Not in Kansas anymore: A former congressman’s improbable journey from the heartland to Hollywood

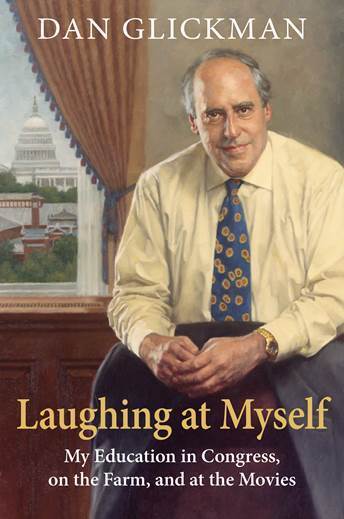

Dan Glickman. Photo courtesy of Dan Glickman.

In 2004, Dan Glickman began a six-year stint as chairman and CEO of the Motion Picture Association of America. That may seem like an unusual career change for a nine-term congressman from Kansas and former secretary of agriculture. People sometimes questioned his qualifications to lead Hollywood’s trade association. “I used to grow popcorn,” he tells me he’d respond. “And now I sell it.”

Glickman’s array of leadership positions share a trait: the need to find common ground among competing interests. In his just-published memoir, Laughing at Myself: My Education in Congress, on the Farm, and at the Movies, Glickman, also a former trial attorney, recounts how he did just that.

In a phone interview from his home-turned-pandemic office in Washington, D.C., Glickman says that “self-deprecating humor is one of the keys … to exert good leadership and minimize conflict and getting people working together.” It also convinced people, he says, to like and trust him, “and in the process get things done.”

The 76-year-old former Democratic lawmaker lays part of the blame for “the toxicity of American politics” on having become “a humorless society.” He adds: “Everybody is just so uptight, and nobody just takes a deep breath and relaxes.” Through his book, a five-year writing effort, Glickman is hopeful that “the rest of society at various levels, but particularly the high-government level, might find [his approach] useful.”

Glickman’s road to nearly a quarter-century in politics began in the proverbial mailroom. While a student at George Washington University Law School, he worked for Sen. Peter Dominick, a Colorado Republican. Glickman earned $5 an hour to open the senator’s letters and operate the autopen, a device that automatically signed Dominick’s name to correspondence that left the office.

Glickman moved up the ranks to more meaty work. Along the way, he came to understand “what impact I could make via the legislative process.” He was “hooked.”

Following graduation in 1969 and a brief stint as an attorney for the Securities and Exchange Commission, Glickman and his family moved back to his native Wichita, where he went into private practice.

The nascent lawyer’s first case foreshadowed the career in agriculture that was to come—he represented a firm client in a dispute over the ownership of 33 Russian olive trees. Glickman won, but he laughs about having spent about 4,000 hours to secure a $10,000 verdict. “But it was my great first victory practicing law,” he says with pride—“the Russian olive tree case.”

Glickman goes back to Washington

After a few years back home, including, importantly, having made a name for himself as a member of the Wichita School Board, Glickman was ready to run for public office. He challenged Garner Shriver, a Republican who had represented Kansas’s 4th Congressional District for 16 years.

Glickman focused his campaign on the district’s farmers and rural voters, arguing that Shriver had ignored them while in Congress. The strategy worked, and in 1977, he took a seat in Congress.

Glickman says disagreement with his own party on some issues reinforced for his constituents that he was “his own man, not some party hack.”

For example, in an effort to punish the Soviet Union for its 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter imposed an embargo that prevented U.S. grain from being exported to the Soviet state. Glickman opposed the Democratic president, calling the embargo “near catastrophic” for Kansas farmers already struggling to hold on to their farms.

The embargo, Glickman says, was an “early catalyst” in turning many farmers and others in grain-producing areas into lifelong Republicans.

In an unusual move for a Democrat, Glickman took on trial lawyers. With a district that included such companies as Cessna, Beech and Learjet, Glickman supported passage of the General Aviation Revitalization Act, a bill limiting the time that an aircraft manufacturer could be sued except in the case of gross negligence or willful misconduct. The law would be a boon for these constituent companies.

