John Lennon’s lawyer turns paperback writer to recount little-known case

Author and lawyer Jay Bergen. Photo by Paul Mehaffey.

In March 1975, Jay Bergen stepped off an elevator on the seventh floor of the Dakota, New York City’s famed luxury co-op on the Upper West Side. He was met by a young man who escorted him into an apartment. Bergen was in John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s living room. A white Steinway grand piano sat across the space. The view of Central Park was spectacular.

A few minutes later, Ono entered, and the two introduced themselves. For the next hour, Bergen tells me, he was “politely grilled” by the former Beatle’s wife.

Bergen’s partner at Marshall, Bratter, Greene, Allison & Tucker was Lennon’s counsel in the dissolution of the Beatles. Bergen recently had been tapped to represent the musician in unrelated breach of contract litigation.

It was an “audition,” Bergen recalls of his meeting with Ono. She wanted to be sure he was the right lawyer to handle the case. “If she didn’t like me,” he explains, “I would have been out.”

Bergen passed the test, and for the next two years had a ticket to ride as Lennon’s lawyer in the matter. The representation included a lengthy bench trial in the Southern District of New York and culminated with a published opinion from the New York City-based 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

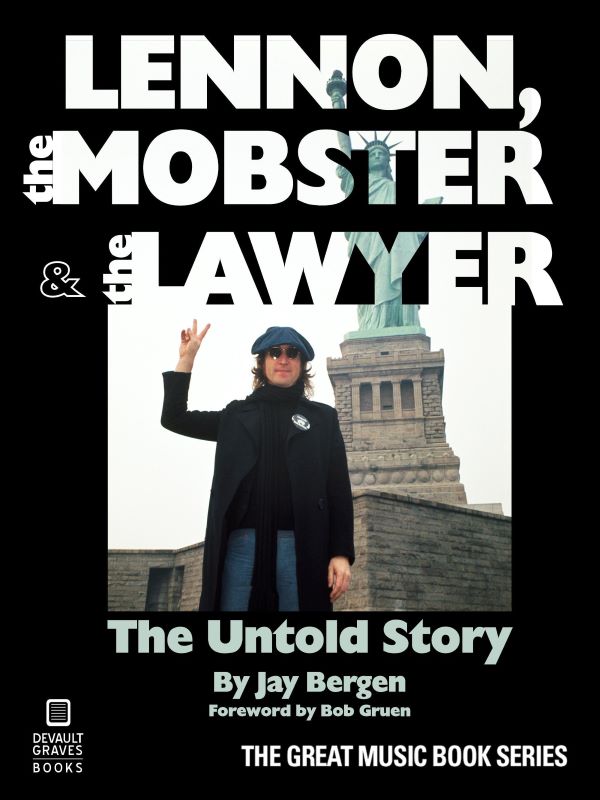

Lennon and Bergen parted ways after that, and Bergen went on to a long career as a litigator for various Manhattan firms. He retired in 2008. While his representation of Lennon always made for a good story, last month the Long Island native shared the case on a grander scale. He published Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer—The Untold Story, which recounts his representation of Lennon in this little-known case.

In a phone interview from his home in Saluda, which is in southwestern North Carolina, Bergen, 84, discussed his five-year effort as a paperback writer to share Lennon’s story.

Copyright kerfuffle

Lennon’s troubles began in 1973, after his settlement of a case alleging that his song “Come Together” had infringed the copyright in four words of Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me.” The rights to the song were the property of Big Seven Music Corp., a publishing company owned by Morris Levy, a music industry executive with alleged Mafia ties. For Levy, the situation wasn’t so Johnny be good, and he sued Lennon.

In resolving the copyright claim, Lennon agreed to include a trio of Big Seven-owned songs in a compilation album that he was making in which he performed rock ‘n’ roll hits from the 1950s. Levy was to receive certain royalties. Lennon shared a work-in-progress copy of the record with Levy. Despite it being a demo—a so-called rough mix—that was not yet record-release quality, Levy proceeded to sell it through television ads with mail-order fulfillment.

