Examining juvenile crime and punishment in songs

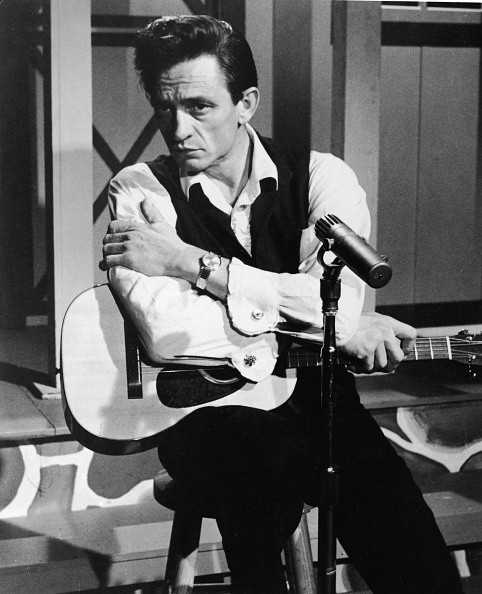

American country singer Johnny Cash sings in a still from the 1969 film Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music, directed by Robert Elfstrom. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

With fantasy football season over (home league champion, right here), I’ve started going through the back catalog of some of my favorite podcasts, one being Ryan Holiday’s The Daily Dad. I’ve previously written about his The Daily Stoic podcast, and they are both worth a listen.

I recently came across an installment titled “Tell Them Before It’s Too Late.” According to Holiday’s show notes, “An accident, a mistake—no matter the intention, no matter how sweet the child or loving the parent—can irrevocably change a life.” Throughout the short discussion, Holiday expounds on high-stakes everyday life choices and the fact that those choices can often have life-altering results, which can rarely be reversed. He analyzes this idea through the prism of the song “I Hung My Head.”

I hadn’t heard that tune in decades. I’ve previously written about how music can convey legal topics, so I thought there might be something there for a future column. With this goal in mind, I decided to revisit and analyze the song myself.

‘I Hung My Head’

Singer/songwriter Sting initially wrote and recorded “I Hung My Head” for his 1996 album Mercury Falling. It tells the tale of a young man, or perhaps a boy (as Holiday describes him), who sneaks away with his brother’s rifle to practice his aim. The boy draws a bead on a man riding a horse in the distance; to his shock, the rifle accidentally fires, killing the rider.

The boy runs from the scene, throwing the rifle in a stream. Authorities eventually find and arrest him. He appears in court, and the judge ultimately sentences him to death. The song’s story revolves around themes of regret, fear, confusion and forgiveness/redemption.

Now, as I mentioned earlier, I am using the term “boy” loosely. There isn’t any discussion I could find about the shooter’s age according to Sting, but I’ve always felt that it was a young teen. Perhaps that stems from how reckless the boy was with the rifle. Why practice your aim on a human if you know the potential consequences? Shoot a can instead.

In the years since its initial release, “I Hung My Head” has been covered by both Johnny Cash and Bruce Springsteen. In fact, if you perform a Google search for the track’s title, it’s Cash’s version that appears first and foremost. That may have something to do with Cash’s legendary status—not to take anything away from Sting. It could also result from the fact that many prefer Cash’s version, as the western theme seems to fit with Cash’s role as arguably county music’s first “outlaw.”

Johnny Cash sits with an acoustic guitar in a still from the 1967 film The Road To Nashville, directed by Will Zens. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Johnny Cash sits with an acoustic guitar in a still from the 1967 film The Road To Nashville, directed by Will Zens. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Children and criminal liability

Remember, we are operating on the premise that the shooter in “I Hung My Head” is a boy instead of a man. I know I’ll receive at least a few emails arguing this point, but I firmly believe this song leaves his age up to interpretation—it’s different than a situation like Skid Row’s awesome hair metal hit “18 and Life.” We’ve got numbers to work with there. We don’t with “I Hung My Head,” so let’s roll with what we have.

With that settled, how does the law treat a juvenile (someone under 18) accused of murder? Maybe the best place to start is to differentiate the actual criminal liability we are discussing. Would this fact pattern constitute murder or a less severe form of homicide?

First-degree murder requires the prosecution to prove malice aforethought. Basically, they must prove an intentional killing—the “planning” or premeditation aspect. Second-degree murder on the other hand is still a deliberate act, but it doesn’t carry the same “planning” aspect. That form of homicide is usually akin to an act committed in the heat of passion.

Manslaughter, however, is reserved for situations where the killing was not intentional, and there was no planning—it usually applies in cases where the death was the result of an accident or some other standard that falls below intent. In the same vein, some jurisdictions also have a negligent homicide charge, which covers situations where someone perhaps hit an individual with a vehicle and killed them. Other jurisdictions also deal with felony murder, which occurs when an individual dies during the commission of a felony.

The facts presented in Sting’s song most likely equate to a manslaughter charge. While the boy intended to point the gun at another human, thus creating an inherently deadly situation, it’s clear from his surprise and the further realization that he did not mean to shoot the rider. At the end of the day, that may be a fact question for a jury to consider, but it seems to be the correct conclusion.

So, what about culpability? At common law, the “rule of sevens” was applied to determine criminal and tort liability for children. Children under 7 were not considered accountable for their criminal or tortious acts. Furthermore, there was a rebuttable presumption that children aged 7 to 14 lacked the capacity to be held liable. Conversely, there was a rebuttable presumption that children/adults aged 14 to 21 did have the capacity to be held responsible for their actions.

As the song seems to be set in a Wild West era, we can use common law theories to decipher the situation. The boy was most likely at least between the ages of 7 and 14, if not a bit older. There would have likely been arguments in favor of manslaughter as opposed to murder and regarding his capacity to be held liable for his actions. As the song ends with him awaiting execution, though, we can assume the court found he had the capacity to be held liable for the charge of murder, most likely.

Defending children in an adult system

Luckily, in today’s day and age, children can no longer be executed for their crimes. Ever since the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Roper v. Simmons (2005), imposing the death penalty on juveniles under 18 has been unconstitutional. The high court’s decision overruled the prior precedent set by Stanford v. Kentucky, which upheld the execution of offenders at or above the age of 16.

But exclusion from capital punishment doesn’t mean offenders under 18 get a free pass. Juveniles convicted of murder can still be sentenced to life without the possibility of parole and not for any other crime of conviction. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Graham v. Florida, juveniles convicted of any offense other than homicide cannot receive that punishment.

Yet many young offenders convicted of serious crimes don’t receive the benefit of processing their cases entirely through the juvenile court system. A number of jurisdictions, including my home state of Oklahoma, have “youthful offender” laws on the books that remove specific criminal allegations from the juvenile system to the adult arena based on the charge and the age of the accused.

Consequently, minors are also subjected to the full force of an adult criminal system when charged as a youthful offender and then certified for adult punishment. Those situations can easily end in minors serving lengthy prison sentences. Moreover, there are various intricacies and potential pitfalls involved in navigating a sometimes-confusing system, and it takes a pilot with experience to ensure the plane doesn’t crash and burn.

But that shouldn’t surprise anyone. Anytime we deal with a juvenile facing severe consequences, the stakes are raised, and the attention to detail must be heightened. There is too much to lose when looking at potential lost youth.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.