Oct. 29, 1929: The Great Stock Market Crash shakes the nation

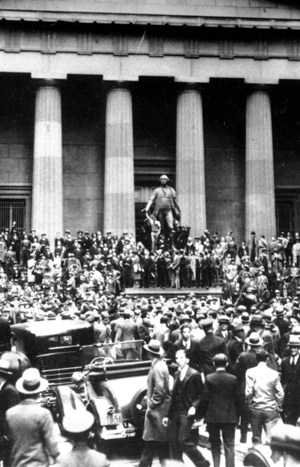

Crowds panic in the Wall Street district of Manhattan due to heavy trading on the stock market in 1929. AP Photo.

On Tuesday, Oct. 29, 1929, as much as $9 billion was lost on a volume of more than 16 million shares on the New York Stock Exchange alone. So much was traded so quickly that hundreds of extra runners had to be recruited from nearby telegraph offices. Stock tickers ran more than two hours behind the trades they were reporting. Similar turmoil was reported by the dozens of exchanges operating in cities, including Boston, Chicago, Montreal and San Francisco. So abject were the losses, so disarrayed were the overloaded markets that a final tally of the day’s disaster was ultimately deemed irrelevant.

Regulation of the markets was nonexistent as a matter of bipartisan policy, so there was no role for a government response. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York met for six hours and elected to do nothing. So at noon, as the markets spiraled downward, a group of bankers met at the offices of J.P. Morgan. In the midst of the massive liquidation, they hoped to stimulate stock purchases by lowering margins required for brokerage loans. “There is plenty of money and it will be loaned freely,” they announced in a statement. A glimmer of hope came in the form of a brief rally in the last 15 minutes of trading on news that U.S. Steel and American Can were raising dividends by $1.

The crash was more of a surprise than it should have been. On March 25 and throughout the summer, the market endured brief panics; they were corrected by more vigorous trading. Instead of being forewarned by the volatility, speculators seemed to decide that stock prices would rise perpetually as long as they continued to buy. The few who voiced fear of a crash were derided as fools.

Thin hope for a market correction seemed justified when the market rebounded lightly on Wednesday and again on Thursday. On Friday and Saturday, the NYSE closed to balance accounts and allow exhausted employees to rest. But on Monday the market declined, and by Tuesday resignation had set in. Massive margin calls made the rich suddenly destitute. Banks closed. Credit tightened. Businesses shuttered. Unemployment swelled. Day after day, month after month, the markets continued a steady downward roll. Between September 1929 and July 1932, the value of stocks on the NYSE alone had dropped more than 80 percent—a loss in excess of $74 billion.

Ferdinand Pecora. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Prompted by the 1932 elections, Congress began enacting a regulatory framework to protect investors and depositors. The Glass-Steagall Act (the Banking Act of 1933) created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. as a safety net for bank depositors. But it also prohibited banks from trading on their own account. The importance of Glass-Steagall was underscored in June 1934 by the Pecora commission. Congress appointed Ferdinand Pecora, a former prosecutor with a reputation for integrity, to investigate the events of Black Tuesday. In a series of public hearings, the titans of business and banking were confronted—in sometimes lurid detail—with the recklessness of their decision-making. The abuses filled 421 pages of Pecora’s report.

Ultimately, Pecora revealed, the culprit was not just stock speculation but also the daisy chain of unrestrained borrowing behind it. Speculators invested on margin with brokers. Brokers, in turn, borrowed from banks to buy stocks for their clients. The bank loans to brokers were backed by the bank’s own deposits, or loans from the Federal Reserve. With cash received from stock issues, corporations began playing the market along with busboys and housewives. And as long as prices were rising, wealth seemed an entitlement. It was a popular delusion of epic proportions.

“If there must be madness,” mused economist John Kenneth Galbraith, “something may be said for having it on a heroic scale.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Great Crash Shakes the Nation: Given the sprawl of the disaster, the optimism expressed on Wall Street seemed delusional.”