May 22, 1856: Abolitionist beaten senseless on Senate floor

Photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On the afternoon of May 22, 1856, Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner was sitting at his desk in the U.S. Senate chambers when a large, nearly apparitional figure appeared behind him. A startled Sumner turned to look when he was struck in the head with the handle of a gutta-percha walking stick.

His seat and desk bolted to the floor, Sumner was unable to right himself as the cane struck again and again—as many as 30 times before the attacker was finally persuaded to pull away from his blood-spattered victim.

As the attack ended, the assailant bent over, casually plucking up the crested gold handle that lay among the splintered remains of the cane on the Capitol floor.

Sumner’s assailant was Preston Brooks, a House member from South Carolina—a Democrat with a reputation for violence. Brooks had taken offense to insults sallied against his distant cousin, Sen. Andrew Butler of South Carolina, in a five-hour speech delivered earlier in the week from the Senate floor.

Several onlookers trying to intercede were held back by Brooks’ supporters. Brooks left the floor unmolested but later presented himself to authorities and agreed to pay a $300 fine.

Reaction to the attack was provincial and complicated. Despite nearly killing a defenseless man, Brooks was hailed as a hero in the South. In the North, Sumner was characterized as a martyr. The muted official response reflected Congress’ inability to agree on anything when it came to slavery. A hastily convened Senate select committee concluded the obvious: Brooks did indeed “assault [Sumner] with considerable violence,” but no Senate rules were available to punish him. Although the House failed to pass a resolution expelling the congressman, Brooks resigned.

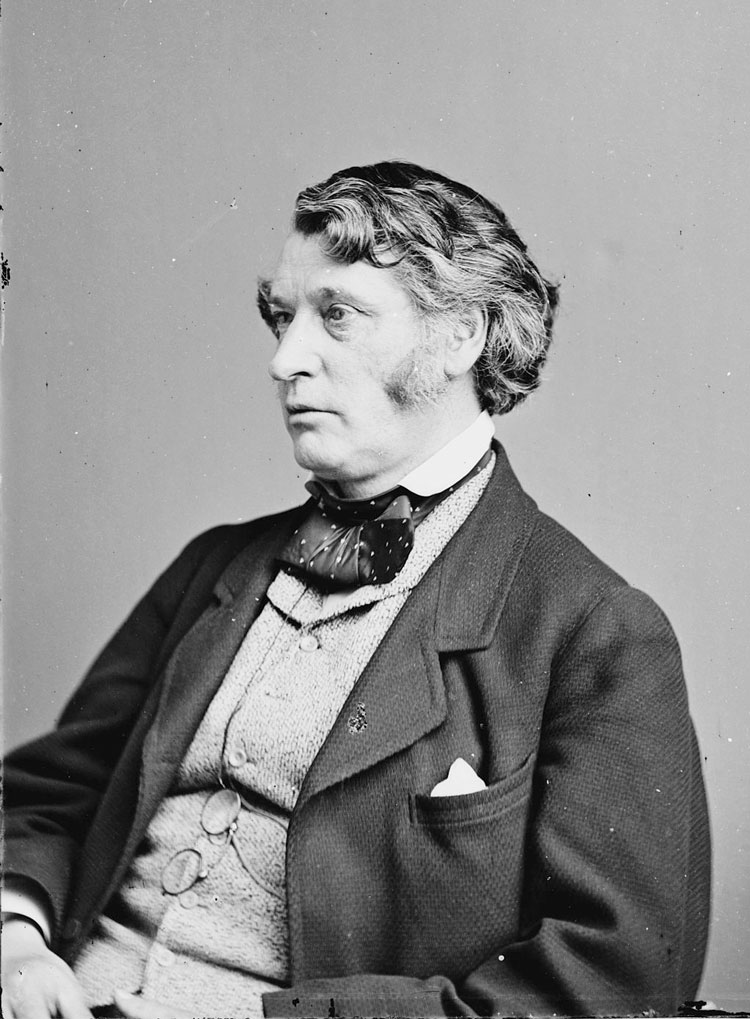

Photo of Sen. Charles Sumner courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Brooks returned home unrepentant. He later wrote to his brother: “Every lick went where I intended. For about the first five or six licks, he offered to make fight. But I plied him so rapidly that he did not touch me. Towards the last, he bellowed like a calf.”

In the North, Sumner was not universally popular. Those who shared his view were sometimes uncomfortable with his strident rhetoric. He wasn’t simply anti-slavery but a determined enemy of racial laws. For that, he was condemned by Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois as a champion for “the cause of niggerism.”

Although Brooks envisioned himself as chivalrous (his need for the walking stick grew from one of two earlier duels), he saw Sumner as a race and class traitor unworthy of a conflict of equals, deserving only the kind of beating a master might deliver to an unruly slave. Sumner viewed those such as Brooks and Butler as brutish, pretentious purveyors of a culture whose sole source of existence was perpetual violence.

That cultural chasm grew deeper as the territories of Kansas and Nebraska were settled, sparking a struggle for their future as slave states or free states. Sumner’s newly founded Republican Party wished to contain slavery in states where it already existed or eradicate it completely. Democrats wanted to let the new states decide for themselves.

The speech to which Brooks took offense, “The Crime Against Kansas,” denounced the role Butler and Douglas had played in the compromise that led to ongoing violence between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers in the territory. The day before the Sumner assault, pro-slavery raiders looted the anti-slavery township of Lawrence. And three days after the caning, abolitionist John Brown led a raid that killed five pro-slavery residents of Pottawatomie Creek.

Brooks was re-elected to Congress a few months after his summer resignation. He died in January 1857 at age 37. Sumner returned to the Senate after 18 months and served until his death in 1874. The violence reached a crescendo during the Civil War, but the chasm between their cultures continues to this day.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.