'The Practice' vs. 'Boston Legal': How the original stacks up to the spinoff, part 1

Steve Harris (far left) and Michael Badalucco (center) star as partners Eugene Young and Jimmy Berluti on The Practice. Photo by Bob D’Amico/Disney General Entertainment Content via Getty Images.

In April, Screen Rant published its list of the 10 best legal drama shows of all time, ranked according to IMDb. After review, I realized two of the 10 were very closely related. Boston Legal was a spinoff of The Practice, and also according to IMDb, the byproduct is better than the initial offering.

I never watched either series. Sacrilege? Perhaps. Nevertheless, I figured this was an excellent opportunity to introduce myself to both and see which one stands above the other.

‘The Practice’

The Practice ran for eight seasons, originally airing March 4, 1997, on ABC. The series focused on a Boston-based law firm primarily handling criminal defense cases. According to creator David E. Kelley (who also created the Amazon Prime legal drama Goliath), he conceived the show as a counterpart to L.A. Law (which he wrote for and later executive produced).

Most of the storylines centered on the attorneys—Dylan McDermott as senior partner Bobby Donnell, and Steve Harris and Michael Badalucco as partners Eugene Young and Jimmy Berluti, respectfully—as they tackle their roles in the courtroom and the underlying friction those positions create for a person’s conscience. The series ended on May 16, 2004, but not before earning 15 Primetime Emmy Awards and spawning Boston Legal, which premiered on Oct. 3, 2004.

‘Honor Code’

Those familiar with my column know that whenever I set out to review a television series as a whole, I try my best to explore the top-rated installment. As such, I use Episode Ninja to zero in on the highest-ranking episode. The Practice was listed in the database, and I soon found myself headed to Hulu to view “Honor Code,” the sixth episode in the series’ sixth season.

I was hoping for something earlier in the series, but the (self-imposed) rules are the rules.

At this point in the timeline, an insurance defense firm is attempting to hire Donnell’s firm to assist with an upcoming jury trial. Donnell reminds the insurance attorney that his firm primarily handles criminal defense and doesn’t do much civil work. Still, the insurance firm believes they will have a primarily blue-collar jury (which is why they want Berluti) and they note that the plaintiff is African American (which is why they want Young). Donnell and his colleagues accept the offer and start to prepare for the upcoming trial.

(As a quick aside, I have to mention one thing: I’m not a fan of the series’ introductory theme music.)

We pick up with an impressive courtroom scene. The plaintiff, a young African American boy, testifies regarding the injuries he sustained from the car accident at issue. Young handles the cross-examination masterfully. As an attorney who defends many cases involving juvenile victims, I know how difficult that task is. Thankfully, Young does a great job of confronting the boy with kid gloves.

After the court adjourns, a medical professional approaches the defense firm to discuss issues that arose while one of the staff physicians reviewed the plaintiff’s injuries for trial preparation. The boy’s injuries are much worse than anyone expected due to a newly discovered brain aneurysm. Without immediate surgery, the issue is life-threatening.

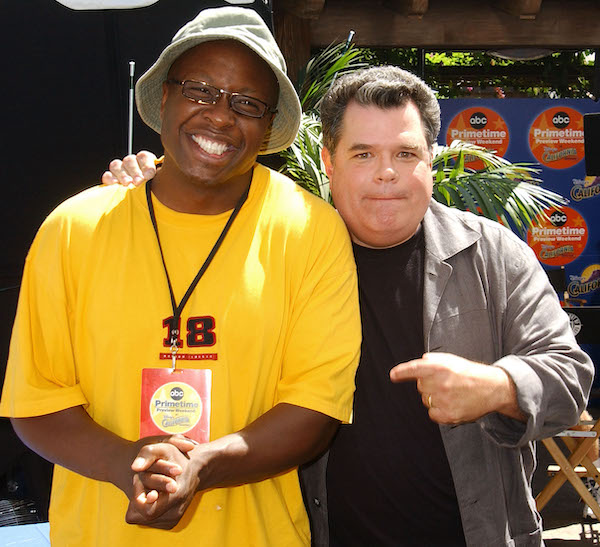

Steve Harris (left) and Michael Badalucco at the 2003 ABC Primetime Preview Weekend. Photo by Gregg DeGuire/WireImage via Getty Images.

