100 innovations in law

Shutterstock.com

People tend to think of the law as slow-moving, immutable and disconnected from daily life. And lawyers have a reputation of being cautious and resistant to change. But in fact, when technology or sweeping changes are necessary to better serve their clients, improve access to justice or simply make their work easier, lawyers can be pretty progressive.

While fundamental change can take decades, in the past 100 years legal professionals have eagerly adopted technological innovations, streamlined the law and launched new practice areas that were unimaginable just a century ago. The innovation of written laws dates to 1750 B.C., but many of the most important innovations in the law have come in just the last century. Here is a list of 100 technological, intellectual and practical innovations that have fundamentally changed the way law is practiced.

Shutterstock.com

INNOVATIONS IN THE COURTROOM

The oldest known shorthand services were offered in 63 B.C. by one Marcus Tullius Tiro. And in 1913 the stenotype machine made it possible for trained professionals to make a verbatim record. But in 1944, Public Law No. 222 launched the creation of a court reporters system in the U.S. district courts, setting the stage for lawyers (on television and in the real world) to dramatically turn to the court reporter and ask for a pivotal piece of testimony to be read back.

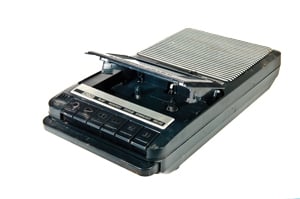

Similarly, recorded depositions changed the litigator’s relationship to witness testimony. The change began with the advent of electrical recording and amplification in the 1920s. In today’s global economy, getting all the relevant witnesses and experts in one place for a legal proceeding is often impossible, making recorded testimony essential.

Video depositions were a controversial innovation when they first appeared in the 1970s, with fears of possible grandstanding, trick questions designed to inspire anger or other forms of manipulation arising as they can when cameras enter the discussion. But since the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were amended in 1970 to allow nonstenographic ways of recording depositions, video depositions have become the way testimony is delivered in many matters.

By the early 2000s, deposition-transcript software became an essential tool for preparing deposition summaries, especially when working with the ubiquitous video depositions. A 1946 federal law expressly banned electronic broadcasting of criminal court proceedings. But in July 1991, a pilot program began in two U.S. appellate courts and six U.S. district courts. The pilot did not succeed in convincing the U.S. Judicial Conference to support cameras in federal courts, though a second pilot, for civil proceedings only, was put in place in June 2011.

With the rise of Court TV (now TruTV) in 1991 and, more recently, the emergence of social media, the public has come to expect instant, unvarnished access to state court proceedings as they happen. In the late 1980s, electronic terminals for e-filing documents first appeared in federal courts, moving online in the 2000s, before e-filing became mandatory in many jurisdictions.

Shutterstock.com

EVIDENCE IN THE COURTROOM

All lawyers want their audience to hang on to every word of their carefully prepared statements. Unfortunately, science shows that immediately after a 10-minute presentation, listeners forget half of what is said. But a truly effective audiovisual presentation increases retention by 45 percent. Presentation software such as Microsoft’s PowerPoint (1990) helped. Now 3D animation, video and medical imaging technology are essential parts of many litigators’ toolkits.

Geolocation technology was opened to civilian use in 2000, allowing Internet service providers to determine where a subscriber is by tracking the user’s Internet protocol address. Law enforcement can now use it to track almost anyone; courts use it to resolve jurisdictional disputes, and attorneys have subpoenaed the information in countless cases. Unreliable witnesses are certainly not a new innovation. But the science that demonstrates just how unreliable eyewitness testimony can be is relatively new, helping to keep countless citizens from being unjustly sent to prison based on one witness’s testimony. Studies considering the reliability of child witnesses were published in the mid-1980s.

Recorded interrogations finally made it less likely that police can coerce or abuse suspects during interrogations—and similarly protect police accused unjustly of misconduct. Jurisdictions began requiring recorded interrogations at the beginning of this century after high-profile cases like New York City’s Central Park Jogger trial of 1990 were upended, lending credence to the defendants’ claims of coerced confessions. The DNA evidence and perpetrator’s confession that freed the five defendants came 12 years after the first convictions.

