Law professors Stephen and Barbara Gillers turn breakfast chats into legal ethics podcast

Image from Shutterstock.

It all started with John Dean, Stephen Gillers tells me. In 1973, Dean, President Richard Nixon’s White House counsel, testified at the Senate Watergate hearings. He provided the committee investigating the scandal with a list of those likely to be indicted for their roles. Dean put asterisks next to those who were lawyers. There were 10.

“That was an electrifying moment for the legal profession,” Gillers says. The renowned legal ethics professor explains that it prompted the profession to ask why “so many lawyers violated ethical rules or even criminal law and went to prison. Were law schools failing? Was the ABA failing in not ensuring adequate legal ethics instruction?”

The following year, the American Bar Association adopted a law school accreditation requirement that students receive instruction in legal ethics.

Gillers has been filling that role for New York University School of Law since 1978. But his influence in the area of professional responsibility has extended far beyond the Greenwich Village campus. Gillers’ case book on the subject, Regulation of Lawyers: Problems of Law and Ethics, has been used at dozens of law schools since 1985.

The 77-year-old Gillers sometimes has company during his commute from the Upper East Side. His wife of 41 years, Barbara Gillers, has been an adjunct professor at the law school since 2009. She, too, focuses on legal ethics. Her accomplishments include having chaired the ABA Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility and the New York City Bar Association’s Committee on Professional and Judicial Ethics.

I wonder how the two avoid talking shop at home. They don’t, they tell me. And it’s welcomed. “We love it. It’s a great part of our lives,” Barbara, 73, says.

“If Barbara were an antitrust lawyer, I’d have to talk to myself,” Stephen quips.

Stephen points to interesting breakfast conversations they have over legal ethics aspects of stories in the news. One day he posited to his wife, “Wouldn’t it be nice to record our breakfast conversations?”

Photo of Barbara Gillers by ©Hollenshead: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau.

Photo of Barbara Gillers by ©Hollenshead: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau.

Ripped from the headlines

And that’s what they’ve been doing since May, when the New York City Bar Association launched their podcast, Legal Ethics in the News, a look at professional responsibility in the context of headline stories about lawyers and judges in the legal and mainstream media.

During a phone interview from Nantucket, Massachusetts, where they were vacationing, the duo discussed their program. Episode topics have included Rudy Giuliani’s interim suspension from the practice of law in New York, litigation financing, prosecutorial misconduct and attorney-client privilege issues concerning the upcoming fraud trial of Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of blood-testing company Theranos, Inc. The program also has covered more general issues, such as a not-to-be-missed “10 Reasons Lawyers Mess Up” list, a compilation of lessons the legal ethics experts identified over decades of having seen it all.

Given their experience, the risk of venturing into inside baseball seems high. But the podcast hosts deftly avoid getting bogged down in minutiae.

The law professors tell me they have long been borrowing from the news as part of their class instruction. “We try to raise the more interesting examples that show that this is not abstract. This is happening to people every day,” Stephen says. They were “blessed” with the Trump administration, because the lawyers “just threw off so many juicy issues … . The two Michaels—Avenatti and Cohen—alone gave us two weeks’ worth of anecdotes.”

The couple’s program has tackled a subject of great interest lately to many lawyers: remote practice. Barbara tells me ethical issues surrounding lawyers working for a firm but from a jurisdiction where they are not admitted to practice are not new. The pandemic, however, she adds, has “let the genie out of the bottle.”

She explains that the issue comes under Rule 5.5 of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, addressing the unauthorized practice of law. Lawyers practicing this way, Barbara says, have only a “technical risk” of violating the rule because the conduct is unlikely to interest disciplinary bodies and because the Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility’s Formal Opinion 495, adopted in December 2020, “gives some comfort.” It states that in the absence of a prohibition in the local jurisdiction’s unauthorized practice law in, for example, a statute, rule, case law or opinion, a lawyer who is “for all intents and purposes invisible as a lawyer to a local jurisdiction where the lawyer is physically located but not licensed” is not in violation of the ABA model rule. By “invisible,” the opinion refers to such things as the lawyer not advertising or otherwise holding out their presence or availability to perform legal services in the local jurisdiction.