Steve Harris (left) and Michael Badalucco at the 2003 ABC Primetime Preview Weekend. Photo by Gregg DeGuire/WireImage via Getty Images.

Client confidentiality

Donnell and his team meet with the insurance attorney to discuss the news. The insurance attorney explains they can’t relay the medical emergency to the family because they have a fiduciary duty to the insurance firm (their client). With this duty in mind, they can’t disclose information detrimental to the company’s interests.

Donnell and his attorneys push to get the information to the family that evening since the boy’s health is in immediate danger. But the insurance attorney explains they will simply accept whatever the plaintiff counters in the morning and close the case. The client has instructed them to settle the matter, and they can’t disclose the information without the client’s authorization since it is privileged work product: “The client has given us the instruction. We are ethically prohibited from revealing this information.”

I immediately thought of ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct Rule 1.6, which deals with confidentiality of information in the lawyer-client relationship. If I know a client is about to cause serious bodily harm, or if I can prevent reasonably certain death, then I’m allowed to disclose information that would otherwise be confidential.

Donnell had the same idea; consequently, he and his attorneys decide to consult with someone they have a great deal of respect for, law professor Anderson Pearson, who corrects them: “No, that is different from knowing somebody’s medical condition as a part of work product.” Apparently, the law makes that distinction in a civil matter. This was news to me; but again, I’m no civil attorney. Notwithstanding, I didn’t try to confirm or dispute the assertion, either.

Regardless, Berluti goes to the plaintiff’s home that night and informs the family—he even calls for an ambulance to meet him there. The boy goes into surgery, and everything turns out fine for him; however, Berluti has placed himself in a dangerous position regarding his bar license: He broke client confidentiality. As a result, his co-counsel (Young) reports him to the bar because, “Under the canon of legal ethics, [he] had a duty to report [Berluti] …”

The remainder of the episode focuses on the bar disciplinary hearing. Berluti delivers an impromptu closing in which he attacks the entire adversarial process for promoting lies and falsehoods between counsel. According to Berluti, it’s no longer about the truth. “And you wonder why nobody respects us …” He makes a valid point: does the bar expect the public to trust and respect attorneys when they can’t inform a family about the ticking time bomb inside their 10-year-old’s head?

What follows is a tremendous discussion about “the system” and its legitimacy. As the disciplinary board explains, though, legal ethics and morality are two very different things: “What a client tells his lawyer is sacrosanct …” Attorney don’t get to decide when they will honor the privilege and when they won’t.

A series ahead of (or behind) its time?

This episode was exceptionally well done. It won’t be the last installment of The Practice I view. However, the episode had its fair share of faults. For one, I was somewhat disappointed that the top-rated episode in a series revolving around criminal defense attorneys focused on a personal injury case. It still delivered a quality courtroom scene, but that was odd to me. Second, the bar disciplinary hearing scenes came off as a bit “preachy.” There was a distinct “holier than though” vibe. The message was good, and the questions presented were thought-provoking, but the delivery was a little too over the top for my liking.

Nevertheless, I’m glad to know there is a relatively recent long-running series out there devoted to those defending the criminally accused. Sure, How to Get Away with Murder and Better Call Saul are contemporary options that touch on criminal defense, but from my research and experience, The Practice portrays more of the litigation aspect that is so common to this specific area of the law. In that sense, The Practice felt closer to some of the classic defense attorney TV shows, such as The Defenders, Perry Mason, Matlock and the like.

Be that as it may, the other above-mentioned present-day options seem to focus mostly on the interplay between the individual characters and the collateral issues that evolve in their personal lives. Often, the practice (no pun intended) of law is an afterthought. Perhaps that’s what today’s viewing audience prefers.

Ultimately, though, I thoroughly enjoyed my initial exposure to The Practice, and I look forward to delving into the series as a whole. Up next, I’ll see how its spinoff, Boston Legal, stacks up.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.