A look at Netflix's 'Longmire,' Indian Country and the battle for jurisdiction

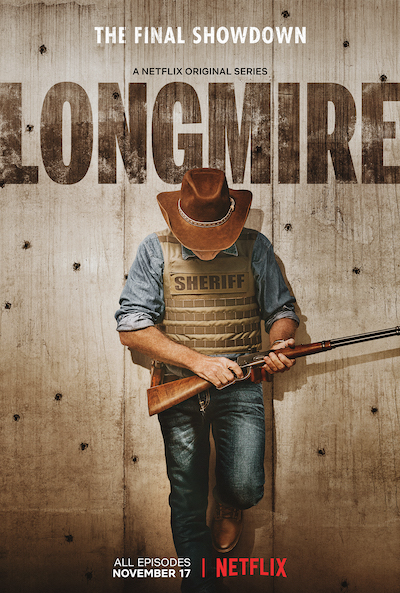

Robert Taylor and Lou Diamond Phillip in Longmire. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Being born and reared in western Oklahoma, I was always fairly familiar with the tribes in that area. Even though I don’t have any American Indian blood, plenty of my friends do, and I have had the opportunity to grow up experiencing the wealth of history and culture they offer.

Still, it wasn’t until law school that I began to understand the much further-reaching implications of the tribes’ historical clashes with the U.S. government. I had no idea that specific issues regarding jurisdiction were attributed to the tribe’s sovereignty. To be completely honest, I didn’t even realize the full extent of that issue until certain jurisdictional disputes recently arose in my home state of Oklahoma.

The McGirt decision

The most recent jurisdictional fight started with Patrick Dwayne Murphy. Murphy was convicted in Oklahoma state court for murder in the first degree and sentenced to death in 2000. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals upheld the conviction. Murphy subsequently appealed his conviction and sentence all the way to the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Denver alleging that since he is an American Indian and his alleged crimes occurred in Indian Country, he should have been charged and tried in federal court.

The 10th Circuit agreed with Murphy, reversed his conviction and sentence, and remanded with instructions. He appealed the case to the Supreme Court of the United States, where it sat idle for some time.

That is, until Jimcy McGirt’s appeal finally made its way to our nation’s highest court in 2019. McGirt was convicted of various sex crimes. He, too, was denied any relief by OCCA. Ultimately, SCOTUS granted certiorari to decide much the same issue as Murphy presented: whether the state of Oklahoma has jurisdiction to prosecute an American Indian who commits a crime in Indian Country.

In an opinion authored by Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, the high court ruled that Oklahoma state court’s do not have jurisdiction to prosecute American Indians (McGirt is an enrolled member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma) for major crimes that occurred in Indian Country pursuant to the federal Major Crimes Act, and the Muskogee Creek Reservation is considered Indian Country under federal law.

As such, SCOTUS reversed the ruling of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals. Now the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Oklahoma has the option of retrying McGirt’s case in federal court.

Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Tribal jurisdiction in pop culture

Only a few television shows in recent memory really touch on the battle between states and tribes over criminal jurisdiction. Longmire originally aired on A&E from 2012 to 2014.

The show was then picked up by Netflix, which aired new episodes from 2015 to 2017. Longmire followed the exploits of Walt Longmire (played by Robert Taylor), the sheriff of fictional Absaroka County, Wyoming. The television series was based on the Walt Longmire Mysteries book series written by Craig Johnson.

The titular character was tasked with the often unenviable job of navigating the rules and restrictions that come with competing claims of jurisdiction. Longmire does his best to enforce the law. Still, a central focus of the series showed the difficulty of trying to weave his obligated authority into that of the local American Indian reservation and the reservation’s tribal police force.

Luckily for Longmire, his friend Henry Standing Bear (played by Lou Diamond Phillips) is a member of the Cheyenne tribe and available to help deal with tribal police and traverse the aspects of Native American life that are out of Longmire’s wheelhouse.

Although Longmire is no longer in production, TNT’s Yellowstone is still pumping out new episodes. The series first aired in 2018 and follows the Dutton family, starring Kevin Costner as the patriarch, as it operates the ranch in the face of constant confrontation. Part of the conflict comes from the fact that the ranch borders an American Indian reservation.

While the series does not share the same law enforcement focus as Longmire, the setting and the location lend themselves to portraying plenty of issues that arise when land borders and jurisdiction come into play.

Implications for tribes and local law enforcement

As both series strive to show, jurisdictional issues often arise between various entities over tribal land and reservations. As the McGirt case makes clear, though, those issues can have a much longer-lasting effect than simply which agency gets to investigate and make the arrest.

Currently, I find myself fighting these issues in state district court and in front of the OCCA. My contention, along with every other criminal defense attorney I have discussed the matter with, is that the McGirt ruling applies to any and every allotment of land that qualifies as Indian Country under federal law. Even though McGirt was explicitly limited to the Muskogee Creek reservation, the legal reasoning is applicable to land given to a federally recognized tribe via treaty with the United States, which has not been disestablished by Congress.

Consequently, along with many other defense attorneys, I am filing motions to dismiss in criminal cases where I believe the state of Oklahoma lacks subject matter jurisdiction over the matter in light of McGirt.

While I will have to likely wait some time to see how the OCCA will ultimately decide these issues, I have heard numerous stories from colleagues concerning the varying reception of our attempts to (rightfully) extend McGirt to other reservations. Some judges agree, and others are doing their best to concoct procedural hurdles and bars to applying the decision.

Even with some motions to dismiss that are being litigated in what SCOTUS has clearly held as Indian Country (the Muskogee Creek reservation), it’s my understanding that judges and prosecutors argue certain documentation, such as tribal membership cards and Certificates of Degree of Indian Blood, aren’t sufficient in and of themselves to establish a defendant as an American Indian.

Moreover, as I understand it, some judges are requiring defense counsel to go to extraordinary lengths to establish that a crime allegedly occurred in Indian Country, even if the arresting officer’s sworn affidavit states so. I understand the desire to get it right. As a practicing attorney, I know there are rules of evidence that have to be followed. But I also know that stipulations are easy to agree to if there is no genuine question of fact, and a judge’s ability to take judicial notice is available for a reason.

Consequently, it’s hard for me not to believe that some counties and jurisdictions wish to hold onto as many criminal cases as possible until and unless they are literally forced to relinquish them on a writ or appeal. Why would that be the case? Money. Counties in Oklahoma get an extraordinarily large sum from the people they prosecute.

Aside from court costs and the costs of incarceration they can saddle a defendant with indefinitely, the individual district attorney’s offices literally get reimbursed up to $960.00 per defendant “for the costs incurred during the prosecution of the offender.”

When I was young, a wise person once told me that you can find the root of almost any issue if you follow the money. Maybe it’s the cynic in me, but I think that might be the case in this situation, as well.

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.