The smartphone camera, introduced in 2000 (there is some debate whether it first came out in South Korea or Japan), has put law enforcement in a new and often unflattering light. The death of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, resulting from an encounter with police and recorded by a bystander in 2014, stirred a hornet’s nest of racial protest, questioning of police tactics and some public doubt about the use of grand juries when one voted not to indict the police officer involved.

And now an ongoing movement will likely wire more police with body cameras—in addition to car-mounted police cameras—providing more protections to suspects as well as police officers. Perhaps this effort can be traced to those ride-along episodes of Cops, the reality TV series that premiered in March 1981.

Shutterstock.com

EVIDENTIARY INNOVATIONS

Over the past 100 years, forensic evidence has been one area of law in continual flux. Many types of evidence have come into vogue, only later to be discredited, but the field is continually evolving and improving. For example, before DNA analysis was invented, blood typing first appeared in the 1920s to narrow the field of suspects in a matter by blood type, or to tie a child and alleged parent, which led to …More accurate genetic paternity testing in the 1960s, providing more than 80 percent accuracy rates. Those rates have improved to 99.99 percent accuracy in modern times, and it saved the career of Maury Povich, daytime TV’s purveyor of baby-daddy DNA tests. As early as the 1980s, digital forensic investigations were able to recover incriminating emails in the Iran-Contra investigations. Today, certified forensic examiners use specialized software and tools to collect, analyze and review digital evidence in a forensically accurate format. Most famously, the BTK serial killer was caught through evidence found on a computer disk.

Fire and explosion analysis has been facing court challenges, especially since the National Fire Protection Association issued a 1992 guide emphasizing scientific methods of analysis rather than relying on firefighter experience. Firearm and tool-mark identification is one of the oldest forensic technologies, but the science came into maturity in the 1920s when comparison microscopes and other advances made the practice more scientifically precise.

As the war on drugs took off in the early 1970s, gas chromatography (with modern techniques developed in 1950) and mass spectrometry (with modern techniques dating back to 1918 and 1919) were used to identify controlled substances in support of drug cases.

And in 1985, national guidelines from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration made accident reconstruction into a more rigorous practice area.

The granddaddy of all forensic tools, fingerprinting, dates back to around 200 B.C. in China. But in the 1930s, criminal investigators discovered latent prints could be left on fabrics, including the inside of gloves. The FBI’s Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System, a national register of fingerprints, was launched on July 28, 1999, and revolutionized crime fighting, becoming a most important tool—until the innovation that follows this one.

Perhaps no development in criminal law has been more dramatic or transformative than DNA evidence. DNA fingerprinting is now nearly unassailable and incontrovertible as evidence in court; and thousands of Americans wrongly convicted of crimes have been set free because of new DNA analysis and matching. DNA evidence helped inspire the creation of DNA databases. In the late 1980s, the federal government laid the groundwork for the Combined DNA Index System or CODIS, a system of national, state and local databases for storing and exchanging DNA profiles.

And since 1996, mitochondrial DNA has provided forensic scientists with a valuable tool for determining the source of DNA recovered from damaged, degraded or very small biological samples. But it was expert scientific witnesses who made all of that innovative evidence admissible.

The Daubert standard, formed through three 1990s U.S. Supreme Court cases, established a rule of evidence to determine whether expert testimony is admissible.

Shutterstock.com

COMPUTERS TAKE OVER

The start of the law firm computer revolution in law began in the early 1970s when Wang introduced word processing computers, which became the center of law firms’ word processing departments.

Because a lawyer’s work is done in words, desktop word processing revolutionized legal work practices. The days of dictating letters, using dictation devices, or relying on clerks or typing pools have given way to an individual working alone at a computer. Programs such as WordPerfect (from 1980) gave way to Microsoft Word (introduced in 1983). And now Google Docs (available in 2007) with collaborative online editing tools is edging into the lawyer’s toolkit.

In the 1980s, law firms were among the most enthusiastic users of document management software, which made it possible for legal teams to instantly view any document or email associated with a specific client, matter or project.

