Retired D.C. Circuit judge talks about his memoir on navigating a legal career through blindness

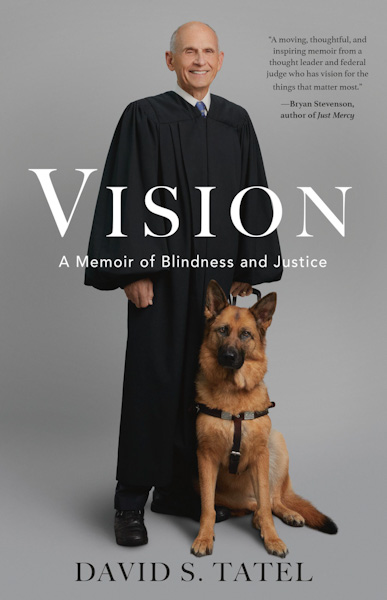

It took convincing to get Vision: A Memoir of Blindness and Justice off the ground. “I didn’t want to write a book about being a judge,” Judge David Tatel says. “I didn’t think anybody would read a book about an appeals court judge who didn’t make it to the Supreme Court.” (Photo by Deborah Feingold)

In 2007, Judge David Tatel recused himself from a case addressing whether the government was required to make paper currency identifiable to the blind and visually impaired by changing the color, shape, size and feel of banknotes.

Explaining his decision, Tatel says “I could see a conservative writer or journalist saying ‘Wait, the D.C. Circuit forced the Treasury Department to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to make currency accessible—and the blind judge wrote the opinion.’ ”

Such criticism would have been unfair, Tatel tells me in a recent interview. But he acknowledges that it may not have been unreasonable. So he stepped away from the case “to protect the integrity of my court.”

Tatel retired late last year after nearly 30 years on the federal appeals court. In all that time, he never saw a single piece of paper nor an attorney argue before him.

The former jurist—nominated by President Bill Clinton to fill the seat vacated by Ruth Bader Ginsburg following her confirmation to the U.S. Supreme Court—shares this remarkable challenge in Vision: A Memoir of Blindness and Justice.

But the various mechanics of it—such as having a law clerk put a treat on his chair, to tell the judge’s guide dog where he’d be sitting for oral argument—is just one part of the story.

In Tatel’s captivating autobiography, published Tuesday, he also addresses many personal aspects of his blindness, including whether it affected his judging. Unlike the currency case, there are a couple of others that he now regrets not passing on.

The 82-year-old Tatel introduces his guide dog, Vixen, at the beginning of his book, and apologizes to any readers disappointed that they picked up his memoir and not hers.

A role model for the blind

It took convincing to get Vision off the ground. “I didn’t want to write a book about being a judge,” he says. “I didn’t think anybody would read a book about an appeals court judge who didn’t make it to the Supreme Court.”

But friends pushed him hard, he explains, to tell his unique story. What clinched it for him was that it could be inspirational.

Tatel, afflicted with retinitis pigmentosa, began to lose his sight as a teenager. In denial of his deteriorating vision, he employed a host of tricks to cover it up. In law school, he found a table in the library with the brightest lighting and took notes with a thick black pen. Blackboards were a challenge so he borrowed classmates’ notes but without revealing why. But not until he was nearly 40 and began using a white cane, Tatel says, did his “subterfuge” end.

Tatel says that he “didn’t have any role models of blind people.” Perhaps his book could fill that gap. And “maybe partners in law firms will read this book and say ‘you know, we should have hired that blind guy we interviewed the other day. Obviously, he can do the work.’”

Tatel wrote Vision with his wife, Edie, a PhD who taught writing at the college level. The collaboration made for interesting discoveries. He found out that, at the time of their first date, “she was dating two other guys, ‘Ralph’ and ‘Teddy.’”

Tatel grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland. With his father a physicist, who even had a telescope named for him, science and math dominated the household. Tatel attended the University of Michigan to prepare for a career in that field.

But then, Tatel says, he was “captured by the 1960s” and switched his major to political science. He was inspired by what was happening in Ann Arbor, an epicenter of student activism. He decided to take summer internships at the Labor Department in the nation’s capital. Seeing the role that lawyers were playing in the civil rights movement, Tatel headed to the University of Chicago Law School.