With the bootleg now out on the street, Lennon was forced to quickly finish and release the LP that he called Rock ‘N’ Roll. Lennon’s record company sent stern warnings to television stations that they were advertising an unauthorized album. Levy stopped selling Roots: John Lennon Sings the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hits and sued Lennon for breach of contract. At the heart of the litigation was who had the right to distribute the compilation album.

Bergen’s work is a mix of litigation play-by-play—including excerpts from the 5,000-page trial transcript—and anecdotes of his many encounters with Lennon that led to a close personal relationship between the two.

Bergen describes himself as a “big Beatles fan,” including seeing the Fab Four when they appeared at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens in 1964. Lennon was also one of the most famous people in America at the time. Surely there were challenges to having a client of this sort.

“Once I got over the shock of John Lennon walking into the conference room and sitting there and talking to me,” Bergen says, recalling their initial meeting, “it evolved that he was a client. And I treated him just like every other client that I’d ever had.”

A cool client

Bergen has much to say about the devotion that Lennon gave to the case. “John was really determined not to let Morris bully him,” Bergen tells me, explaining the reason behind his client’s intense interest in the matter. “I think he realized that he had made a mistake when he settled the ‘Come Together’ case. He’d now gotten into Morris’s clutches, and I think he decided ‘I’m not going to settle this case. We’re really going to be involved.’”

“John and Yoko were [in the courtroom] every day,” Bergen says of the weeks-long trial before Judge Thomas Griesa.

Bergen also calls Lennon “the best witness I ever represented or put on the stand in my 45-year career.” He describes Lennon as “very comfortable on the witness stand,” adding “I don’t think he was even slightly nervous.”

“I can’t think of one mistake he made,” Bergen recounts. “Witnesses get nervous. They start volunteering. We went over that. John did not volunteer. If he was asked a question, either on direct or cross examination, he answered the question. And that was it.”

Judging with an ear for music

Bergen gives credit for part of his success in the case—no contract found to exist between Lennon and Levy (affirmed on appeal); Lennon awarded contract damages on his counterclaim (reduced on appeal)—to Judge Griesa being a musician who played the piano and harpsichord in a classical music group.

Lennon also sought damages from Levy for injury to his reputation caused by the release of the shoddy Roots album. As a musician, according to Bergen, the judge had a trained ear and appreciation for Lennon’s creative process—which he testified to in detail.

After an open court playing of Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame”—both the Roots and Rock ‘N’ Roll versions—the judge drew the following conclusion:

“I don’t think there is any comparison. The Rock ‘N’ Roll is so much clearer; the voice was very poor and indistinct on Roots, it was almost hidden there. I could not tell it was John Lennon singing or anybody singing; it was a voice. The elements, whatever they are, were all fuzzed up in Roots, and I don’t know whether you call it surface noise or what kind of noise, but it was fuzzy, and I would not get anything much out of it. Now, the Rock ‘N’ Roll, it seems to me, the voice was clear and distinct, and every other element was distinct.”

In later awarding Lennon $35,000 for damage to his reputation (affirmed on appeal), the court observed that “Lennon has attempted a variety of ventures both in popular music and avant-garde music. Lennon’s product tends to be somewhat more intellectual than the product of other artists. What this means in my view is that Lennon’s reputation and his standing are a delicate matter and that any unlawful interference with Lennon in the way that Levy and the Roots album accomplished must be taken seriously.”

On Dec. 8, 1980, Lennon was killed by a gunman outside the Dakota. Early the next morning, Bergen headed to the scene of the tragedy. “I passed places where John and I had walked together,” Bergen says. “I didn’t linger to reminisce. I felt an urgency to be where John had last spoken, breathed, laughed, where he had most recently been alive.”

Bergen’s work comes nearly a half-century since he put Lennon’s creative process on display in a lower Manhattan courtroom. The numerous bankers’ boxes of the file could have stayed buried in the lawyer’s garage. But Bergen just couldn’t let it be.

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.