Adobe’s portable document format became an open standard in 2008, which meant no one company controlled the format. And once the legal profession dis-covered the PDF can be cleansed of some of that annoying metadata that can betray secrets—and can be locked down so it can’t be edited—it became the de facto standard for e-filing and legal document processing around the globe.

More than 40 years ago, Mead Data Central introduced Lexis, offering digitized legal research through electronic copies of Ohio and New York legal codes and cases. That action pushed legal research from the world of leather-bound books to clumsy computer terminals, then to CD-ROMs, and now to the Internet.

The next wave in legal research may already be here: Google Scholar went beta in 2004, making hundreds of millions of cases, research articles and filings easily searchable and free.

Followed by laptops becoming powerful and functional in the late 1980s and smartphones gaining acceptance around 2006 … And then the 2010 iPad and similar tablet devices. According to the ABA Legal Technology Survey Report, within three years of introduction, more than half of all attorneys had adopted mobile devices and tablets to supercharge their practice.

The virtual law firm—an office with no mahogany-walled waiting room, no expensive downtown location and no expensive overhead? Well, how about ditching the office altogether and using technology to communicate, share information and service clients? That’s the idea behind the rise of the virtual law firm, pioneered by people like Stephanie Kimbro, who has provided online legal services for the better part of a decade since getting a law degree in 2003.

Many law firms claim to be paperless, but in reality paper documents remain a part of any practice. Still, in a digital age, leaving paper processes behind and creating a digital law firm is a competitive advantage. In 2006 after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans attorney and blogger Ernest Svenson quit his partnership at a law firm to start a low-overhead, paperless solo practice.

Personal computers were useful tools for man-aging evidence, documents or deposition transcripts. In the 1980s, networked databases like Concordance and Summation made it possible to index and archive complex and massive litigation matters that would have swamped earlier generations of lawyers.

CRIME-STOPPING BEFORE CRIME

In 1994, New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton introduced a data-driven law enforcement management model called CompStat. Depending on your point of view, CompStat is credited with decreasing crime and increasing quality of life in many cities, as well as making police forces less humane and less responsive to their communities.

Regardless of your opinion of CompStat, the next wave of computerized policing is already here—predictive policing, first explored in 2008 by Los Angeles Police Chief William Bratton—yeah, the same guy. This technology uses computer algorithms to identify patterns in criminal activity and position police to prevent and disrupt illegal activity.

Shutterstock.com

EVOLVING PRACTICES

The Supreme Court’s 1977 decision in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona invalidated the longtime ban on lawyer advertising on First Amendment grounds. It was also the opening shot that set off the competitive war in our profession. The day after the decision was published, Jacoby & Meyers published its first law firm newspaper ad.

Following the path of most advertisers, two months later, the first television ad for a law firm was placed in 1977 …And then firms began playing their ads on video-sharing sites such as YouTube, brought online in February 2005. Web-based video outlets made online video available to anyone with a camera. Many lawyers still make their living off referrals, but if your firm is not on TV, social media or billboards, you may not be bringing in new clients you could have.

According to blogger and ABA Journal columnist Bob Ambrogi, the first law firm website was built for Venable (then Venable, Baetjer, Howard & Civiletti) and launched in March 1994. On top of a website, a blog—a format that may have begun in 1983 but didn’t get the moniker until the 1990s—is now vital to marketing many practices. Thanks to the blog, any law firm can easily publish commentary and research for potential clients to find via search engine.

This may surprise many lawyers working today, but the billable hour has not always been the standard for charging for legal work. Until the 1975 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar, fees were decided by discussions between a lawyer and a client based on a county bar association’s minimum fee schedule. Goldfarb and the Federal Trade Commission killed the minimum fee schedule, and today attorneys bill between 1,700 and 2,300 hours annually.

Then there’s the dark side of the billable hour, Skaddenomics. In the 1990s, Skaddenomics became code for billing clients for expenses like long-distance calls—or even luxury hotels. Though the name was inspired by the firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, the practices are common across the legal field.

In 2004, Tyco International invited law firms to craft new and different models for its litigation work. That may have been a response to questionable billing practices; it was certainly part of the business philosophy of cutting costs. And it opened the discussion of alternative billing methods—from flat fees to sliding scales to incentives and punishments—that continues today as it slowly grows in use.

