Features

1925-1934: On Trial: Science v. religion

(Photo of John Thomas Scopes by AP Photo)

Scopes was indicted for violating a state law that specifically forbade public schools from teaching Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. In the press, the trial was styled as a confrontation between free speech and the Bible and, not incidentally, a contest between William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow, two of the most gifted rhetoricians of their time. But at its heart was a show trial in nearly every sense of the word.

In March 1925, Tennessee Gov. Austin Peay signed into law the Butler Act. Named for a Tennessee farmer and state legislator, the law reflected a belief held by fundamentalist Christians that Darwin's far-reaching conclusions about the development of life on Earth undermined the moral force of biblical truth. The law made it a criminal act for any publicly funded school, including universities, to teach evolution, or any theory "that denies the story of the divine creation of man as taught in the Bible."

Barely a month later, the American Civil Liberties Union began soliciting volunteers to test the new Tennessee law. Sensing that a trial would bring money and attention to their decaying burg, a group of Dayton businessmen recruited Scopes, a football coach and part-time biology teacher, for the ACLU.

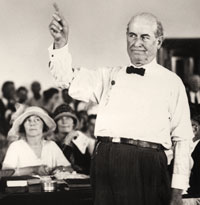

Photo of William Jennings Bryan at the Scopes trial by AP Photo

Though the local prosecutor agreed to pursue a case against Scopes, Dayton elders found star power in Bryan and Darrow. Bryan, 65, was a three-time Democratic presidential candidate and secretary of state under President Woodrow Wilson. He was a devout Presbyterian, a staunch Populist, a steadfast Prohibitionist and an outspoken anti-evolutionist. Darrow was an avowed atheist, a director of the ACLU and the nation's most celebrated criminal attorney. At 68, Darrow seemed the perfect foil for Bryan.

There was much more at play in the case than God versus Darwin. The biblical implications of Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, had already been accom-modated by mainstream religion. Darwin's notion of "survival of the fittest," co-opted as a capitalist moral value by so-called social Darwinists, was as much an affront to Bryan's Populist leanings as to his biblical literalism.

In the midst of the Roaring '20s, however, America was poised between wars and extremes. The stock market was ginning money on its way to the Great Crash. Prohibition, though built on moral probity, was instead creating criminal empires built on political corruption and bathtub gin. America's powerful rural politics were yielding to big cities and an urban sophistication with white-collar employment, low-cost automobiles, birth control and jazz—and the backlash could be heard full-throated in nativism, anti-Bolshevism, radio evangelism and a re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan.

Photo of Clarence Darrow at the trial by AP Photo

Though the trial was intended by both sides to yield a guilty (and appealable) verdict, it still proved sensational. When Bryan agreed to testify as an expert on the Bible, so many spectators showed up that the proceedings were moved outside. Bryan's faith proved no match for Darrow's demanding rationalism. Darrow wondered aloud whether Bryan had questioned anything about the Bible.

"No, sir, I have been so well-satisfied with the Christian religion that I have spent no time trying to find arguments against it," Bryan replied, to growing guffaws. "Were you afraid you might find some?" countered Darrow. Said Bryan: "No, sir. ... I have all the information I want to live by and to die by."

On its eighth day, the Scopes "monkey trial," as it became known, ended abruptly; to ensure a guilty verdict, Scopes entered a plea. But a state appeals court overturned the $100 fine the judge imposed on Scopes. With no grounds for appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Tennessee law remained in effect until it was repealed in 1967.

Bryan, who died five days after the end of the trial, never had the chance to redeem his badly battered reputation, but the debate over biblical literalism has endured over the 90 years since. In 2005, a Pennsylvania school district was permanently barred by a federal court from teaching an alternative to evolution known as intelligent design, and the tension between faith and science continues in the public square.

The Rhea County courthouse couldn't hold all of the 1,000-plus spectators, so the proceedings were moved outside. AP Photo

100 Years of Law | |

| « 1915-1924: Wilson, women and war | 1935-1944: A New Deal » |