Tatel took various public service positions after graduation, serving as founding director of the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and then as director of its National Committee. During the Carter administration he held the top job in the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. He also had a long career at Hogan Lovells, in Washington, D.C., founding and leading the firm’s education practice.

Judge David Tatel, 82, and his guide dog, Vixen, who he calls, “the dog who changed my life.” (Photo by Edie Tatel)

Judge David Tatel, 82, and his guide dog, Vixen, who he calls, “the dog who changed my life.” (Photo by Edie Tatel)

On the bench

Throughout his time on the bench, advancements in technology for the blind dramatically altered how Tatel adjusted for his lack of sight.

The volume of documents in many of his cases was massive. He relied on his law clerks to pick out the parts of the record that he needed to know. At the start, he recalls, just about everything had to be read to him by individuals hired by the court.

But over the last few years, thanks to the development of various text-to-voice technologies, Tatel says he needed a human reader for only 5% of the material that crossed his desk.

These days, Tatel, back at Hogan Lovells where he plans to mentor young lawyers and provide assistance to its pro bono program, does not use a reader.

Tatel writes that he always did his best to ensure that his blindness did not affect his judging but adds, “There’s no way I can be 100% sure … there’s no case I would have seen differently if I could have, well, seen.”

In 1995, Tatel was on the panel that heard Boggs v. Bowron. J.S.G. Boggs, a renowned artist with a talent for drawing realistic currency, but with some playful aspects, explained to merchants that his banknotes were art and exchanged them for goods and services in the amount of their face value. The Secret Service had a different word for it and sought to put an end to the bartering. Boggs claimed First Amendment protection.

Tatel’s daughter spent hours describing each bill to him and he felt comfortable hearing the case. The artist lost—in a unanimous decision.

In another one, involving the alleged copying of an architectural design, Tatel had a clerk explain the designs’ similarities and differences to him. The court denied summary judgment and sent it back for a jury to decide.

Tatel now says that he should have recused himself from both cases: “I’m the judge. I’m the one that has to make the decision. If the description I was getting in those two cases, from the person explaining it to me, reflected their views of the issue, then that would be inappropriate.”

On the other hand, he also wonders whether his blindness helped him to be more objective. Of his inability to see the lawyers arguing before him, Tatel writes that maybe he was “a tiny bit lucky to resemble Lady Justice in at least [one] respect: I wasn’t influenced, even subconsciously, by how the advocates appeared.”

At his writer-wife’s insistence, in over 700 opinions, he never used a single footnote. Such writing technique, Tatel explains, is “your excuse not to think about aspects of the opinion.”

While Tatel says he loved his job, and could still do it, his decision to retire was made to ensure the current president chose his successor. His view of the current Supreme Court, which he says has shown a “disrespect for stare decisis,” also played a part. His unvarnished description gets no shortage of pages in his memoir.

“It was one thing to follow rulings I believed were wrong when they resulted from a judicial process I respected,” Tatel writes. “It was quite another to be bound by the decisions of an institution I barely recognized.”

Good dog

Tatel waited a long time to get a guide dog. He says he got along fine for 40 years using a white cane. “Why would I want a dog?”

But this changed after his 11-year-old grandson shared a podcast on the subject. The seed was planted. In 2019, Tatel met Vixen, who he calls, “the dog who changed my life.”

“Vixen allows me to do many things myself that I couldn’t before, so I feel much more independent,” he says. He tells me that earlier that morning, he and Vixen went for a three mile walk, and he didn’t even tell his wife he was going.

Many dogs that set out to be guide dogs do not make the cut. Tatel says that squirrels are a problem. No matter how much training they get, for some, it is just too tempting to chase them.

“If Vixen is not in her harness,” Tatel says, “she will go after a squirrel. If she’s in her harness, she just watches them.”

Tatel good-naturedly mentions that Brando, the D.C. Circuit courthouse’s bomb-sniffing dog, is a guide dog school dropout. “Perhaps Brando had a thing for squirrels.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.