So you were convicted of killing someone who's still alive—now what?

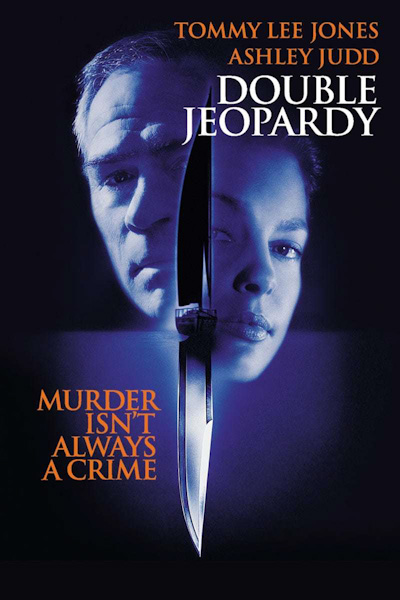

Released in 1999, Double Jeopardy stars actress Ashley Judd and actor Tommy Lee Jones. Image from MovieStillsDB.

Many installments of this column have focused on true-crime documentaries examining murder convictions and the legal process and “evidence” that led to them. While those series or stand-alone shows are undoubtedly intriguing, we always seem to be left with the same conclusion: Even if the defendant didn’t kill the person, the person is still dead. But what if we were presented with a situation in which someone was convicted for the murder of a person who was subsequently found alive and well?

I’ve done a cursory search and haven’t turned up documentaries related to what would essentially be an infrequent occasion in my experience. Still, though, the idea is a provocative thought project. Obviously, no one wants anyone to suffer that fate to create some sort of true-crime entertainment for the rest of us. But luckily, we have some fictionalized stories that illustrate a fascinating aspect of the criminal justice system that, while rare, isn’t impossible.

Double Jeopardy (the movie)

Released in 1999, Double Jeopardy stars actress Ashley Judd as a woman scorned. While the audience’s initial introduction to the protagonist presents what appears to be a charmed life, Judd’s character, Libby, is eventually tried and convicted of killing her socialite husband, allegedly stabbing him to death and throwing his body overboard from a beautiful sailboat that the two were taking out for a weekend test before buying.

Before I delve further into the storyline, please, for the love of all that is holy, take this one piece of advice from me: If you ever stumble upon a bloody knife, don’t pick it up. No matter how distraught or how much you want to investigate, just don’t do it. Please.

Libby quickly finds herself in a women’s prison, where she grows close to a few female inmates who have also been convicted of murder. They bond over a common hope: That their love for the children they’ve left behind will be reciprocated if and when they are finally released.

Libby eventually loses contact with her young son and inadvertently discovers that her presumed-dead husband is still alive and well, living a new life with her child. As luck would have it, one of the fellow inmates coincidentally was a practicing attorney before losing her license as a result of her murder conviction. However, instead of offering advice on finding her son or assisting with a jailhouse appeal, the ex-attorney explains to Libby that her best bet is to simply sit tight until she is released.

She’s already been convicted of killing her husband. Once she gets out on parole, she can take his life without consequences. And so the stage is set for her righteous retribution. I won’t ruin the ending, but know that the movie is good for what it is: A story of a mother’s revenge.

Double jeopardy (the legal theory)

The principles of double jeopardy stem originally from the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. There, we find the framers’ directive that “No person shall … be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.” The idea is fairly straightforward; you can’t be prosecuted more than once for the same offense after “jeopardy” attaches.

More often than not, we see this protection arise in situations such as a jury trial. When we discuss the notion of “jeopardy attaching,” that happens in a jury trial once the jury is empaneled and sworn in.

A similar but somewhat-procedurally different scenario happened in one of my recent jury trials, where my client was charged with first-degree murder. At trial, the prosecution initially relied on a theory of premeditated murder. That changed; the evidence elicited through testimony, and the admitted exhibits cast doubt on their confidence in a conviction.

When this happens, prosecutors often ask for a lesser-included offense. We have previously talked about different degrees of homicide, so I won’t go into great detail regarding that aspect. Regardless, in this trial specifically, the prosecution requested a lesser-included alternative charge of first-degree manslaughter. They knew that they had a better chance of securing a conviction with that, rather than first-degree murder.

After about nine hours of deliberation, my client was acquitted of the first-degree murder charge; he was convicted of first-degree manslaughter, though. Afterward, some potential issues regarding jury deliberation were brought to my attention. My client and I discussed the possibility of pursuing a new jury trial based on the errors that potentially arose while the jury decided his fate.

As we discussed his options, my client was understandably concerned about being tried again for first-degree murder. After all, a jury trial can a crapshoot depending on the 12 people fate pushes your way. That danger is exacerbated by the fact that the only sentences available in Oklahoma after a conviction for murder in the first degree are life in prison with the possibility of parole or life in prison without parole. There’s no middle ground.

I showed him the verdict form where the jury marked “not guilty” regarding the first-degree murder charge. I further explained the relevant U.S. Supreme Court caselaw holding that when someone is acquitted of a charge at jury trial, that acquittal can never be taken away, even if a new trial is ordered for whatever reason. In fact, the high court’s precedent states that even if a jury did not specifically mark “not guilty” on the verdict form for the first-degree murder charge, a conviction for a lesser-included offense is an implied acquittal of the greater allegation.

‘No Body, No Crime’ and corpus delicti

Consequently, double jeopardy does play out in the criminal justice system more often than people may realize. However, situations such as the exaggerated instance portrayed in Double Jeopardy the movie seem to be few and far between.

Still, the film got me thinking: Are there any actual instances of someone being convicted for the murder of a person who was not dead? Sure enough, CNN was ready and willing to help out with a story published in 2009. Most of the instances discussed are centuries old, but there are a few that have happened relatively more recently. It’s an interesting read.

One final point: Some readers who don’t practice criminal law may have heard the phrase “corpus delicti.” To be clear, the term doesn’t really refer to the corpse in a murder case. It’s a Latin phrase that translates to “body of the crime.” I could see how that short and sweet translation might make someone think that the prosecution needs an actual dead body to move forward with a murder prosecution, but that just isn’t the case.

In practice, corpus delicti simply stands for the position that a crime must be proven to have happened before a person can be convicted of committing that crime. Prosecutors usually attempt to accomplish this by relying on circumstantial evidence. After all, if the circumstances of a situation show beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime was committed and that the accused was the perpetrator, then a conviction will likely follow.

So sorry to all you Taylor Swift fans out there. “No Body, No Crime” isn’t the law of the land.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.