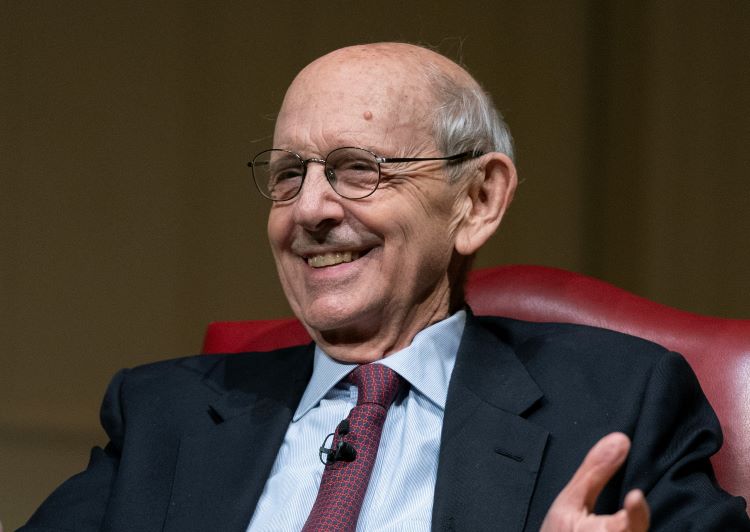

Stephen Gillers. Photo courtesy of the New York University School of Law.

Stephen Gillers. Photo courtesy of the New York University School of Law.

Weighing in on Florida CLE ruling

In April, the Supreme Court of Florida, on its own motion, amended Rule 6-10.3(d) of the Rules Regulating the Florida Bar, which governs course approval for continuing legal education. The Florida high court struck down a policy adopted by the Business Law Section of the Florida Bar that imposes a minimum number of diverse faculty for courses—based upon race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability and multiculturalism.

Although the court stated it understood “the objectives underlying the policy at issue … quotas based on characteristics likes the ones in this policy are antithetical to basic American principles of nondiscrimination.”

Stephen speculates that “since a diversity requirement does not reduce quality [of CLE] and will often increase it, the decision can only be justified by the court’s hostility to quotas generally.” He fears “that there’ll be copycat state high courts and it will turn out to be red [state] versus blue [state].”

Barbara adds that by the court’s application of the rule to all CLE providers, not just those sponsored by the Florida Bar—over which the court has jurisdiction—“an unfortunate effect of this rule may be to pressure organizations over which the court has no jurisdiction to change their rules so that their CLEs remain attractive to Florida lawyers.”

The ABA filed lengthy comments with Florida’s top court, asking that it “clarify its opinion by distinguishing between forbidden quotas and a policy, such as the ABA’s, that promotes only inclusion and does not run afoul of equal protection guarantees.”

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s recent rule change

Another state high court recently issued an opinion addressing the regulation of lawyers. In July, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court amended Rule 8.4 of the commonwealth’s Rules of Professional Conduct, declaring it professional misconduct for a lawyer, in the practice of law, to “knowingly engage in conduct constituting harassment or discrimination based upon race, sex, gender identity or expression, religion, national origin, ethnicity, disability, age, sexual orientation, marital status or socioeconomic status.”

The decision was a response to a 2020 decision from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in Greenberg v. Haggerty, where the court struck down an earlier version of the rule that proscribed a lawyer from knowingly manifesting “bias or prejudice” in the practice of law. The rule was successfully challenged by a lawyer who argued that he could run afoul of it on account of using epithets, slurs and demeaning nicknames during CLE presentations.

Stephen predicts that the new Pennsylvania rule will be tested in court. “The intensity and ferocity with which the opposition has challenged the constitutionality of a rule that essentially forbids sexist and racist comments, in representation of a client, directed at an opposing party or lawyer, is impossible for us to understand,” he says.

The professors’ “10 Reasons Lawyers Mess Up” list contains mistakes such as working under a bad mentor and acting improperly due to a demanding client or psychological pressure.

Their tally also includes what they term “rationalization,” which Stephen explains involves a lawyer who, through a torturous or strained interpretation of the law or rules, convinces herself “that her conduct or goal is at least arguably allowed.” While lawyers are trained to find helpful meaning in texts, he adds that “there’s a point beyond which the English language cannot credibly be stretched. The aggressive interpretation of a document is simply not defensible.”

Barbara says she addresses this risk with her students by “remind[ing] them how smart they are and how they can come up with really good, clever interpretations and arguments. [But] they have to sit back and think twice, and talk to perhaps a seasoned lawyer, perhaps a colleague, perhaps ethics counsel, before actually putting it into a brief or making the argument to a court.”

I suggest to the couple that a career spent focusing on legal ethics seems depressing. Stephen sees my point. “I think there’s an aspect of is that encourages pessimism,” he says. “You don’t hear about happy clients and happy lawyers. You hear about problems … . People don’t call you up and say, ‘I had a great experience with my lawyer.’”

But Barbara is quick to note that the glass can also be half-full: “Lawyers take these rules very seriously and they want to do the right thing, and I find that very hopeful and positive.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.