1955-1964: Civil rights struggle gains momentum

Rosa Parks is arrested for violating the segregation law in Montgomery, Alabama. AP Photo

In 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court received a case that followed logically from its ruling a year earlier in Brown v. Board of Education that separate public schools for races are “inherently unequal.” Naim v. Naim involved a Virginia miscegenation law that negated the marriage of a Chinese man and a white woman, and the justices could snatch another dagger from Jim Crow.

But the court declined the matter because it might stoke the backlash underway, largely in the South, against Brown’s edict. Twelve years later it would overturn the Virginia law against interracial marriage. Much happened in the interim, and much didn’t.

Brown launched a civil rights revolution, driven as much by peaceful protests and passive resistance as by law, which was flouted routinely.

In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white person and was convicted of violating Montgomery, Alabama’s segregation law. Blacks boycotted the bus system for 13 months, until the Supreme Court ruled such segregation was unconstitutional in another case, Browder v. Gayle.

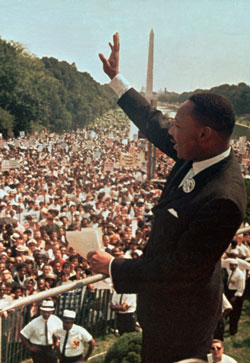

Photo of Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington by AP Photo.

The boycott’s 27-year-old leader, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was catapulted into the national spotlight.

Legislation and judicial rulings only seemed to fan the flames of social unrest. In 1957, Arkansas’ governor used the National Guard to keep black students from enrolling in Little Rock’s Central High School. President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalized those troops, sent them home and brought in part of an Army airborne division to facilitate desegregation. That story played out elsewhere, dramatically so at the universities of Alabama and Mississippi.

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 ended up a weak shell of itself, though it did create what became the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. Another Civil Rights Act iteration, in 1960, added little.

A 1960 sit-in by black college students at a Woolworth’s whites-only lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, caught on throughout the South. The retailer and other chain stores ended such policy. Heady accomplishments were subdued when Freedom Riders—groups of mostly college students—set out together in 1961 on buses through the South, challenging noncompliance with desegregation law. Abetted by the Montgomery police, a mob savagely beat some with baseball bats, pipes and chains—a scene reprised elsewhere.

King’s willingness to face the mobs and take personal risk became a galvanizing force, solidified by his “I Have a Dream” speech at 1963’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Photo of Lyndon Johnson by AP Photo

In 1964, Freedom Summer activists went to Mississippi to challenge voter suppression and register black voters. Many were beaten by white mobs. In June, three activists—two white and one black—were murdered by Ku Klux Klansmen. President Lyndon B. Johnson leveraged the public revulsion to push through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which asserted the force its predecessors lacked. The new act explicitly prohibited discrimination by race, sex, national origin or religion in schools, workplaces, public accommodations and businesses. And it had teeth: The Justice Department could sue for enforcement, and federal funds could be withheld for the same reason.

“It showed the South that the federal government meant business,” says Richard Delgado of the University of Alabama School of Law. “In its way, it was as important as Brown v. Board.”

But discrimination didn’t end; it took new and sometimes disguised forms. Today, for example, there are claims of voter suppression based on the premise of preventing voter fraud. A University of Delaware study showed whites tend to support voter ID laws when a photo of a black person voting accompanies the survey question.

In 2013, the high court took its ax to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a pillar of the civil rights movement, which declared that states and municipalities with a history of discrimination must be “precleared” by the Justice Department or a federal court before they change their voting laws.

In Shelby County v. Holder, the court shot down Section 4, which designates the precleared areas. “Things have changed dramatically” in the South, wrote Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. The decades-old coverage formula was based on “obsolete statistics” and therefore violates the Constitution, he wrote.

As a result, Texas and other Section 4 states have re-implemented their voter ID laws. Warned Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in dissent, striking down that section may permit a “return to old ways.”

A Freedom Rider bus goes up in flames in 1961. AP Photo

100 Years of Law |

|

| « 1945-1954: Footnote 4 | 1965-1974: Watergate and the rise of legal ethics » |