Paralegals first appeared in the 1960s as the ABA and other organizations pushed for more trained nonlawyers to provide cost-effective legal services. Now there are more than 200,000 in the U.S. helping draft documents, do legal research and manage cases. A couple of states are pushing further, allowing nonlawyers to handle certain legal matters that were reserved for lawyers. This year Washington state has begun a limited license legal technician program that will let paralegals with extra training handle certain family-law cases.

ACCELERATING THE PRACTICE OF LAW

As the wireless fax (first used to transmit a picture of Calvin Coolidge in 1924) fades from the legal landscape, it’s difficult to remember how disruptive the technology was. Before the facsimile machine, courts padded all deadlines with at least a three-day delay to allow for mailing documents and contracts. By the 1980s, contracts, filings and briefs suddenly appeared on a lawyer’s desk in minutes. John Quincy Adams considered legal tasks like copying legal codes to be “drudgery, which … does not carry its reward with it.” If only he could have waited 200 years for modern photocopiers (1959). Ditto image scanners attached to computers (1957).

Networking law firms became necessary because computers did not originally connect to one another. The local area network was introduced in the 1980s. A LAN connects multiple PCs to save files to a network drive or share a single printer. America’s first Internet service providers sprang up in various locations in 1989. Let the professional disruption begin.

Perhaps no one knows who sent the first boilerplate email disclaimer, though its ancestor appeared in the cover sheets of legal faxes. But whoever it was who wrote that big block of text at the bottom of nearly every attorney’s email claiming the contents of the message are privileged and confidential helped make email systems (invented by Ray Tomlinson in 1971) an accepted and essential communications tool for law professionals.

Shutterstock.com

COMPUTERS CAUSE CHALLENGES, TOO

The volume of electronic data that is discoverable for litigation is hard to comprehend. Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer lamented at an e-discovery conference that “if it really costs millions to do [e-discovery], then you’re going to drive out of the litigation system a lot of people who ought to be there.” A whole industry has emerged to manage just the discovery of electronic records.

In part, the e-discovery solution may lie in emerging predictive coding technology, which uses statistical methods, categorization software and artificial intelligence to wade through millions of digital documents to find smoking-gun documents for litigation. The technology was first approved in a reported case in the 2012 matter Da Silva Moore v. Publicis Groupe. Recent research shows machines are already as effective as humans in many cases.

Of course, thanks to social media, networking is now often an entirely digital affair.

In particular, LinkedIn, which launched in 2003 and has become a prime online location for lawyers to network and for clients to research an attorney’s background.

And since 2006, Twitter has provided a place for lawyers to post 140-character messages for the world.

Are you a small-firm or solo practitioner who can’t afford expensive information technology? Thanks to cloud software, which may have been first mentioned in 1996, you can now rent applications without having to manage the IT overhead.

THE LAW SCHOOL REVOLUTION

For much of American history, lawyers like Abraham Lincoln could succeed with little formal education. In 1923, the ABA began approving law schools according to its standards. But as late as 1951, 20 percent of American lawyers had not graduated from law school. Half of those had not graduated from college.

By 1960 lawyer wannabes had to graduate from college, endure three years of law school and persuade a bar committee of their high moral character in order to practice law.

In 1945 Frank H. Bowles, admissions director at Columbia Law School, suggested law school applicants take “a law capacity test” to smooth the admissions process. Now the LSAT is the primary way into most law schools. Hate them or love them, the U.S. News & World Report college rankings, started in 1983, have had an enormous effect on law school applications and admissions, on hiring prospects after law school, and on the willingness of students to take on heavy student-loan debt in hopes of making the money track in a legal career.

Diversifying the profession is obviously a moral issue, but it is also an innovation, as increased diversity of the bar and on the bench brought new insights and perspectives to the practices of law. The ABA lifted its ban on African-American lawyers as members in 1943. And greater diversity has led to the development of trailblazers, including Louis Brandeis, Thurgood Marshall and Sandra Day O’Connor.

Shutterstock.com

INNOVATION OR INVASION OF PRIVACY?

