Netflix's 'Operation Varsity Blues' and the morality of parenthood

Photo courtesy of Netflix.

My son is weeks away from turning 3. Age 2 has been somewhat challenging, so I’m starting to believe all the horror stories friends have told my wife and me about “threenagers” and the difficulty they present.

His personality is flourishing, and it grows more every day. But as his personality develops, so do the intricacies of every part and parcel: His strong will can become bullheadedness, and his quick wit? A smart mouth with minimal filter or hesitation. But I see so much of myself in him that I can’t help to be flattered beyond measure.

And I know that tougher times are ahead. I should, and do, enjoy these days for what they are. I know one day he won’t be my baby boy anymore, so regardless of the tantrums and the unexplainable outbursts, I soak up as much as I can because I love him unquantifiably.

Here’s what I think a parent’s role in life ultimately adds up to: Love your child, and most of the rest will figure itself out. Still, everyone knows we must temper the love we feel and exude in accordance with time, place and circumstance. Secondary to loving our children, we have to teach them and present correct conduct in which they can model their behavior.

‘The College Admissions Scandal’

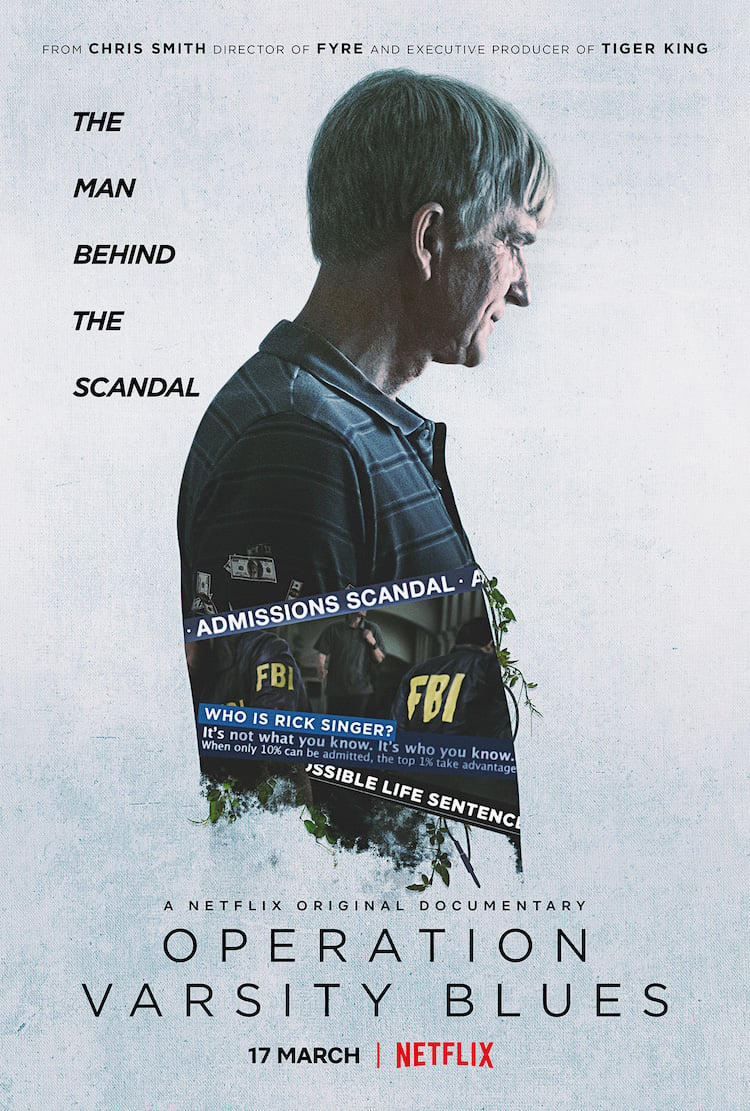

That is what makes Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal so interesting from the perspective of a criminal defense attorney. The Netflix one-off program is 100 minutes of background and insight into the 2019 scandal that drew quite a bit of national media attention.

Unlike many of Netflix’s “true crime” offerings, Operation Varsity Blues adds something that the streaming network doesn’t employ nearly as much as it should: re-creations. I thoroughly enjoyed the dialogue knowing it comes from actual wiretap transcripts.