GARA was signed into law in 1994. With nearly 20,000 people employed in the aviation industry in Wichita, Glickman thought this legislative success would assure his reelection. He would be proved wrong.

By this time, things had changed in politics. Social issues began to take center stage in elections, and Glickman says it was “becoming more and more difficult to survive as a Democrat in the state of Kansas.” He adds, “I was genuinely liked by many of my constituents, but they would not vote for me, no matter how well I delivered for them on a slew of other matters because I was not 100% in line with them on guns or abortion or both.” Glickman was pro-choice and supported the 1994 Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act, which included a ban on semiautomatic weapons.

Less than three months after GARA was passed, he was unseated by Republican Todd Tiahrt, a one-term state senator.

But Glickman wasn’t jobless for long. Months later he was sworn in as President Bill Clinton’s secretary of agriculture. “How else but with a sense of humor,” Glickman says, “or at least a sense of irony, can you be a Jewish secretary of agriculture advocating for the pork industry?”

While serving as the nation’s farmer in chief, Glickman says, he had “probably my biggest achievement in public life.” Ironically, while his time as a lawyer had been brief, the accomplishment involved a massive federal class action filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Not to mention, it bore his name.

Pigford v. Glickman involved claims by African American farmers who alleged racial discrimination in the improper denial of farm loans as well as other racially motivated mistreatment at the hands of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Glickman oversaw a partial settlement of the litigation in excess of $1 billion.

The former agriculture secretary is hard on himself for not having known about the plight of African American farmers, despite having spent 18 years on the House Agriculture Committee. “This just shows what a major problem this issue truly was,” Glickman says, “that it had not been the focus of the legislature or the department.”

Hollywood is calling

Following nearly six years running the USDA, Glickman took a position at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. But just two years later, he got a casting call and became the leading man at the Motion Picture Association of America. The MPAA, now called the Motion Picture Association, is the advocacy arm for several of the nation’s largest film studios. The organization also assigns film ratings.

The man who now walked the red carpet at the Academy Awards was not in Kansas anymore.

Glickman used people’s shared love for movies to try to “break down the walls between conservative politicians and liberal Hollywood,” he says. “What I found is that bringing people over to the MPAA for screenings, dinners—as long as it was bipartisan—you could really build allies.”

While people in Hollywood generally get along, Glickman says collaboration is a more important requirement in Washington. “Politics just demands [it],” he says. “In politics, your enemy today has got to become your friend tomorrow because you can’t have permanent enemies in politics. If you do, you’ll be a big failure because you need allies. And our allies change based on the issues.”

These days, Glickman is a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and vice president of the Aspen Institute, organizations that are both focused on promoting solutions to the nation’s problems.

In January 1977, Glickman served as the “designated survivor” during the State of the Union address. He would become commander in chief if every person before the secretary of agriculture in the presidential line of succession was wiped out during the speech. The White House had called Glickman’s chief of staff to see if he was available. It “wasn’t exactly a call to vet my presidential qualifications,” Glickman quips.

He needed to get out of Washington. He chose to hole up in his daughter’s apartment in Lower Manhattan. He landed at LaGuardia Airport and a three-car motorcade, including presidential-level Secret Service agents, a physician and a military officer—with a briefcase attached to his wrist, presumably carrying the nuclear football—took him to his destination.

“Sir, the mission is terminated,” one of the agents announced after the speech ended without incident. The entourage left, but Glickman stayed in New York to have dinner with his daughter. They left the restaurant and went out into an unrelenting rain. Unable to get a cab, the two walked 10 blocks, arriving home drenched and freezing.

“S- - -,” Glickman says, “a few minutes earlier I was almost the leader of the free world, and now I can’t even get a cab.”

But this is more than just an amusing anecdote for Dan Glickman; it’s a valuable life lesson: “Whether it’s business or academia, but particularly in politics, you can be king of the world today, but you can be down in the depths of hell tomorrow,” he says. “The question is, can you get up?”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.