In 1928, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis warned in Olmstead v. United States that “the progress of science in furnishing the government with means of espionage is not likely to stop with wiretapping.” And that was decades before … Internet eavesdropping became a thing. Even after the high court declared phone calls private domain in 1967, new technologies have made new types of eavesdrop-ping possible. Congress passed the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act in 1986 to balance privacy standards against the legitimate needs of law enforcement. But email, instant messaging, cloud computing, cellphones, Global Positioning Systems and geolocation tracking are just some of the technologies that have become available since those laws went into effect.

And now, GPS eavesdropping! In United States v. Jones, decided in 2012, the court ruled that use of a GPS device to monitor a vehicle’s movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment and requires a warrant.

Shutterstock.com

THE CHANGING FACE OF LAW FIRMS

Like the railroads a century earlier, the introduction of the interstate highway system in 1956 profoundly shaped tort, employment, contract, property, environmental and regulatory law. As recently as 1950, a firm of 150 attorneys was considered gigantic, and a handful existed in only the largest cities. That has changed over the last three decades with the rise of the megafirm, also known as BigLaw. Even with the ongoing contraction of the legal profession, 1,000-lawyer firms now dominate many markets across all practice areas.

In 1992, the chemical giant E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Co. decided it had to have a better way to deal with more than 300 law firms it was using for outside counsel. It introduced the DuPont legal model, using business metrics (like how many times a task is done and how many people it takes to do it) and information technology (like electronic billing) to simplify its relationships with law firms.

Martindale-Hubbell is perhaps the best-known resource for lawyers and general counsel to find other attorneys to work with. But upstart websites like Avvo (2006) have made online lawyer ratings even easier to find. Of course, lawyer ratings may be completely irrelevant now that anyone can use social media lawyer research sites like Yelp (2004) to get the scoop on an attorney.

The unbundling of legal services was allowed as legal ethics rules relaxed and lawyers were no longer required to provide all legal services to their clients. Unbundling created a whole new playing field for the profession, like We the People, established more than 25 years ago to provide legal documents to those unwilling or unable to pay for a lawyer.

And the bricks-and-mortar legal business of We the People has been put in shadow by Internet-based legal services such as LegalZoom, started in March 2001.

Outsourcing is a sore topic for any industry as domestic jobs are lost to foreign competition. Perhaps the best known of these services is Pangea3, first based in India and founded in 2004 (and now owned by Thomson Reuters). Law firms have outsourced domestic document review work, IT support and other former in-house jobs to foreign and domestic outsourcing partners. Nearsourcing has not gained the notoriety of its foreign cousin, but some BigLaw firms have found consolidating back-office services in less expensive locations—as Nixon Peabody did in Rochester, New York, in 1999—to be a viable business practice.

Shutterstock.com

NEW PRACTICE AREAS

Lawyers still defend and prosecute criminals; they help people with wills, divorces, trusts and estates; they litigate liability lawsuits. But today’s business lawyer manages IPOs, mediates billion-dollar mergers, or litigates decadeslong antitrust and copyright matters that control the fates of entire industries.

Are you self-righteous, indignant and able to extemporize on any legal topic thrown your way? You might consider a career on cable television. Highly publicized cases such as the O.J. Simpson trial and the arrival of lawyer-commentators such as Roy Black on news programs can be seen as precursors to the Nancy Graces and Greta Van Susterens of today.

Our world is the product of the satellites, space stations, telescopes and other objects that we’ve put into the Earth’s orbit over the past 50 years. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty forms the legal framework of international space law. When humans land on meteors, Mars and other space destinations, the law will certainly adapt.

Before Amazon.com can start delivering books to your door, lawyers, regulators and lawmakers have a lot of regulatory, zoning and practical details to figure out in drone law. This counts as an innovation still under development at press time.

“Drug lawyer” used to mean something dangerous or sleazy, like the Saul Goodman character from Breaking Bad. But when Portugal became the first nation to decriminalize personal drug use in 2001, resulting in dramatic drops in drug use and a big increase in the number of addicts seeking treatment, the push to remove punishment for drug use had a poster child. And as drug use is decriminalized, new business owners need lawyers who can do things like read contracts, and deal with licenses and zoning issues, as well as the mundane tasks of running a legitimate business.