The production, initially released in March 2021, stars Matthew Modine as Rick Singer, the mastermind behind the admissions scandal. The man received millions of dollars over decades of “side door” deals assisting parents with their children’s admission into universities they otherwise couldn’t have gotten into.

The show also interposes interviews with actual individuals involved in the scandal. The audience hears from plenty of people—prosecutors, FBI agents, former Singer clients, educational consultants and college counselors— with knowledge of the events.

If you’re like me, your ears may have perked up in confusion upon hearing the term “side door deal.” The show goes on to explain the term, more or less, as follows: When someone gets accepted into a university through the standard admissions process, they get in through the front door; when they’re admitted due to a large donation to the university, admission is through the back door; and when they get in through Singer’s methods, they’re admitted through the side door.

In a nutshell, this side door deal amounted to contributing to Singer’s organization so he could then bribe a coach or athletic director to get your kid into a school. A side door donation to Singer was much smaller than your traditional backdoor donation directly to the university, so the bribe was an affordable alternative. But it wasn’t always “just” a bribe.

Since Singer usually worked with members of the universities’ athletic divisions, he had to create fictitious athletic backgrounds for many of the students. From water polo to rowing teams, he would “coach” the parents on how to provide him with the documentation he would need to bolster their children’s fabricated athletic profiles.

Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Photo courtesy of Netflix.

What about the Heinz dilemma?

It’s fair to assume a fair number of parents conspired in the scandal merely to justify their selfish needs. Their child’s education was more of a personal status symbol than a necessary tool. To be fair, I do believe some individuals paid Singer because they genuinely wanted the best for their offspring. And truth be told, other adults find it hard to fault these parents for using their funds to “guarantee” their children’s higher education.

After all, who among us wouldn’t do everything and anything they could for their children? Sure, there are degrees and there are limits, but if there’s one aspect of life where adults collectively lose their objectivity, it’s probably the well-being of their children.

Back in my undergrad days as a philosophy major, one of the thought experiments we engaged in was the Heinz dilemma. The basic structure goes something like this: Your loved one is sick and only one man has the medication to help, but that man either will not sell the medication or is drastically marking up the price to the point where few people can afford it. So if you weren’t in a position to pay for it, would you steal the medication to save your loved one?

Do you steal the medicine?

If we apply that line of thinking to the college admissions scandal, you see some correlations. Your child needs an education, and the school either won’t allow them admission or the cost to make a backdoor donation is too high. Do you commit a “bad” act to get them into the university?

The obvious distinction here is that college admissions aren’t life-threatening illnesses, and the children of Singer’s clients could almost certainly get into some school somewhere. But here’s the underlying question: Is it always wrong to steal, no matter the circumstances, or are there exceptions to the rule? And as it applies to this article, is it always wrong to lie?

Ethics vs. morality vs. criminality

Some might argue that the terms “ethics” and “morality” are interchangeable and used to describe the same thing. However, that’s dumbing down the discussion far too much. I, along with others, distinguish the terms from the objective and the subjective perspectives.

Ethics is an objective standard used to describe what should be considered good and bad within a particular group of individuals or a specific aspect of society. Morality, on the other hand, is more in line with an individual person’s subjective belief as to right and wrong from a personal perspective. It’s a subtle distinction, but it’s one worth noting, especially when you add in the element of criminality.

Criminality is behavior that is forbidden by criminal law. Although criminality is often a derivative of ethics (since legislators create laws—in theory, based on the sentiments of their constituents), it is still separate and distinct. Something can easily be a criminal violation even though it wouldn’t necessarily be an affront to another group’s ethics or an individual’s morality.

So in light of those distinctions, where can we place the actions of the parents involved in the college admissions scandal? As the Heinz dilemma so beautifully illustrates, their actions were definitely criminal, but criminality is not necessarily objectively (nor subjectively) wrong, per se.

After all, two defendants in the scandal (Lori Loughlin and her husband, Mossimo Giannulli) received federal prison sentences for their actions, and many others were sentenced to prison as well. Was prison the appropriate sanction, though?

I don’t know if there is a right or wrong answer.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.