are records within the meaning of FOIA. Under the law, those seeking information under FOIA could request information in “any form or format” if the agency has the ability to reproduce the material in that format.

Many freedom of information experts maintain that governmental openness took a backseat during the Bush presidency, particularly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Nevertheless, in an address to the American Society of Newspaper Editors in 2001, Bush echoed the mixed feelings about the act that go all the way back to Johnson.

“There needs to be a balance when it comes to freedom of information laws,” said Bush. “There’s some things that when I discuss [them] in the privacy of the Oval Office or national security matters that just should not be in the national arena. On the other hand, my administration will cooperate fully with freedom of information requests if it doesn’t jeopardize national security, for example.”

When President Barack Obama took office in 2009, he pledged to provide for a more transparent government than his predecessor. In a memo to federal agencies on his first day in office, Obama wrote that “the Freedom of Information Act should be administered with a clear presumption: In the face of doubt, openness prevails.”

Jane Kirtley. Photograph Courtesy of Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law at the University of Minnesota.

There has been debate, however, about whether the Obama administration has followed through with the spirit of openness and transparency identified in the 2009 memorandum. “My friends involved in the access and transparency world tell me no,” Susman says. “There are probably two reasons for this. First, there is the phenomenon of high expectations and lower realizations. Second, the Justice Department has been a force of restraint on agency disclosure.”

‘PATHWAYS THROUGH THE FOREST’

FOIA experts cite a number of threats to open government in the context of the act. They mention national security, privacy, the general growth in the number of classified documents and public apathy.

Schudson says both secrecy and openness have increased since the 1960s and the exponential growth of the executive branch of government. “The scope of what counts as ‘national security’ only grows,” he says. Susman agrees: “Certainly after 9/11, national security loomed much more important. But many studies have shown that much information withheld on national security grounds would not have harmed national security if disclosed.”

Kirtley says the national security exemption in FOIA remains an omnipresent threat to open government. “Trying to pry loose anything that the intelligence community considers to implicate national security is almost impossible,” she says. “This is not a new problem, but I think many of us had hoped it would fade to some degree after the end of the Cold War. Unfortunately, the war on terrorism has revitalized it. Since 9/11, of course, national security in all its permutations has taken on a life of its own. The development of the concept of a sensitive, but not classified, exemption at least in practice has made it very difficult to get access to a lot of records using FOIA.”

Kirtley cites privacy as another significant concern. “Many years ago, I said that privacy was going to be the biggest obstacle to successful use of FOIA,” she says. “I think that is still the case. The concept of FOIA privacy has been expanded and in my opinion distorted.” She cites National Archives and Records Administration v. Favish, a 2004 decision in which the Supreme Court broadly interpreted the personal privacy exemption in FOIA to include a right of familial privacy or survivor privacy.

Rep. John Moss accused government officials of misusing labels such as “secret” and “classified” to withhold information from the public. AP Photo

“The number of classified documents grows, too,” Schudson says. “At the same time, the Congress and the public have more tools for making government transparent than ever before. Picture a growing forest of secrets but also a growing number of pathways through the forest so that the keepers of secrets never know when someone might be walking his or her way through one of these growing number of and increasingly popular forest pathways.”

Davis sums up the primary threat to freedom of information in one word: “apathy. The less involved people are in the functioning of government, the easier it is for governments to operate in secrecy. The diminution of the press is a massive threat to open, honest government. Where in many cities you had constant vigilance in the form of beat reporters on city and county governments, the number of boots on the ground is lower than ever; and as the ranks of reporters shrink, the sheer number of eyeballs trained on these lower levels of government—city councils, county commissions, boards of education and the numerous other institutions of local governance—grows lower and lower, and many government institutions across the country now are operating without regular attendance by the press. This terrifies me.”

But while there are many threats to open government and the principle of transparency, people also are using FOIA in record numbers. The Justice Department’s Office of Information Policy notes there were a record number of FOIA requests made in 2015. “These numbers are good news, but

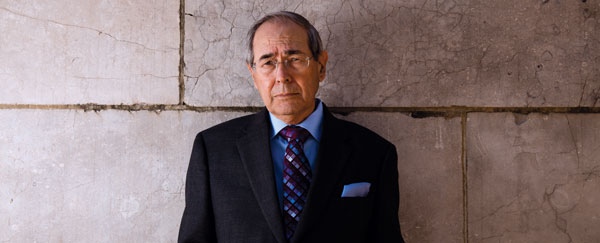

Thomas Susman, a chief force behind the 1974 amendments, says they “made the law much more useful to the people.” Photograph by Mitch Higgins.

I worry about the long-haul costs of litigating denied FOIA requests in an era when the budgets of both mainstream news organizations and government watchdog organizations are strapped,” says Clay Calvert, director of the Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project at the College of Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida in Gainesville. “It’s all fine and dandy to see FOIA still standing at the half-century mark with record-breaking numbers of requests, but meaningless in practice if the financial resources just aren’t there to fight the time-consuming battles when those requests are denied.”

Some current members of Congress have committed to improving the Freedom of Information Act. For several years, Sens. John Cornyn, R-Texas, and Patrick J. Leahy, D-Vt., have introduced the FOIA Improve-ment Act. In February, they introduced their latest version of the bill.

The measure would require federal agencies to post on their websites documents sought in at least three prior FOIA requests. The bill also would codify President Obama’s memorandum of openness by establishing a default presumption of openness. Federal agencies could only deny a request under one of the law’s nine exemptions if they could reasonably foresee that disclosure of the information would harm the interests protected by any of the exemptions, and they would have to explain their conclusions to those requesting disclosure.

“I strongly support this piece of legislation,” says Susman. “It has many positive improvements to FOIA. The real strength of this bill is its grant of authority to the Office of Government Information Services.” Under the FOIA Improvement Act, OGIS would mediate disputes between those with FOIA requests and federal agencies.

“The federal Freedom of Information Act stands as one of the essential clauses of the working contract between a government and its citizenry.” —Paul McMasters. Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

The Senate passed the measure in March. A bill is pending in the House, where passage was uncertain as of press time in early June.

“Our democracy is built upon the premise that our government should not operate in secret,” Leahy says. ”Fifty years ago, Congress confirmed this by passing the Freedom of Information Act, a landmark law which has brought sunshine into the halls of power and made the government more accountable to the people. As we celebrate FOIA, we must also recommit ourselves to improving it. I cannot think of a better birthday present for FOIA’s golden year than Congress enacting the Senate’s bipartisan FOIA Improvement Act to strengthen this treasured law and update it for the digital age.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Sharing Secrets: Despite resistance from presidents and bureaucrats, the Freedom of Information Act continues to be the primary tool for getting information from the federal government 50 years after its passage.”

David L. Hudson Jr., a regular contributor to the ABA Journal, serves as the ombudsman for the Newseum Institute's First Amendment Center.