Shutterstock.com

MODERN LEGAL THEORY

The Living Constitution is a concept spawned by a 1927 book of that name by political science professor Howard McBain. The basic idea is to adapt the Constitution to modern facts. Louis Brandeis, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Woodrow Wilson were some of the concept’s greatest proponents. Of course, the Living Constitution has often been eclipsed by originalism, a term coined in the 1980s, which aims to identify the original meaning or intent of the Constitution and apply it to contemporary cases. Associate Justice Antonin Scalia has become the most prominent promoter of the concept on the Supreme Court.

Economic analysis in the law aims to copy the efficiency found in economics and apply it to the law. In 1961 two groundbreaking articles, “The Problem of Social Cost” and “Some Thoughts on Risk Distribution and the Law of Torts,” marked the start of what has been called the modern school of law and economics.

In 1983, the ABA House of Delegates voted to replace the Model Code of Professional Responsibility, which had been in effect since 1969, with the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, which have since been adopted in whole or in part by 49 states.

Copyright is supposed to protect the interests of content creators, but copyright terms extend that protection to 70 years after the life of an author. Some think that is too long. Law professor Larry Lessig helped launch an alternative copyright code, Creative Commons, which makes it easier for others to borrow, remix or appropriate pieces of work while retaining some rights.

The Cooperation Proclamation, published by the Sedona Conference think tank in July 2008, is just a proposal encouraging lawyers to be more cooperative and less adversarial in the discovery process. But as judges have begun endorsing the idea in decisions, lawyers may have to find more ways to be more transparent and collaborative in litigation.

Every country has its own way of regulating libel, gambling, pornography or hate speech. But on the Internet, how do you enforce local legal standards on a global technology? Lower courts have wrestled with the issue of jurisdiction on the Internet since the mid-1990s; most of them have decided that just because a website is available to all does not provide general jurisdiction. But the Supreme Court has not taken up the issue so far.

War crimes have been prosecuted since medieval times, but the modern war crimes prosecution is a recent innovation. During World War II, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin proposed summarily executing up to 100,000 German staff officers. Even British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had urged that Nazi leaders be “hunted down and shot.” But those favoring a legal process prevailed with the creation of an international military tribunal at Nuremberg commissioned to try German officials accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The first Nuremberg trial opened in November 1945 and ended in October 1946, with 12 defendants sentenced to death and seven receiving prison sentences, while three were acquitted.

Due in part to the establishment of the International Criminal Court in 1998, war criminals have been prosecuted following conflicts in several countries and regions of the world, including the Balkans, Liberia and Rwanda.

STREAMLINING LAW PRACTICE

The creation of new federal agencies in the wake of the New Deal was an important event, but perhaps the more important innovation was the Administrative Procedure Act, passed in 1946, which helped make sense of the duties, roles and responsibilities of all of those organizations. American civil procedures are an odd and continually evolving mix of precedents, tradition and common sense. Thankfully, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, established in 1938, have been continually updated to standardize our otherwise unruly legal practices.

Legal class action got its modern rebirth in 1966, with a major revision of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The change established the opt-out option, making all members of the class a part of the lawsuit unless they object in court.

Some lawyers dread pulling out their blue Uniform Commercial Code, first published in 1952, but uniform laws make sure all states have the same rules for certain legal issues.

As the jury trial disappears, arbitration has emerged as a faster, less adversarial and cheaper dispute-resolution mechanism. The Federal Arbitration Act of 1925 established a public policy in the U.S. for arbitration. American criminal enterprises had a lucrative 20th century. Fortunately, American lawyers invented racketeering laws, including the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act of 1970. RICO allows law enforcement to charge a person or group of people with running large-scale criminal enterprises.

Oh, wait—here’s one more: Underlying the creation, spread and evaluation of so many of the innovations and inventions on this list is the great American tradition of spirited debate, now most commonly exhibited in online comments. So make use of this innovation and tell us what we forgot, what we shouldn’t have included and what you like best about the innovations of the last 100 years.

Jason Krause is a freelance writer based in Madison, Wisconsin.